The Frankish Settlements

November/December 2018

Among the warriors and pilgrims who arrived in the Middle East during the Crusades were European immigrants eager to begin a new life in a new land. Historians have long assumed that the vast majority of these people, typically called Franks though not all were French, huddled in well-protected towns and avoided the potentially dangerous countryside. Five previously excavated but newly reexamined Crusader-era settlements, all located just north of Jerusalem, are now beginning to reveal how these Europeans made their homes in rural areas as well. These towns have long puzzled archaeologists, who in recent decades have exposed twelfth-century homes built of sturdy stone walls, some more than six feet thick, packed together along a central road facing the street. This layout is unusual in the Near East, where central courtyards are the norm, and homes are rarely built against one another except in cities. The structures often had two stories and barrel-vaulted ceilings, rather than the one-story buildings with domed or flat roofs typical of the region.

Among the warriors and pilgrims who arrived in the Middle East during the Crusades were European immigrants eager to begin a new life in a new land. Historians have long assumed that the vast majority of these people, typically called Franks though not all were French, huddled in well-protected towns and avoided the potentially dangerous countryside. Five previously excavated but newly reexamined Crusader-era settlements, all located just north of Jerusalem, are now beginning to reveal how these Europeans made their homes in rural areas as well. These towns have long puzzled archaeologists, who in recent decades have exposed twelfth-century homes built of sturdy stone walls, some more than six feet thick, packed together along a central road facing the street. This layout is unusual in the Near East, where central courtyards are the norm, and homes are rarely built against one another except in cities. The structures often had two stories and barrel-vaulted ceilings, rather than the one-story buildings with domed or flat roofs typical of the region.

Since the 1940s when these small towns were first excavated, archaeologists theorized that they were built during the twelfth century when the Crusaders were at their peak of power and a measure of peace prevailed around Jerusalem. But archaeologist Elisabeth Yehuda of Tel Aviv University noticed that the buildings were themselves designed as miniature forts, with second stories accessible only by way of a narrow staircase or removable ladder, and therefore easy to defend from attack. She argues that the second stories were, in effect, temporary refuges in times of trouble.

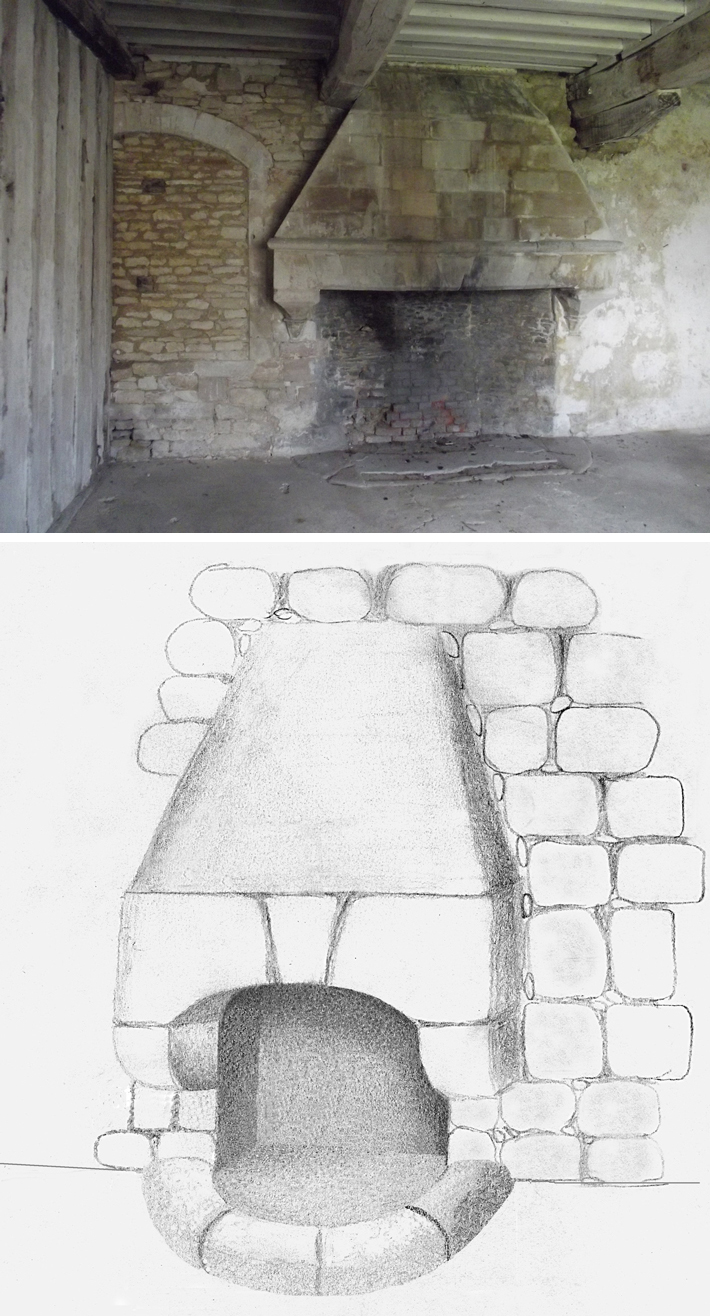

While conducting research in European archives, Yehuda found examples of stone houses of similar design in urban Europe also dating to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Though not quite as fort-like as the Crusader structures, they reflected the growing prosperity of artisans and merchants through their sturdy construction and careful attention to detail. She then focused on the decorative corbelled fireplaces in the main room on the first floor of many of the Frankish dwellings. These are unique in the Middle East, and she discovered they matched those of some well-to-do homes of the era in France and Germany. Used for heating and cooking, they signaled the wealth and sophistication of the owner at a time when open fireplaces were the rule. “They were showpieces,” Yehuda says. “It was the first thing you would see when you walked in the door.” Excavations also showed that residents of the settlements dined on fine tableware imported from around the Mediterranean.

While conducting research in European archives, Yehuda found examples of stone houses of similar design in urban Europe also dating to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Though not quite as fort-like as the Crusader structures, they reflected the growing prosperity of artisans and merchants through their sturdy construction and careful attention to detail. She then focused on the decorative corbelled fireplaces in the main room on the first floor of many of the Frankish dwellings. These are unique in the Middle East, and she discovered they matched those of some well-to-do homes of the era in France and Germany. Used for heating and cooking, they signaled the wealth and sophistication of the owner at a time when open fireplaces were the rule. “They were showpieces,” Yehuda says. “It was the first thing you would see when you walked in the door.” Excavations also showed that residents of the settlements dined on fine tableware imported from around the Mediterranean.

The inhabitants of the Frankish settlements were neither peasants nor knights, says Yehuda, but skilled artisans and traders who intended to make this new land their permanent home. They also planned to maintain their European identity. “The settlers didn’t fuse with the local environment. They flouted their otherness in remarkable ways such as building in stone to say that they were here to stay,” she adds. They made a conscious choice to live in the countryside rather than living in the Crusader cities notorious for crowding and disease.

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The American Canine Family Tree

Off the Grid

Mars Explored

Aztec Fishing

Iron Age Teenagers

Hand of God

Beauty Endures

Let Them Eat Soup

Another Form of Slavery

Eat More Spore

Well, Well

Nomadic Necropolis

Conan's Storm Cellar

World Roundup

Aztec rain temple, Ötzi’s last meal, Roman whalers, and Germany’s oldest public library

Artifact

A draft of comfort

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement