Latest News

-

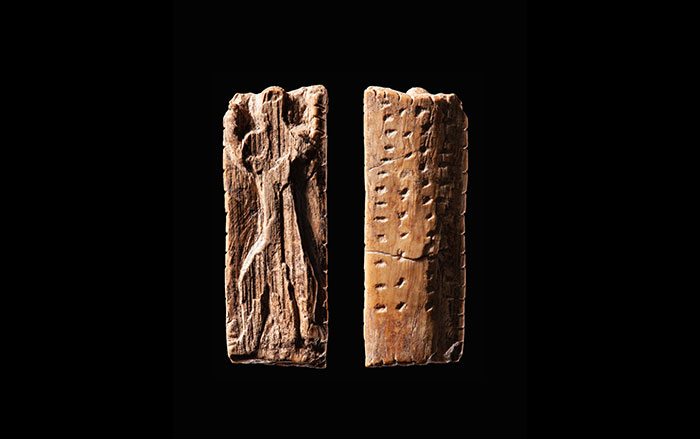

© Landesmuseum Württemberg/Hendrik Zwietasch, CC BY 4.0

© Landesmuseum Württemberg/Hendrik Zwietasch, CC BY 4.0 -

News February 27, 2026

Study Pushes Back Occupation of Southern Argentina Site by 500 Years

Read Article Gustavo Martínez

Gustavo Martínez -

Swansea Council

Swansea Council -

Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

-

Barry Molloy

Barry Molloy -

News February 25, 2026

Dating of Early Human Site in Jordan Valley Pushed Back by 300,000 Years

Read Article

-

-

Panama's Ministry of Culture

Panama's Ministry of Culture -

Courtesy Robby Vervoort

Courtesy Robby Vervoort -

Elizabeth Paris

Elizabeth Paris -

News February 23, 2026

Singapore's First Ancient Shipwreck Reveals Cargo of Yuan Dynasty Porcelain

Read Article

-

Utah State Historic Preservation Office

Utah State Historic Preservation Office -

Government of Wuhan

Government of Wuhan -

University of Aberdeen

University of Aberdeen -

Supreme Council of Antiquities

Supreme Council of Antiquities -

Skyview

Skyview

Loading...