Pearl Harbor

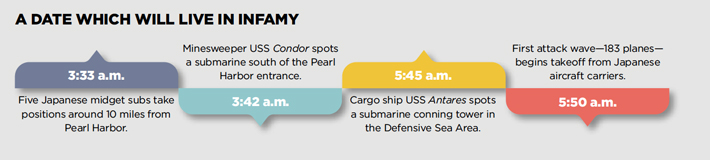

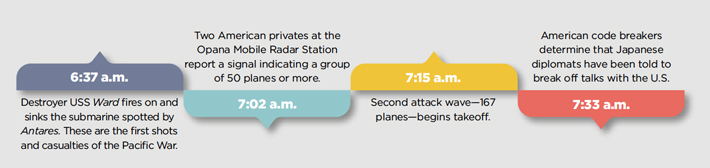

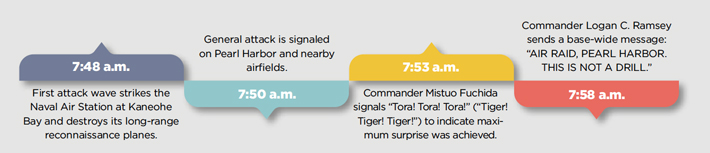

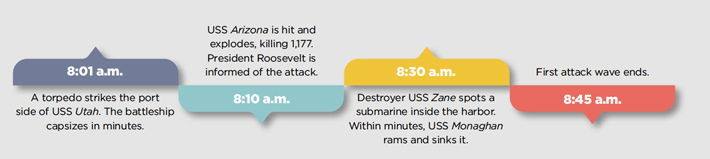

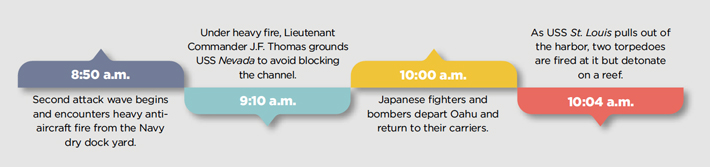

A Timeline of the Attack

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, December 01, 2016

DECEMBER 7, 1941

The Seaplane

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, December 01, 2016

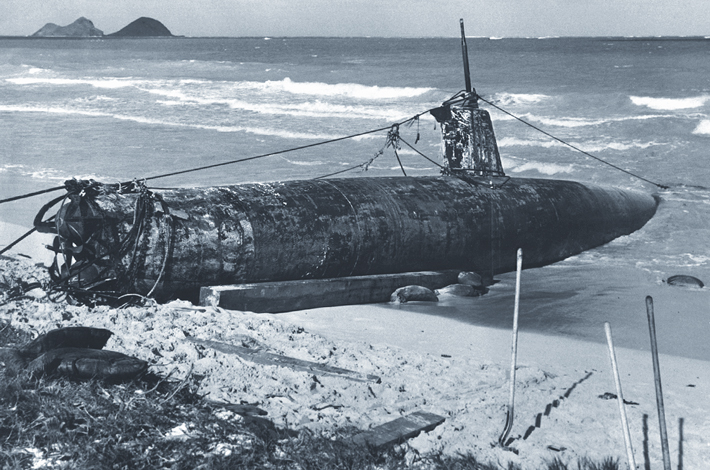

In the attack, 75 percent of the U.S. planes sitting at airfields near Pearl Harbor were damaged or destroyed. For all the aircraft lost—the Japanese lost 59—there is one that can be linked to that morning. Very few people can gain access to it, and even then only with a military escort, since it lies in the water just off Marine Corps Base Hawaii at Kaneohe Bay, on the east side of Oahu. During the war, this was the location of a Naval Air Station for PBY-5 Catalina seaplanes, long-range reconnaissance craft.

The Japanese knew that these planes could track them to their carriers north of the island. The PBY-5s had a range of almost 1,500 miles and could be in the air in minutes. So, just before the general attack, at 7:48 a.m., attacking planes strafed the Naval Air Station with 20 mm incendiary rounds and bombs. Of the 36 planes there, three were out on patrol, six were damaged, and the rest were destroyed. Servicemen at Kaneohe Bay scrambled to put out fires and salvage what they could.

In the 1980s, the mooring area was used for training mine-detecting dolphins. That could be when the battered wreck of one of the PBY-5s was first identified. In 1994, students and archaeologists from the University of Hawaii and East Carolina University surveyed the remains. “It was a good start on the submerged story,” says Hans Van Tilburg, who was on that team and is now a maritime heritage coordinator with NOAA. In 2000, the University of Hawaii returned to the site for surveys that turned up aviation-related scraps, but no other planes. It’s possible that the others had been salvaged or drifted into deeper, murkier water. “Our desire is to get back to the bay and continue looking in deeper water,” says Van Tilburg.

In the 1980s, the mooring area was used for training mine-detecting dolphins. That could be when the battered wreck of one of the PBY-5s was first identified. In 1994, students and archaeologists from the University of Hawaii and East Carolina University surveyed the remains. “It was a good start on the submerged story,” says Hans Van Tilburg, who was on that team and is now a maritime heritage coordinator with NOAA. In 2000, the University of Hawaii returned to the site for surveys that turned up aviation-related scraps, but no other planes. It’s possible that the others had been salvaged or drifted into deeper, murkier water. “Our desire is to get back to the bay and continue looking in deeper water,” says Van Tilburg.

The remains of the plane consist of the forward portion of its fuselage, including the cockpit and turret, which lies on its starboard side in about 30 feet of water, the starboard half of the 105-foot parasol wing, and the fragmented remains of the tail 30 feet away. It is likely that fuel tanks in the center of the wing exploded, but the wrecked seaplane holds telling details about the frantic eight minutes of that initial Japanese attack.

There is a large gash in the port side, just where a propeller would have been. Inside the cockpit, the port throttle is in the forward position. Yet the plane is still attached to its mooring line. This all suggests that an attempt was made to scramble at least one of the planes—but that it didn’t get far. The wreck does not provide evidence of what happened to the pilot, or just how many planes were moored at Kaneohe that morning. Some sources say three, others four, and there are six in a drawing by a Japanese pilot. “Every eyewitness account contradicts the other accounts,” says Van Tilburg. “It’s still a bit of a mystery. But this might be the only plane we know of that we can point to and say, ‘This is a December 7 casualty.’”

The Battleships

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, December 01, 2016

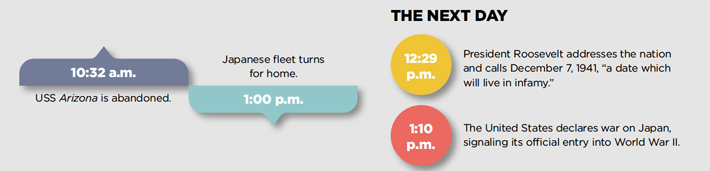

The broken remains of the battleship USS Arizona, in shallow water off Ford Island, are a war grave, a pilgrimage site, a potential environmental nightmare, and a focal point for the study of shipwrecks around the world and the archaeological landscape of World War II. Arizona, commissioned on October 16, 1916, was the second and last battleship in the Pennsylvania “super-dreadnought” class: 608 feet long, 33,000 horsepower, armed with 12 14-inch guns and around 30 smaller ones, and with armor up to 18 inches thick. It saw little action before it entered Pearl Harbor for the last time on December 6, 1941, and docked in berth F-7, where the repair ship USS Vestal pulled alongside it.

Arizona began to take fire almost as soon as the attack began, and men scrambled across the teak deck fighting fires. There are reports that its bottom was blown out by a torpedo that slid in under Vestal, around the same time that a torpedo fatally struck USS Utah, an older battleship used for anti-aircraft training. Then, at 8:10 a.m., crack Japanese bombardier Noburo Kanai loosed a 1,760-pound armor-piercing bomb that penetrated Arizona’s deck beside the No. 2 turret and detonated the forward magazine, killing 1,177 men. At 10:32 a.m., 30 minutes after the attack ended, the ship was declared untenable and abandoned. It burned for days.

Within a week, Navy divers were examining Arizona, and over the next two years they removed turrets, sensitive material, live ammunition, machinery, the masts—and 105 bodies, though those efforts were stopped due to manpower limitations, safety concerns, and the emotional toll on the divers. In December 1942 Arizona was struck from the books of commissioned ships, its remaining casualties declared buried at sea. It was one of the three ships damaged in the attack that did not return to service, along with Utah, which still sits in the harbor, and USS Oklahoma, which was refloated but sold for scrap and lost in a storm in 1947. Dave Conlin, chief of the National Park Service (NPS) Submerged Resources Center (SRC), has led recent studies of the wreck and says, “Had Arizona not been so catastrophically wounded by the attack, or Utah been righted like they were trying to do, there would be almost no indications of what happened here.”

Once the salvage ended, no one systematically examined the wreck until NPS took over management of the site in 1980. Its condition at the time, according to a later NPS report, was “riddled with contradiction and mystery.” The SRC (then called the Submerged Cultural Resources Unit) and the Navy Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit One planned a series of dive seasons. The project began in 1983 with an unexpected revelation. It had been thought that all four of Arizona’s turrets had been removed or destroyed. But just aft of the explosion damage, divers found the No. 1 turret—intact. “Three battleship guns in a turret as big as a Greyhound bus, at a depth of 29 feet. How is it that they didn’t know about that?” says Conlin. “Everyone thought all the turrets had been removed. Unbelievable.”

The next year, NPS and the Navy began a foot-by-foot inspection and mapping project to assess the wreck and look for evidence of undocumented operational modifications, battle damage, and salvage efforts. This had never been attempted on a wreck of this scale. There were no guidelines to follow, no relevant experience or technology, save string, clothespins, measuring tape, plastic protractors, and some electronic measuring tools. But they had some expertise, particularly that of NPS’s Larry Nordby, whose work measuring cliff dwellings in the Southwest helped them adjust for the curvature of the ship. Those original measurements, according to Scott Pawlowski, chief of cultural and natural resources at the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument, “were just damn good.” They found that the hull plates had ripped outward 20 feet at the point of the explosion like an over-pressurized tin can. They retrieved potentially explosive materials, observed items from dishes to a Coke bottle to a fire hose, and could not find evidence of a torpedo strike. Of diving on the wreck during this time, when he was with NPS, NOAA’s James Delgado says, “It connects you to the human events that happened, those details that are intimate and personal, beyond the iconic image of a burning battleship.”

The project continued in the following years with the mapping of Utah, an often-forgotten casualty of the attack, and an unsuccessful scan for crashed aircraft and submarines. Of major concern were Arizona’s structural integrity and the estimated 500,000 gallons of bunker C fuel oil inside. Around a gallon a day still leaks from the wreck, a bright sheen visible to every visitor to the memorial. Another phase of research began around 2000 and applied the latest technology and modeling to understand how the ship is changing. Arizona has since become the best-characterized metal wreck in the world. Working with the Navy, National Institute of Standards and Technology, University of Nebraska, U.S. Geological Survey, and other partners, NPS created a detailed model of the stresses on the ship. They have studied the microbes, chemical decay products, water flow, the sediment and rock beneath it. They’re using sonar, 3-D imaging, hyperspectral cameras. “We’re bringing all these data sets together,” says Pawlowski.

The project continued in the following years with the mapping of Utah, an often-forgotten casualty of the attack, and an unsuccessful scan for crashed aircraft and submarines. Of major concern were Arizona’s structural integrity and the estimated 500,000 gallons of bunker C fuel oil inside. Around a gallon a day still leaks from the wreck, a bright sheen visible to every visitor to the memorial. Another phase of research began around 2000 and applied the latest technology and modeling to understand how the ship is changing. Arizona has since become the best-characterized metal wreck in the world. Working with the Navy, National Institute of Standards and Technology, University of Nebraska, U.S. Geological Survey, and other partners, NPS created a detailed model of the stresses on the ship. They have studied the microbes, chemical decay products, water flow, the sediment and rock beneath it. They’re using sonar, 3-D imaging, hyperspectral cameras. “We’re bringing all these data sets together,” says Pawlowski.

