Cuneiform

Maps

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Cuneiform tablets were long used for making maps and plans of towns, rural areas, and houses, but rarely for anything larger or without commercial interest. A unique tablet, thought to have come from Sippar in present-day Iraq and dating to around the sixth century B.C., shows much more and reflects something of how ancient Babylonians saw themselves in the world. This Mesopotamian mappa mundi consists of a circular map surrounded by triangles, with explanatory text above and on the opposite face. The central circle shows the Babylonian realm, bisected by the Euphrates, which is straddled by Babylon itself. Several other geographical areas are labeled by name, and the continent is surrounded by a ring called the “ocean” or “Bitter River.” Beyond the boundary waters are seven or eight outlying regions or islands represented by triangles, of which portions of four survive. The text is largely concerned with these far-flung, perhaps mythological, places. One is described as a “place where the sun is not seen,” another as a place where “a winged bird cannot safely complete its journey.” Further descriptions speak of “ruined” cities and gods, and animals both fantastic (great sea-serpent, scorpion-man) and exotic (lion, monkey, chameleon).

Cuneiform tablets were long used for making maps and plans of towns, rural areas, and houses, but rarely for anything larger or without commercial interest. A unique tablet, thought to have come from Sippar in present-day Iraq and dating to around the sixth century B.C., shows much more and reflects something of how ancient Babylonians saw themselves in the world. This Mesopotamian mappa mundi consists of a circular map surrounded by triangles, with explanatory text above and on the opposite face. The central circle shows the Babylonian realm, bisected by the Euphrates, which is straddled by Babylon itself. Several other geographical areas are labeled by name, and the continent is surrounded by a ring called the “ocean” or “Bitter River.” Beyond the boundary waters are seven or eight outlying regions or islands represented by triangles, of which portions of four survive. The text is largely concerned with these far-flung, perhaps mythological, places. One is described as a “place where the sun is not seen,” another as a place where “a winged bird cannot safely complete its journey.” Further descriptions speak of “ruined” cities and gods, and animals both fantastic (great sea-serpent, scorpion-man) and exotic (lion, monkey, chameleon).

According to Wayne Horowitz of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the tablet “reflects a general interest with distant areas during the first half of the first millennium, when the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires reached their greatest extents.”

Laws

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

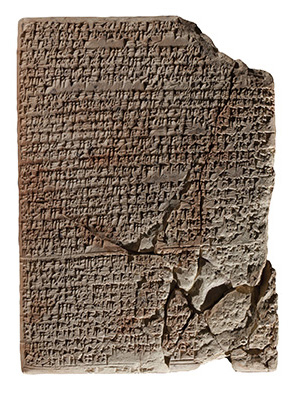

The best known and most influential of the Mesopotamian law codes was that of King Hammurabi of Babylonia (r. 1792–1750 B.C.). Featuring nearly 300 provisions covering topics ranging from marriage and inheritance to theft and murder, it is the most comprehensive of these codes. While it famously includes retributive, eye-for-an-eye clauses, it also takes on more complex scenarios, imposing harsh punishments for accusation without proof and for errors made by judges.

The best known and most influential of the Mesopotamian law codes was that of King Hammurabi of Babylonia (r. 1792–1750 B.C.). Featuring nearly 300 provisions covering topics ranging from marriage and inheritance to theft and murder, it is the most comprehensive of these codes. While it famously includes retributive, eye-for-an-eye clauses, it also takes on more complex scenarios, imposing harsh punishments for accusation without proof and for errors made by judges.

The code appears written in intentionally archaic cuneiform on a towering seven-and-a-half-foot-tall diorite stela that was recovered from Susa, in present-day Iran, where it was taken after being stolen in the twelfth century B.C. Featuring a relief of Hammurabi receiving divine sanction from the sun-god Shamash in its upper portion, this stela and others like it would have been publicly displayed during Hammurabi’s reign and long after. “The code was certainly set up in in city squares, in temple courtyards, in public places—where it was seen by populations,” says Martha Roth, an Assyriologist at the University of Chicago. It was also used in the training of scribes for at least 1,000 years after its composition, and several manuscripts of it were found in King Ashurbanipal’s (r. 668–627 B.C.) seventh-century B.C. library at Nineveh, in present-day Iraq.

