Taxes

Royal Food Fund

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

During the second millennium B.C., the Hittite kings relied on their control of staple crops to maintain their expanding empire in central Anatolia, where rainfall was unpredictable. At state-sponsored religious festivals, the king presided over feasts where he redistributed surplus crops such as grain. A portion of this grain was stored in long-term reserves for use as seed to sow fields the next year and to supplement food supplies in lean years. While Hittite religious texts describe these festival rations, and surviving law codes detail other taxes on produce owed to the state, no records of how taxes were actually paid have been discovered, as they have in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeological remains of grain silos offer the only glimpse into how the Hittite tax system functioned.

During the second millennium B.C., the Hittite kings relied on their control of staple crops to maintain their expanding empire in central Anatolia, where rainfall was unpredictable. At state-sponsored religious festivals, the king presided over feasts where he redistributed surplus crops such as grain. A portion of this grain was stored in long-term reserves for use as seed to sow fields the next year and to supplement food supplies in lean years. While Hittite religious texts describe these festival rations, and surviving law codes detail other taxes on produce owed to the state, no records of how taxes were actually paid have been discovered, as they have in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeological remains of grain silos offer the only glimpse into how the Hittite tax system functioned.

At their capital city of Hattusha around 1600 B.C., the Hittites constructed one such underground storage complex that was partially destroyed by fire shortly thereafter. Excavated by the German Archaeological Institute, the silo’s 32 hermetically sealed chambers were found to contain several hundred tons of cereal grain, primarily hulled barley and wheat. Researchers estimate that when filled to capacity, the silo’s stores could have fed between 20,000 and 30,000 people for one year. By analyzing isotopes in grain samples from the silo, a team led by archaeobotanist Charlotte Diffey of the University of Reading has recently determined that crops stored in five separate chambers were grown with varying levels of water, manure, and human labor. “The grain wasn’t coming from one location,” says Diffey, “but rather from a variety of rural settlements within the Hattusha hinterland.” She and her colleagues think the grain stored at Hattusha represents taxes collected from different farming communities with differing degrees of wealth and access to agricultural resources. A surprisingly high proportion of weed seeds identified in the silo samples suggests that state oversight of taxed crops was rather lax. Whether taxes were assessed by crop weight or the size of land holdings, Diffey explains, Hittite farmers likely used the system to their advantage, leaving weeds in with the harvested grain, perhaps to skimp on the taxes they owed.

At their capital city of Hattusha around 1600 B.C., the Hittites constructed one such underground storage complex that was partially destroyed by fire shortly thereafter. Excavated by the German Archaeological Institute, the silo’s 32 hermetically sealed chambers were found to contain several hundred tons of cereal grain, primarily hulled barley and wheat. Researchers estimate that when filled to capacity, the silo’s stores could have fed between 20,000 and 30,000 people for one year. By analyzing isotopes in grain samples from the silo, a team led by archaeobotanist Charlotte Diffey of the University of Reading has recently determined that crops stored in five separate chambers were grown with varying levels of water, manure, and human labor. “The grain wasn’t coming from one location,” says Diffey, “but rather from a variety of rural settlements within the Hattusha hinterland.” She and her colleagues think the grain stored at Hattusha represents taxes collected from different farming communities with differing degrees of wealth and access to agricultural resources. A surprisingly high proportion of weed seeds identified in the silo samples suggests that state oversight of taxed crops was rather lax. Whether taxes were assessed by crop weight or the size of land holdings, Diffey explains, Hittite farmers likely used the system to their advantage, leaving weeds in with the harvested grain, perhaps to skimp on the taxes they owed.

Render Unto Pharaoh

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

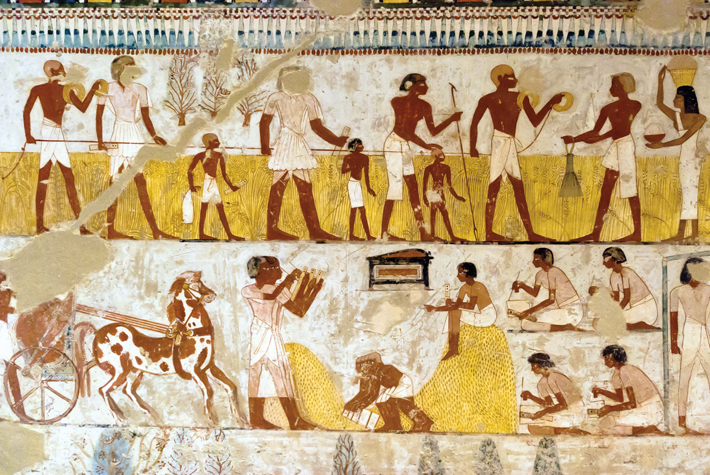

Throughout ancient Egyptian history, taxes were very much part of daily life. Most Egyptians were farmers who owed the state both a period of labor service and a portion of their annual harvest. The pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.) levied these taxes on villages and towns collectively. When communities failed to fulfill their tax quotas, their administrators were held accountable. “The penalties could be quite severe,” says University of Chicago Egyptologist Brian Muhs. “We have depictions in mortuary chapels of town chiefs being beaten in front of scribes for failing to pay taxes.”

Throughout ancient Egyptian history, taxes were very much part of daily life. Most Egyptians were farmers who owed the state both a period of labor service and a portion of their annual harvest. The pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.) levied these taxes on villages and towns collectively. When communities failed to fulfill their tax quotas, their administrators were held accountable. “The penalties could be quite severe,” says University of Chicago Egyptologist Brian Muhs. “We have depictions in mortuary chapels of town chiefs being beaten in front of scribes for failing to pay taxes.”

Muhs points out that it was probably a great relief to these local administrators that during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), the Egyptian state began to tax individual people and fields, rather than communities. This was only possible due to the exponential growth in the number and abilities of Middle Kingdom scribes, who developed land registers and censuses to keep track of individuals’ tax obligations. “It was a new technological as well as social environment,” says Muhs. “There were thousands of scribes who could use documentation as a powerful tool to make sure everyone paid their taxes.”

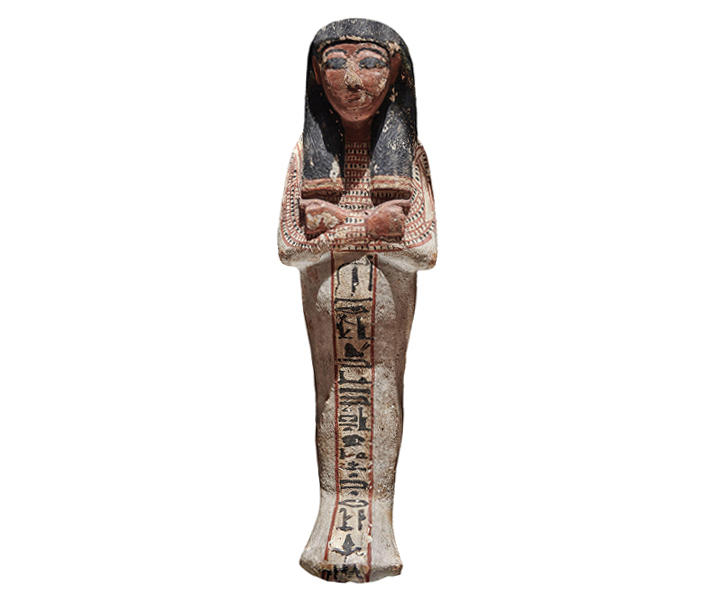

Ancient Egyptians assumed that they would have to pay taxes in the afterlife, too—and that the system could be gamed. “In life, privileged Egyptians could send a substitute to perform their labor taxes for them,” says Muhs, “so they came to believe that something similar could be done in the afterlife.” During the Middle Kingdom, Egyptians began including small figurines, known as ushabti, in their graves. Ushabti were inscribed with spells ensuring the figurines would perform their deceased owner’s labor taxes when called upon. For the next 2,000 years, ushabti helped Egyptians—high status and commoner alike—dodge their taxes for eternity.

Spoils of War

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

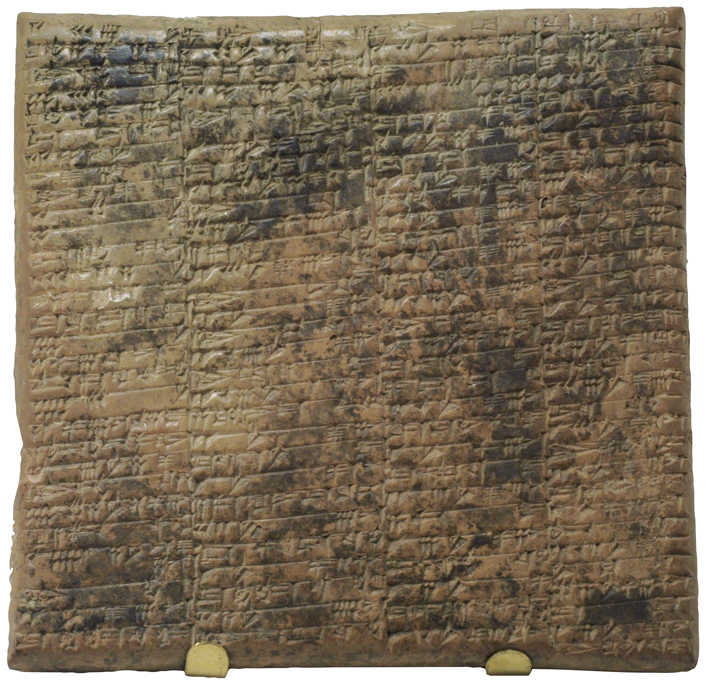

Around 2112 B.C., the Sumerian king Ur-Namma (r. 2112–2095 B.C.) united the city-states of southern Mesopotamia into a short-lived kingdom known today as the Third Dynasty of Ur, or Ur III. More than 100,000 clay cuneiform tablets, many recording taxes paid to the royal household, date to this era. “It’s one of the most documented periods in the ancient world,” says Western Washington University Assyriologist Steven Garfinkle. “In some cases we can track a single sheep through the tax system across multiple tablets, all the way to the king’s kitchens.” The taxes the Ur III kings levied relied on the bala system, a local tax that was probably already more than 1,000 years old by that point. The rulers also collected direct payments from a new class of nobles empowered by the rise of the Ur III state—who may have even welcomed paying taxes. “These new local elites relied on the royal recognition of their property rights,” says Garfinkle, “and paying taxes to the king was one way to ensure the legitimacy of their new status.”

Around 2112 B.C., the Sumerian king Ur-Namma (r. 2112–2095 B.C.) united the city-states of southern Mesopotamia into a short-lived kingdom known today as the Third Dynasty of Ur, or Ur III. More than 100,000 clay cuneiform tablets, many recording taxes paid to the royal household, date to this era. “It’s one of the most documented periods in the ancient world,” says Western Washington University Assyriologist Steven Garfinkle. “In some cases we can track a single sheep through the tax system across multiple tablets, all the way to the king’s kitchens.” The taxes the Ur III kings levied relied on the bala system, a local tax that was probably already more than 1,000 years old by that point. The rulers also collected direct payments from a new class of nobles empowered by the rise of the Ur III state—who may have even welcomed paying taxes. “These new local elites relied on the royal recognition of their property rights,” says Garfinkle, “and paying taxes to the king was one way to ensure the legitimacy of their new status.”

These newly powerful figures were able to pay their taxes by joining the king on annual raids against people living on the periphery of the Ur III state, especially to the east in present-day Iran. There they captured great quantities of sheep, slaves, and other plunder, part of which they then turned over to the king, who relied heavily on these payments. “We’re tempted to think of Ur III as this powerful centralized state,” says Garfinkle. “But close study of the tablets and the tax system shows that it was actually quite fragile and dependent on nearly constant warfare.”

A century after the kingdom’s founding, the power of the kings of Ur waned and they were no longer able to lead the raiding campaigns that had been so critical to their survival. Around 2004 B.C., the rulers of Elam, a land to the east of Mesopotamia that was one of the most frequent targets of the Ur III raids, turned the tables and deposed the last Ur III king, Ibbi-Sin, who was taken away to Elam in chains.

Advertisement

Page 2 of 2

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement