On a warm, windy day in the spring of 2022, archaeologist Michael Malliaris unlocks the gate in the construction fence that surrounds the most recently uncovered evidence of Berlin’s past. Inside is a broad expanse of light brown soil the size of a football field, dotted with deep pits revealing stone and brick walls and floors dating back nearly 800 years. Across the street is an imposing modern gray stone city administration building. On the other side of the excavation area, several lanes of traffic crawl past. A few red-and-white shipping containers inside the fence serve as Malliaris’ office and headquarters. Malliaris, at the time an archaeologist working for Berlin’s Monument Authority, is a 25-year veteran of rescue excavations. Trained as a classical archaeologist, he found himself caught up in the rush of digs that accompanied a building boom across the former East Germany after the fall of Communism there. But this is the biggest project he’s ever worked on. “It’s a singularly intense excavation,” Malliaris says.

This work promises to fill in major gaps in what historians know of Berlin’s origins. Perhaps surprisingly, given the city’s prominence, there remain numerous open questions. Devastating fires in the fourteenth century destroyed archives from the city’s first years, and between 1618 and 1648, Berlin lost half its population and many of its buildings to the violence of the Thirty Years’ War. In subsequent centuries, the city was conquered many times, including by Napoleon in 1806 and Stalin in 1945. “There are almost no written sources for the early years,” says Ines Garlisch, a local historian who specializes in Berlin’s medieval period. “That’s where archaeology comes into play.”

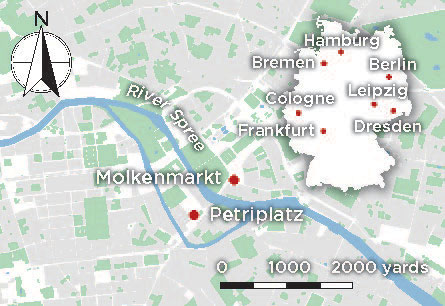

By 2028, the area under excavation, known as the Molkenmarkt, or Whey Market, perhaps because in its earliest incarnation it was dedicated to selling dairy products, will take shape as a new neighborhood. But first, the team of archaeologists led by Malliaris is investigating what’s left of the original Berlin. Over the past three years, the team has been digging year-round to excavate a section of ground near the Spree River. Not far away, another team has uncovered the foundations of an early medieval church and thousands of medieval graves. And just up the river, construction of a museum gave archaeologists the chance to investigate the site of a former Prussian palace, a royal residence whose history stretches back to the thirteenth century. Finds there include massive fans installed in the 1800s to remove soot from the palace’s coal-fired heating system. Still more discoveries, including sculptures labeled “degenerate” by the Nazis and thought to have been destroyed during the war, emerged during construction of a new subway line through a park across from the palace. And evidence of the city’s early industrialization was unearthed in the form of an electric plant built to power Berlin’s first electric lights. They also located a nineteenth-century Prussian art academy.

Visitors to Berlin often remark on how present its recent history is. The city is full of monuments celebrating triumphs of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Prussian emperors and memorials to victims of the Second World War. There are less traditional reminders of the recent past, too, including bullet holes in walls built before World War II, the line of bricks embedded in miles of streets marking the former course of the Berlin Wall, and the stark Soviet-era architecture built in the postwar period.

Yet very little is known about Berlin’s early days, including exactly when it was founded, or by whom. Even the origins of the city’s name are unclear: Berlin may be derived from Bär, German for “bear”—the animal is featured on the city’s coat of arms—or from a Slavic word for swamp. Unlike in many other German cities, there are few vestiges of Berlin’s earliest era—at least not aboveground. Even its original street plan was altered by war and by ambitious urban planners in the twentieth century, when winding medieval alleys were replaced by broad, car-centric streets and wide-open plazas. “If you want to understand anything about the city’s early history, you have to use archaeology,” says Matthias Wemhoff, Berlin’s city archaeologist and the director of the Museum for Pre- and Early History. “This is really a special chance.” Malliaris’ ongoing dig is the latest in an unprecedented series of archaeology projects in the heart of the city, all necessitated by a wave of urban renewal and investment that followed German reunification in 1990. “You won’t find any other cities in Germany with such a large area under construction,” says Wemhoff.

Pointing to a laminated map of the excavation area in the early 1930s—and plugging his ears briefly as ambulances howl past just a few dozen yards away—Malliaris explains that the current excavations are possible because of grandiose plans made in the Nazi era. The area has been densely populated for at least 800 years, and formed part of the city’s earliest core. Even after the construction of the so-called Red Town Hall, a redbrick edifice with a 300-foot-tall central tower, was completed in 1869, the streets nearby were home to thousands of people. Dozens of crowded apartment buildings were packed along narrow, twisting streets and alleys, most following the city’s original street plan. But at the turn of the twentieth century, planners had begun to tear down parts of the neighborhood and put up a city hall annex to house the growing ranks of bureaucrats. When Hitler came to power in the 1930s, authorities destroyed the rest of the neighborhood to make room for yet another mammoth administration building, part of a plan to completely reshape the German capital.

World War II broke out before construction of this administration building could begin. As the war dragged on, many of the area’s surviving buildings were badly damaged by bombs and urban combat. After the war, what was left of the city’s historic center ended up on the eastern side of the Berlin Wall, at the heart of East Berlin. In the 1980s, much of what remained was built over with prefabricated concrete apartment buildings as part of celebrations of the 750th anniversary of the city’s traditional founding date. On the other side of the Spree, towering Communist-era housing blocks covered still more of the early city. “So much was destroyed,” says Garlisch. “What the war didn’t manage to wipe out, the East German government did.”

The area around the Molkenmarkt was spared from the explosion of postwar construction. It remained an empty lot until East Berlin’s Communist government paved over most of it in the 1960s, sealing prewar ruins under a few feet of concrete and asphalt roadway. Until Malliaris’ team started their work, no one really knew what lay underneath, or what condition it was in. The very first test trenches showed that the busy road above had preserved the archaeology. Digging a few hundred square yards at a time, researchers remove artifacts for future study and map out medieval streets, basements, and foundations. Once they’ve dug down to the city’s earliest layers, below which lies sandy soil with no artifacts, they quickly move on to the next plot, making room for construction crews. Sometimes just a few weeks pass between the last finds coming out of the ground and road crews beginning work at a location. Traffic, meanwhile, must be routed around new excavation areas every few months.

Because the entire expanse belongs to the city of Berlin, it’s possible to excavate it all at once, rather than negotiating with individual landowners parcel by parcel. Typically, urban rescue excavations are conducted one new underground parking garage or basement at a time. To have access to more than eight acres at once is unique, Wemhoff explains, and will ultimately allow researchers to put together a more complete picture. “What’s really special is that we can dig one-fifth of the whole medieval city of Berlin,” he says. “That lets us say things about settlement patterns, architecture, social structure, and class in a very different way than most digs.”

The first mention of Berlin is in an account of a 1237 legal dispute that names a priest from the town of Cölln as a witness. Historians know from documents preserved in other towns in the region that the German capital began as two settlements, Berlin and Cölln, facing each other on opposite banks of the Spree. For centuries, 1237 was recognized as the city’s official beginning, although historians assumed it was probably at least a few decades older. “If a priest is named, you have to figure there’s a church,” Garlisch says, “so there was probably already a city twenty or thirty years before.” Connected by a bridge, the two towns had their own market squares, town halls, and churches, along with separate mayors and town councils. Some of the few surviving records from this early period show it wasn’t until 1432 that the two towns formally merged into a single city of about 8,500 residents.

At the time, the region was something of a frontier sandwiched between thickly settled German cities and duchies to the west and Slavic settlements to the east. Berlin’s location made it a waypoint for river trade from central Germany to ports on the Baltic Sea, and it was part of a trading league that included ports such as Stettin, Hamburg, and Bremen. A dam across the river probably forced merchants to offload cargo in Berlin before sailing farther, lining local pockets. Sometimes the dam failed, routing destructive floodwaters into the city. Leaning up against the wall in the team’s shipping container office is a striped panel, part of a 12-foot-deep profile archaeologists preserved by applying epoxy to the side of a deep trench before digging it out. “You can go through the layers and see 800 years of history,” Malliaris says, indicating a sandy layer atop a dark brown line. “I think there was a flood here, and they had to fill the spot with sand.”

Berlin remained a sleepy outpost for centuries, overshadowed by Cologne, Leipzig, and Dresden. It wasn’t until the late 1600s that things began to change, and the city’s later history is far better documented. Beginning in 1701, Berlin became the seat of the rapidly growing Prussian Empire, a militaristic German kingdom that rose to prominence in the mid-1700s. Prussian kings tangled with Napoleon, who defeated them and occupied the city. Prussia later recovered, and by the mid-1800s had united most of German-speaking Europe into a single country with Berlin as its capital.

As Prussia boomed, so did Berlin. Its population topped 100,000 by 1750 and was close to a million by 1850. On the eve of World War II, Berlin was one of Europe’s industrial centers, with a population of nearly five million. This history lies jumbled underneath the city’s modern center. As Malliaris and his team excavate the foundations of early houses, for example, they are finding ample evidence of how Berlin struggled to accommodate its growing numbers. In the Middle Ages, houses often had spacious inner courtyards with wells and room for animals. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, subterranean structures such as wells and storage cellars were filled in and built over to add housing. The medieval foundations, the team is finding, were often left in place.

More evidence of early Berlin was unearthed just a few hundred yards from the Molkenmarkt at a site known as the Petriplatz. There, between 2007 and 2010, Humboldt University archaeologist Claudia Melisch supervised the excavation of St. Peter’s Church, which was rebuilt five times after it was first constructed around 1200, most recently in the 1840s. The church was badly damaged by Allied bombs during World War II and torn down in the early 1960s. Melisch didn’t expect to find much in the soil around the church, especially since archival records showed that its cemetery had been closed in the late 1500s. In the subsequent centuries, the surrounding neighborhood was densely built over. But when she and her team started digging, they almost immediately began uncovering human bones. Ultimately, archaeologists identified 3,200 graves containing remains of more than 4,000 people. Melisch focused on the cemetery’s deepest graves, which she suspected belonged to some of the first people to be buried in what is now Berlin and was then Cölln. These early burials were simple, with no grave goods or coins to help date them. She turned to the bones themselves, using radiocarbon dating to determine when the people had died. The results were a surprise. The archaeological evidence from Petriplatz shows that the first known Berliners lived and died there around 1150, at a time when control of the region was still contested among competing Slavic and German princes. This timing suggests that the ruler of nearby Brandenburg was the city’s founder. “We need to rethink the city’s whole history,” says Garlisch, who worked with Melisch to analyze the Petriplatz finds.

Analysis of the skeletons has revealed key evidence of where these early Berliners came from. Chemical traces in their bones suggest they were migrants from other parts of Germany, including areas several hundred miles to the west, near modern-day Frankfurt and Fulda. One early theory was that the city was settled by a few families or clans seeking their fortune in a relatively unpopulated part of Germany. But in studying DNA samples from the remains, the researchers did not find any familial relationships among 50 of the men in the graves, suggesting a founding population of a few dozen unrelated craftsmen and merchants, perhaps with small families in tow. Melisch says the settlers were likely lured with the promise of tax breaks and free land from one of the local rulers competing for control over the region.

Early Berliners were remarkably healthy—and tall, with many of the men standing more than six feet and the women taller than the average German woman today. In subsequent centuries, skeletons from the cemetery show, people were shorter and more likely to die from disease. Researchers have found mass graves filled with children and young adults dating to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in the Petriplatz cemetery, suggesting that diseases such as plague, hepatitis B, and ringworm infections spread easily in the crowded city.

These finds have forced historians to push the city’s founding date back by almost a century. Combined with the ongoing digs across the river and down the street, they paint a very different picture of early Berlin. Rather than a loose collection of merchants and traders that eventually evolved into a city, it was a well-planned colonial outpost.

The Molkenmarkt excavations have drawn attention to Berlin’s history, with regular Friday-afternoon tours pulling in curious crowds. People are naturally drawn to the city’s little-known medieval remains, but the digs have also brought more recent parts of Berlin’s cityscape to light, including the city’s first power plant. In the fall of 2019, its warren of basements, mechanical access tunnels, and heavy machinery were still in place just a few feet away from city hall’s back doors. “To see a big electrical plant, with all the smoke and dust that comes with it, built right in the center of the city, shows the power of modernity,” Wemhoff says. Further discoveries include bomb craters and other signs of WWII damage, as well as mundane finds from the 1920s and 1930s: rusted typewriters, broken dishes from the municipal cafeteria, and other detritus of Berlin’s Weimar-era heyday.

The work has also courted controversy—nothing more so than a 180-foot-long stretch of an almost perfectly preserved oak log road that was uncovered in early 2022 almost eight feet below the modern street level just outside the city water authority’s headquarters. Analysis of tree rings shows that construction on the road began in 1215, more than 20 years before the city first appears in historical records, making it the city’s oldest road.

Almost immediately, Malliaris and Wemhoff were in a bind. Historians and preservation groups thought the dozens of 800-year-old logs should be preserved. Like the river dam, they are evidence that Berlin was well-organized and planned from the start, with a mayor or town council supervising complex infrastructure projects rather than a disorganized collection of merchants and fishermen.

Construction crews, however, needed to dig a trench through the logs to make room for electrical cables and were anxious about staying on schedule. Because the logs’ preservation depended on the wet, oxygen-free conditions underground, exposure to air immediately began to cause decay. Archaeologists, city planners, and the construction company reached a compromise: They would preserve an 18-by-18-foot piece of the road, starting the yearslong conservation process while they looked for a museum to house it. By late spring, the road was gone. A number of oak logs sat in a pool lined with black tarps, soaking until they could be moved to a conservation facility. Eventually they will go on display in a museum or in a building in the planned neighborhood, where a series of “archaeological windows” are planned to preserve slices of the city’s past for residents and tourists. Most of the road, however, has been destroyed. “We wanted to keep something in the ground, but there was a power line that had to go through,” Malliaris says. “It’s a typical urban archaeology problem.”

Malliaris and his team are documenting everything they find and trying to save some of it. The decisions can be difficult. What should they do, for example, with the remains of the electrical plant or 1930s-era cups and plates? “From an archaeological point of view, the hardest thing is these mass finds from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,” Malliaris says. “The medieval period fascinates people, but so does the electrical plant. What do we keep, and what do we throw away?” Documenting the more modern finds has also been a challenge. “Industrial artifacts are very specialized; for example, part of a motor or an early electrical isolator—we aren’t trained to identify that stuff,” Malliaris says. “In the Middle Ages, it’s more likely to be a plate or a pot made by hand. It’s a lot easier.”

Artifacts of the recent past can pose other unique challenges. In January 2020, just months into the excavations, workers clearing topsoil uncovered a WWII-era bomb. The unexploded 500-pound ordnance was German-made and had likely been captured and repurposed by Soviet forces in their final push to conquer the city. After the archaeologists were evacuated, police asked residents in the surrounding neighborhoods to clear out as well. A special police unit removed the bomb and detonated it.

As Malliaris and his team finish excavating a section of the site, bulldozers and backhoes move in, covering the ruins with soil once more. A few years from now, new apartment buildings will go up, either destroying what’s left underground or sealing it off. “We’re standing on a thirteenth-century street, but when they start building here, it’ll be 2.5 meters deep again,” Malliaris says. For now, though, there’s no time to sit back and appreciate the finds. Just a few yards away, backhoe drivers are busy shifting dirt and cutting trenches for power lines and sewer pipes, the infrastructure the new neighborhood will need.