The precise legal function of Hammurabi’s code is unclear, as there are few references to it in legal records from his era. However, says Roth, these records do suggest that “the provisions as outlined in Hammurabi map onto the daily reality in a fairly close way.” The code was also clearly intended to establish Hammurabi as the guarantor of justice for his people. “In order that the mighty not wrong the weak, to provide just ways for the waif and the widow,” reads its epilogue, “I have inscribed my precious pronouncements upon my stela.”

This trope of the king as protector of the downtrodden appears regularly in Mesopotamian inscriptions, but the earliest known example is found on several cone tablets known as the reforms of Urukagina (r. ca. 2350 B.C.), a king of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present-day Iraq. According to the inscriptions, the king addressed a number of social inequities, including reducing the power of greedy temple overseers and abusive foremen. “There’s a consciousness about reform in it that is unique until now,” says Roth, “and in history it comes about here for the first time.”

Letters

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Among the thousands of Mesopotamian tablets containing both official and personal letters, one example stands out as the first recorded customer complaint and evidence of a business relationship gone very sour. Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Nanni expressed his extreme displeasure to the merchant Ea-nasir about a recent copper shipment:

Among the thousands of Mesopotamian tablets containing both official and personal letters, one example stands out as the first recorded customer complaint and evidence of a business relationship gone very sour. Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Nanni expressed his extreme displeasure to the merchant Ea-nasir about a recent copper shipment:

When you came, you said to me as follows: “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots that were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: “If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!” What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt....Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.

Recipes

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

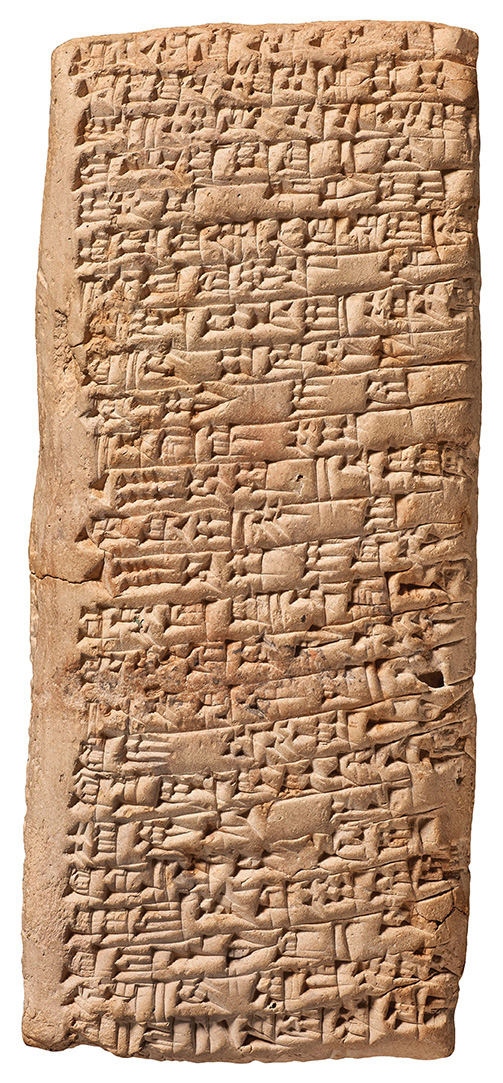

The earliest known recipes, by many centuries, are found on three tablets dating to the Old Babylonian period. Though seemingly simple, their minimal instructions could only have been followed by experienced chefs working for the highest echelons of society. This particular tablet features 25 recipes for stews and soups, both meat and vegetarian, including some directions—though no measurements or cooking times—for an amursanu-pigeon stew:

The earliest known recipes, by many centuries, are found on three tablets dating to the Old Babylonian period. Though seemingly simple, their minimal instructions could only have been followed by experienced chefs working for the highest echelons of society. This particular tablet features 25 recipes for stews and soups, both meat and vegetarian, including some directions—though no measurements or cooking times—for an amursanu-pigeon stew:

Split the pigeon in half—add other meat.

Prepare the water, add fat and salt to taste;

Breadcrumbs, onion, samidu, leeks, and garlic

(first soak the herbs in milk).

When it is cooked, it is ready to serve.

With the exception of amursanu, which is probably a type of pigeon, and samidu, an unknown spice, the ingredients are certainly recognizable. But the dish would, in fact, be impossible to replicate, says Benjamin Foster, curator of the Yale Babylonian Collection. “People often think that because they can cook Arab or Persian food that they can make this stuff, but they don’t know how much regional cooking was changed by the Muslim conquests. If you cook these up using modern Near Eastern ingredients, it is pure fantasy—but often delicious.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement