Romans on the Bay of Naples

A spectacular villa under Positano sees the light

September/October 2016

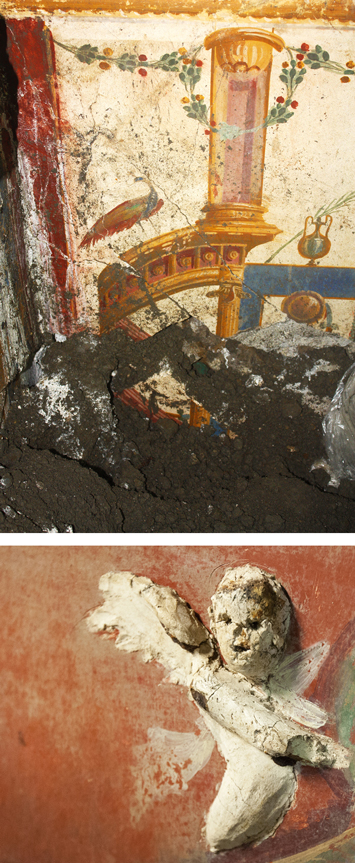

Once we reach the spot, you won’t believe your eyes,” says archaeologist Luciana Jacobelli of the University of Molise as she opens a small door to the crypt of the church of Santa Maria Assunta in the center of town. It’s very dim inside, and she has to use a flashlight as we make our way. We slowly climb down a series of ladders through a forest of iron scaffolding toward what seems to be the only well-lit area, nearly 30 feet under the church. Jacobelli then leads me into a room and, as promised, frescoes in dazzling green, yellow, red, and blue seem to illuminate the space on their own. We have arrived at the extraordinarily well-preserved remains of a lavish villa marittima, or seaside villa, once a luxurious retreat for the rich of ancient Rome to escape the summer heat and the hustle and bustle of city life in the first centuries B.C. and A.D.

Swiss architect and engineer Karl Weber, the first scholar to supervise excavations of the areas destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, appears to have seen the villa on April 16, 1758, during his explorations. In his field report he writes that he had begun to dig near the “church with bell tower, not far from the beach that is at the base of Mount Santa Maria a Castelli and Mount Sant’Angelo; at a depth of 30 spans we found a famous ancient building whose first mosaic is made of white and fine marble.”

Swiss architect and engineer Karl Weber, the first scholar to supervise excavations of the areas destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, appears to have seen the villa on April 16, 1758, during his explorations. In his field report he writes that he had begun to dig near the “church with bell tower, not far from the beach that is at the base of Mount Santa Maria a Castelli and Mount Sant’Angelo; at a depth of 30 spans we found a famous ancient building whose first mosaic is made of white and fine marble.”

It was only during restoration work on the crypt in 2003 that archaeologists had a chance to enter the villa’s stunning triclinium, or dining room, for the first time. But after only three years of digging, they were forced to stop when funding ran out, and it wasn’t until the summer of 2015 that excavations resumed. For the rest of the year, before funding for the project ran out again, Jacobelli led a rescue excavation under the supervision of the local archaeological superintendent, Adele Campanelli, and archaeological supervisor Maria Antonietta Iannelli. A team of archaeologists and conservators worked to remove mud and lapilli (small stones ejected by a volcanic eruption) and to expose and clean the stunning wall paintings emerging from the debris.

|

Slideshow:

|

Roman Holiday

|

Thanks to an ancient system of artificial terraces cut into the hillside on which Positano sits, the villa may have sprawled across more than 2.25 acres. Some scholars think that it might even have been as large as the town of Positano. Mantha Zarmakoupi of the University of Birmingham, an expert on the ancient Roman luxury villas of the Bay of Naples, disagrees. “I can imagine that the villa was perched on a terraced platform with ramps leading to other terraces below, and may have stretched over two or more levels in the hillside, as houses do today, but I don’t think that it would have occupied the entire village,” she says.What isn’t in doubt, however, is the excellence of the frescoes covering the villa’s walls. “The quality of the wall paintings is very high, and the triclinium’s decorative program seems unique,” says Zarmakoupi. “The combination of frescoes with stucco is rare and remarkable. The rendering of details in stucco, for example in the figures both holding and decorating the drapery, accentuates the feeling that the cloth is actually pliable.”

Thanks to an ancient system of artificial terraces cut into the hillside on which Positano sits, the villa may have sprawled across more than 2.25 acres. Some scholars think that it might even have been as large as the town of Positano. Mantha Zarmakoupi of the University of Birmingham, an expert on the ancient Roman luxury villas of the Bay of Naples, disagrees. “I can imagine that the villa was perched on a terraced platform with ramps leading to other terraces below, and may have stretched over two or more levels in the hillside, as houses do today, but I don’t think that it would have occupied the entire village,” she says.What isn’t in doubt, however, is the excellence of the frescoes covering the villa’s walls. “The quality of the wall paintings is very high, and the triclinium’s decorative program seems unique,” says Zarmakoupi. “The combination of frescoes with stucco is rare and remarkable. The rendering of details in stucco, for example in the figures both holding and decorating the drapery, accentuates the feeling that the cloth is actually pliable.”