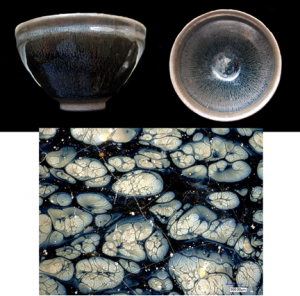

BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA—Catherine Dejoie of Lawrence Berkeley National Lab and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology led an international team of scientists in the analysis of the chemical composition of Jian bowls, made some 1,000 years ago in China’s Fujian Province. The bowls, which are known for retaining heat and for their patterned glaze, were made from local iron-rich clay and coated with a mixture of clay, limestone, and wooden ash. When the bowls were fired, the clay hardened, the coating melted, and oxygen within the glaze pushed iron ions to the surface. As the glaze cooled, molten iron flux flowed down the sides of the bowls and crystallized into iron oxides, forming the bowls’ characteristic patterns. X-ray diffraction, electron microscopy, and other techniques revealed that rare epsilon-phase iron oxide was formed on the bowls in two of the three patterns. This type of iron oxide is highly valued for its persistent magnetization, high resistance to corrosion, and lack of toxicity, but it is difficult to create with modern equipment. “The next step will be to understand how it is possible to reproduce the quality of epsilon-phase iron oxide with modern technology,’ Dejoie announced at the Berkeley Lab.

BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA—Catherine Dejoie of Lawrence Berkeley National Lab and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology led an international team of scientists in the analysis of the chemical composition of Jian bowls, made some 1,000 years ago in China’s Fujian Province. The bowls, which are known for retaining heat and for their patterned glaze, were made from local iron-rich clay and coated with a mixture of clay, limestone, and wooden ash. When the bowls were fired, the clay hardened, the coating melted, and oxygen within the glaze pushed iron ions to the surface. As the glaze cooled, molten iron flux flowed down the sides of the bowls and crystallized into iron oxides, forming the bowls’ characteristic patterns. X-ray diffraction, electron microscopy, and other techniques revealed that rare epsilon-phase iron oxide was formed on the bowls in two of the three patterns. This type of iron oxide is highly valued for its persistent magnetization, high resistance to corrosion, and lack of toxicity, but it is difficult to create with modern equipment. “The next step will be to understand how it is possible to reproduce the quality of epsilon-phase iron oxide with modern technology,’ Dejoie announced at the Berkeley Lab.