“What we learned is that, yes, Arizona is corroding. Yes, Arizona is rusting. And yes, Arizona is changing,” says Conlin, “but it’s changing very, very slowly, and the best science that we have tells us that Arizona will still have significant structural integrity for at least another 150 years.” The risk of a catastrophic spill is low, he adds. Battleships don’t hold oil in a single tank, but in hundreds of cells. A recent SRC study found that, of the several places where oil emerges from the wreck, only one appears to be closely connected to a fuel storage area. The rest of the leaking oil follows a circuitous path through interior spaces, which suggests that it is distributed around the ship. Furthermore, it is thought that the oil inside inhibits the degradation of the metal and provides a buoyant force for its structure. And there’s no way to remove the oil without deeply impacting or damaging a war grave. “We are getting smarter about how we can understand Arizona,” Conlin says, “and also how we can manage Arizona.”

Another recent project has involved entering the wreck with an innovative new remotely operated vehicle developed by the Advanced Imaging and Visualization Lab at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, which will be used to create 3-D models of some interior spaces of the ship, measure sediment accumulation, and collect microbial communities from inside. Such sensitive work, Conlin explains, is not undertaken lightly and is not just to feed curiosity, but is in service of preservation and stewardship of the wreck and others like it. “What started as an iconic battleship, the way it was in the 1980s, becomes something more,” says Delgado. “The development of the field of marine, maritime, and nautical archaeology—you can really see it in a microcosm with the way work on Arizona has advanced.”

The Submarines

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, December 01, 2016

The first shot of the Pacific War was not fired from a Japanese fighter, but from an American destroyer, more than an hour before the attack began. At 5:45 a.m., the cargo ship USS Antares spotted an object that might have been a submarine in the Defensive Sea Area outside Pearl Harbor. The destroyer USS Ward fired on it twice around 6:37 a.m. The second shot found its mark, and the object sank beneath Ward. On board this secret Japanese submarine, two young operators became the first casualties of the Pacific War.

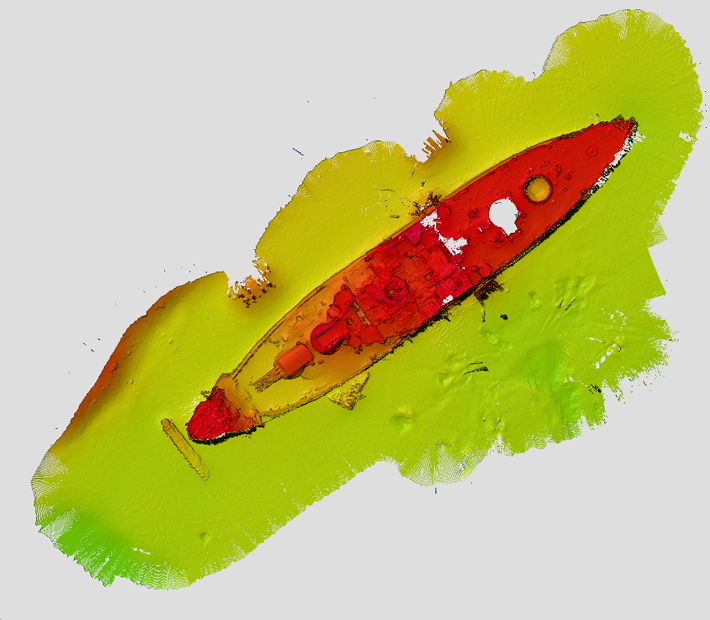

Sub sightings continued throughout the attack, on both sides of the harbor entrance and even within it, where at around 8:30 a.m. the destroyer USS Monaghan rammed and sank another. Early the next morning, a small sub and a surviving crewman, Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki, washed ashore on the east side of Oahu. Sakamaki became America’s first prisoner of war, and the Navy got a close look at what they had been firing at.

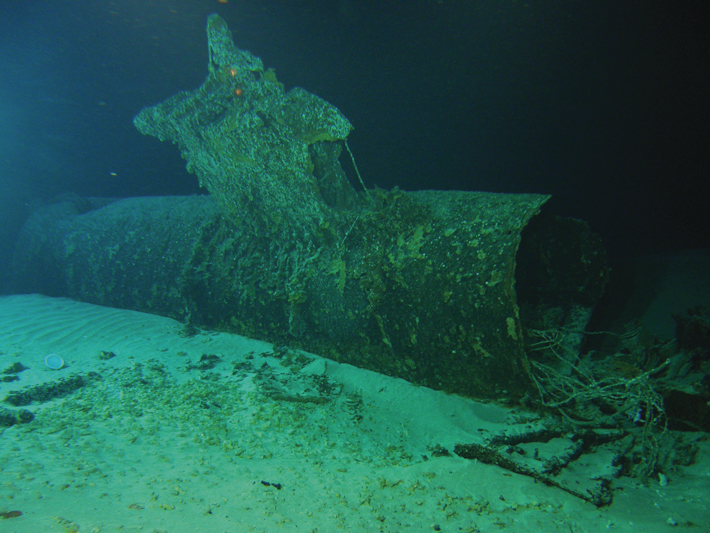

The subs are known as Type A Kō-hyōteki–class subs, and it is now known that five were deployed in the attack. Just 81 feet long and 6 feet in diameter, with a crew of two and a 600-horsepower electric motor, each “midget” sub was transported, piggyback, on a larger submarine. They fanned out around 10 miles from the harbor entrance early on the morning of December 7. Their plan was to enter the harbor one by one, wait out the attack, and then fire their torpedoes that night. Though their role in the attack was lauded in Japan, they weren’t successful in this particular mission.

The fates of some of these subs have been a mystery. Sakamaki’s is now on display at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas. The one rammed by Monaghan was raised and buried at Pearl Harbor in 1942. In June 1960, another was found by a Navy diver at Keehi Lagoon, east of the harbor entrance. The bow was removed and dumped, and the rest sent back to Japan, where it was restored and put on display at the Naval Academy at Etajima (now the Naval History Museum). That left two: the one sunk by Ward and another that may or may not have made it into the harbor.

Concerted searches for the subs began in the 1980s. Most were conducted by the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL), which operates two submersibles that ferry scientists and filmmakers to the deep ocean. Before each season, the subs do a series of dives to test their equipment. Since the early 1990s, HURL’s chief submersible pilot Terry Kerby has used the dives to search for wrecks, the midget subs in particular. “If we could use those test dives in an area where we might find something,” he says, “then we would do it.” They have made dozens of finds this way, from an old Studebaker to a Japanese aircraft-carrying submarine.

In 1992, HURL found the stern section of a midget sub, followed by the midsection in 2000 and the bow in 2001. This sub was not identified at the time, but became known as the “three-piece.” In 2002, while investigating a sonar target just outside the Defensive Sea Area, HURL found another sub, intact. They saw, just where the conning tower meets the hull, the hole made by the first shot of the war. Survey showed that Ward’s shot struck a support frame and deflected downward, creating a vent hole in the bottom of the sub, which explains why it didn’t implode as it porpoised to a soft landing a mile from its fatal encounter. “It took 10 years, but we finally found it,” says Kerby. “It was in perfect condition.”

That left the three-piece. One theory about this sub is that it made it into the harbor, all the way to the backwater called West Loch, where it fired its torpedoes and set off its scuttling charge. Then, following the West Loch disaster, a massive accidental explosion in 1944, it was picked up, cut into pieces, and disposed of. A new analysis by NOAA and HURL, which returned to examine the sub in 2013, proposes an alternate explanation. The cruiser USS St. Louis reported that as it exited the harbor at the end of the attack, two torpedoes were fired at it but struck a reef. NOAA’s James Delgado and his team found a new piece of evidence to support this—a report that a 1950–1951 marine science expedition led by George Vanderbilt III stumbled across a midget sub, blown in half, near where St. Louis had been fired upon. The report, sent to LIFE magazine by an intelligence officer named Captain Roger Pineau, stated that the sub was hauled up, cut further, and dumped. The remains of a Japanese serviceman were found nearby a few days later. Delgado and his coauthors conclude that the three-piece is indeed the final sub from the attack, but that it probably never made the difficult journey into the harbor. It was likely waiting next to the harbor entrance—like the one discovered on the other side in 1960—to block it by sinking ships as they fled the attack.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement