Online Exclusives

A Community's Roots

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, February 02, 2017

Originally published in the November/December 2006 issue

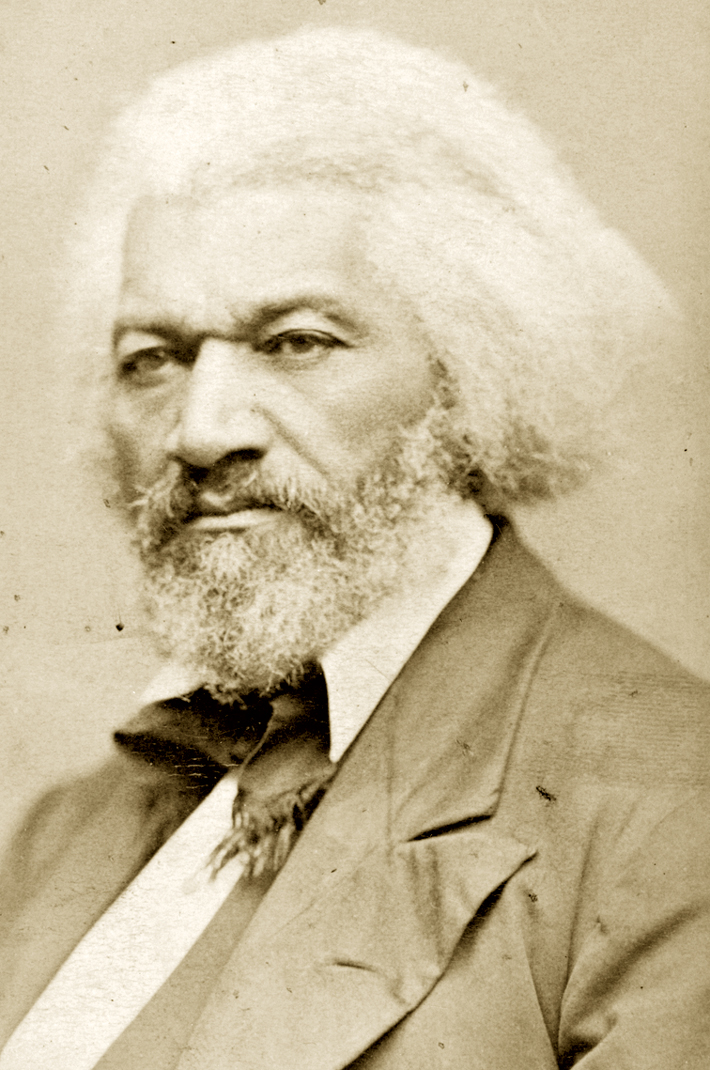

In Talbot County, Eastern Shore, State of Maryland, near Easton, the county town, there is a small district of country, thinly populated, and remarkable for nothing that I know of more than for the worn-out, sandy, desert-like appearance of its soil, the general dilapidation of its farms and fences, the indigent and spiritless character of its inhabitants, and the prevalence of ague and fever. It was in this dull, flat, and unthrifty district or neighborhood, bordered by the Choptank river, among the laziest and muddiest of streams surrounded by a white population of the lowest order, indolent and drunken to a proverb, and among slaves who, in point of ignorance and indolence, were fully in accord with their surroundings, that I, without any fault of my own, was born, and spent the first years of my childhood. —FREDERICK DOUGLASS, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881)

******************************************

Under the boughs of a huge tulip poplar, buried among clumps of roots and piles of oyster shells, is the brick foundation of a building, a remnant of a once-thriving slave community. For 18 months in the early nineteenth century, it was home to a young Frederick Douglass, the future African-American statesman, diplomat, orator, and author. Here, at the age of seven or eight, a shoeless, pantless, precocious Douglass first saw whippings and petty cruelties. Here, he first realized he was a slave. “A lot of the horror that comes through his autobiographies is grounded in those months that he was there,” says James Oakes, a historian at the City University of New York who is working on a book about Douglass’s relationship with Abraham Lincoln. The modest excavation at Wye House Farm, a 350-year-old estate on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, has yielded sherds, buttons, pipe stems, beads, and precious knowledge about everyday slave life, and is allowing the descendants of that slave community, many of whom live in the nearby rural African-American town of Unionville, to reclaim a lost cultural hertiage.

A team of archaeologists and students started digging here in 2005 after archaeologist Lisa Kraus proposed the dig, on the basis of Douglass’s descriptions of the site, to Mark Leone, director of the urban archaeology field school at the University of Maryland. Before beginning the excavation, Leone approached St. Stephen’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, the social and religious center of Unionville, to ask what the people of the community wanted to learn from the archaeology. “You should ask the people who think it’s their heritage what they want to know about it,” Leone says. “The answers automatically dissolve the difference between then and now.” This, he adds, is the heart of social archaeology, working with descendant communities and understanding that the past and present inform one another. The people of Unionville wanted to know about slave spirituality, what remained of African life, how the owner of the slaves did or did not support freedom, and how slaves found the strength to survive. They are questions a single dig is unlikely to answer, but they have opened an avenue of dialogue between the archaeologists and the people to whom their work matters most.

A sharp, fetid smell wafts off the nearby cove, where swarms of insects form a halo over still water. Leone, a tall, fair anthropologist who has spent his career studying class and race in the historical landscape of Annapolis, speaks slowly and deliberately. “What we have discovered is there’s archaeology everywhere,” he says, as a team of students profile and photograph the site under the tulip poplar behind him. “We’ve only scratched the surface.” Waving his hand across the rolling landscape bordered by the cove on one side and a farm road on the other, he explains that it was once all part of a slave community buzzing with activity.

Leone and Kraus, a graduate student at the University of Texas, have for the last two field seasons led this dig, which is on the grounds of a grand plantation that has been, and still is, privately owned by one family—the Lloyds, one of the founding families of Maryland. The team so far has uncovered three structures packed with domestic and commercial artifacts of slave life, and they expect to find more next season.

Mary Tilghman, the Lloyd family matriarch and eleventh-generation descendant of Edward Lloyd, who settled the property in the 1660s, receives guests in the well-appointed, hunting-themed south parlor of the estate’s late Georgian mansion, just a hundred yards or so from the dig site. Tilghman, a proper yet lively woman of 87, dressed in a long khaki skirt and collared blouse, has piercing blue eyes and pale skin like creased parchment. She taps her aluminum cane on the hardwood floor as she speaks. “I think it’s fascinating and I think seeing something, rather than assuming something was there, that’s intriguing, This is probably a very foreign culture to a great many people.”

Plain of Jars

By KAREN COATES

Monday, December 12, 2016

Editor's Note: Originally published in the July/August 2005 issue

I’m following Belgian archaeologist Julie Van Den Bergh around Laos’ remote Xieng Khouang Province. We’re inspecting giant ancient vessels, which are scattered through rice paddies, forests, and hilltops at more than 60 sites across what is known as the Plain of Jars. Archaeologists think the jars were mortuary containers, perhaps 2,000 years old. But no one knows for sure their precise age, who built them, or why. They are swathed in mystery and surrounded by unexploded bombs.

Xieng Khouang Province is one of the most heavily bombed places on earth. Between 1964 and 1973, the United States dumped four billion pounds of bombs on the country in a “secret war” against Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese communists. Up to a third of them never exploded, and they litter the land today. While generally safe to tread upon, buried UXO (unexploded ordnance) can detonate when an erratic fuse is inadvertently triggered. The earth around here is dangerous to farmers plowing fields, children staking buffalo out to graze—and to archaeologists.

The jars are huge, up to nine feet tall, the largest weighing 14 tons. Most are carved of sandstone, others of granite, conglomerate, or calcified coral. Some are round, others angular, and a few have disks that appear to be lids. Tools and human remains found inside and around the jars suggest their use and manufacture spanned centuries. The bulk of material dates from 500 B.C. to A.D. 800, and additional carbon dates are expected this summer.

Archaeologists are certain the Plain of Jars is one of Southeast Asia’s most important archaeological sites—but it is one with more questions than answers.

French archaeologist Madeleine Colani pioneered research in Xieng Khouang in the 1930s. She found jars with cremated human remains and a nearby cave with burned bones and ash. Colani speculated the cave was a crematorium, the jars were mortuary vessels, and the fields were ancient cemeteries. Today, more than 2,000 jars have been identified across the province.

These archaeological treasures sit in one of the world’s poorest regions. That’s why Van Den Bergh, a UNESCO consultant from the Hong Kong–based Archaeological Assessments, is here. She hopes to turn the Plain of Jars into a UNESCO World Heritage site. The UNESCO-Lao Project to Safeguard the Plain of Jars aims not only to protect the vessels but to rehabilitate this remote province by clearing bombs, restoring agricultural lands, and promoting tourism.

A specialist in geoarchaeology with a decade of experience in Asia, Van Den Bergh has worked in Laos on six-week stints for four years now. In conjunction with the Lao government and a geographer from Bangkok, the project includes training Laotians to recover, record, and store archaeological material; create a precise map of the jar fields; and identify key areas for preservation and tourism development. The project also enlists local villagers to help with these tasks and involves the British-based Mines Advisory Group (MAG), a non-governmental organization hired to remove explosives from the most popular jar sites.

Some dub the Plain of Jars “the world’s most dangerous archaeological site,” and Van Den Bergh readily agrees. While archaeologists occasionally encounter UXO in war-torn countries and military testing grounds around the world, perhaps no archaeological site is as contaminated as the Plain of Jars. Two archaeologists conducted limited excavations in the 1990s without incident, “but that’s just luck,” Van Den Bergh says. “I’ve come home from surveying and thought, I’m happy to be getting into the car and coming home.”

Return to the Trail of Tears

By MARION BLACKBURN

Tuesday, April 05, 2016

Long time we travel on way to new land. People feel bad when they leave Old Nation. Women cry and made sad wails. Children cry and many men cry, and all look sad like when friends die, but they say nothing and just put heads down and keep on go towards West. Many days pass and people die very much.

—A Cherokee account from The Oklahoman, 1929, cited by John Ehle in Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation, 1988

It’s easy to miss this subtle groove, covered in pine straw and vines, worn in the ground of eastern Tennessee. In the summer of 1838, about 13,000 Cherokee walked this path from their homes in the Appalachian Mountains to a new, government-mandated homeland in Oklahoma. They traveled over land and water and were held in military camps along the way. Unlike other settlers heading west, who saw in America’s open expanses the hope of a new life, the Cherokee traveled with a military escort. They left behind highly coveted land that was, even as they walked, being divided up among white land speculators.

The Trail of Tears was a journey of some 900 miles that took approximately nine months to complete. After they were rounded up from their villages and homes, the Cherokee were assembled in large internment camps, where some waited for weeks before heading out in waves of approximately 1,000, following different paths, depending on the season.

As many as 4,000 died along the way from dehydration, tuberculosis, whooping cough, and other hardships— by some accounts, a dozen or more were buried at each stop. Some escaped along the way and were caught and returned to the march like criminals. Still others refused to leave, hiding out in the mountains, joining others on small farms where, stripped of tribal connections and burdened with unclear legal status, they faced an uncertain future.

Despite all our historical knowledge of the forced removal, there has been little study of the archaeology of the trail, the internment camps along the way, and the farms that sheltered those who stayed behind. The military forts that held the Cherokee in crowded, unsanitary conditions have been largely consumed by development or otherwise lost. The homesteads back East, where resistors lived under constant threat of arrest, went undocumented. Buildings, roads, farms, and floods have claimed almost all of these sites. In addition to a lack of material evidence, there has long been an uneasy, even contentious, relationship between Native Americans and archaeologists. Through neglect and distrust, this sad chapter has been at risk of fading from collective memory, taking with it any chance to understand the relationships between refugees and soldiers, and cultural information about the Cherokee themselves—what they carried, how they traveled, why they died.

That now stands to change. In eastern Tennessee, archaeologists are excavating the site of Fort Armistead, a U.S. Army encampment that served as a holding area and one of the first stops for North Carolina Cherokee on their forced journey west. Hidden deep in Cherokee National Forest, the site has managed to escape the damage or destruction that has visited nearly every other significant trace of the trail and camps.

December 7, 1941

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, December 01, 2016

The two hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, might be the most heavily documented and studied in history. There are eight official investigations, from a Naval Court of Inquiry to a Joint Congressional Committee, reams of records, and enough books, oral histories, documentaries, and feature films to fill a library. Yet there are still things that can be learned about the morning when 350 Japanese warplanes killed 2,403 Americans, wounded another 1,104, and sank or severely damaged 21 ships in a coordinated attack on military sites around Oahu, Hawaii.

A number of factors have obscured details—big and small—from that day. For example, the surprise of the attack complicated eyewitness accounts. Secrecy shrouded the active war effort on both sides. And, in the aftermath, the United States rushed to rebuild its naval power in the Pacific with the greatest maritime salvage project in history, which returned all but three of the damaged ships to service. This effort begins to explain why there are few archaeological sites directly tied to December 7.

In 2016, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management completed the first database of submerged cultural resources in the main Hawaiian Islands. Of 2,114 entries, just five come from the attack: two battleships in the harbor, two Japanese submarines in deep water, and a lone American seaplane. All were spared salvage—and in some cases discovery—for decades by some combination of depth, damage, and respect for the dead.

For the United States, Pearl Harbor stands alongside Yorktown, Gettysburg, Little Bighorn, and other iconic battlefields as a crucible of American identity. But it is different in both its freshness in memory and its inaccessibility, since most of the surviving remnants lie underwater, within active military installations, or both. It was 40 years before the underwater sites became the subject of archaeological inquiry. “We’re gaining a much more detailed understanding of the battlefield and all of its nuances,” says James Delgado, director of maritime heritage for NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, who has been directly involved in several of the archaeological projects at Pearl Harbor. “Seventy-five years on, the view is far more comprehensive and three-dimensional, not just in terms of the major events, but also individual experiences.”

For the United States, Pearl Harbor stands alongside Yorktown, Gettysburg, Little Bighorn, and other iconic battlefields as a crucible of American identity. But it is different in both its freshness in memory and its inaccessibility, since most of the surviving remnants lie underwater, within active military installations, or both. It was 40 years before the underwater sites became the subject of archaeological inquiry. “We’re gaining a much more detailed understanding of the battlefield and all of its nuances,” says James Delgado, director of maritime heritage for NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, who has been directly involved in several of the archaeological projects at Pearl Harbor. “Seventy-five years on, the view is far more comprehensive and three-dimensional, not just in terms of the major events, but also individual experiences.”

Today there are very few survivors of the attack, and fewer each year. The sites discussed here will soon be the only primary sources about an event that changed the course of the twentieth century. They are being studied not out of historical curiosity, but to ensure their stewardship for the future.

Trash Talk

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, January 13, 2015

In the middle of Rome’s trendiest neighborhood, surrounded by sushi restaurants and nightclubs with names like Rodeo Steakhouse and Love Story, sits the ancient world’s biggest garbage dump—a 150-foot-tall mountain of discarded Roman amphoras, the shipping drums of the ancient world. It takes about 20 minutes to walk around Monte Testaccio, from the Latin testa and Italian cocci, both meaning “potsherd.” But despite its size—almost a mile in circumference—it’s easy to walk by and not really notice unless you are headed for some excellent pizza at Velavevodetto, a restaurant literally stuck into the mountain’s side. Most local residents don’t know what’s underneath the grass, dust, and scattering of trees. Monte Testaccio looks like a big hill, and in Rome people are accustomed to hills.

Although a garbage dump may lack the attraction of the Forum or Colosseum, I have come to Rome to meet the team excavating Monte Testaccio and to learn how scholars are using its evidence to understand the ancient Roman economy. As the modern global economy depends on light sweet crude, so too the ancient Romans depended on oil—olive oil. And for more than 250 years, from at least the first century A.D., an enormous number of amphoras filled with olive oil came by ship from the Roman provinces into the city itself, where they were unloaded, emptied, and then taken to Monte Testaccio and thrown away. In the absence of written records or literature on the subject, studying these amphoras is the best way to answer some of the most vexing questions concerning the Roman economy—How did it operate? How much control did the emperor exert over it? Which sectors were supported by the state and which operated in a free market environment or in the private sector?

“ So, professor, just how many amphoras are there?” I ask José Remesal of the University of Barcelona, co-director of the Monte Testaccio excavations. It’s the same question that must occur to everyone who visits the site when they realize that the crunching sounds their footfalls make are not from walking on fallen leaves, but on pieces of amphoras. (Don’t worry, even the small pieces are very sturdy.) Remesal replies in his deep baritone, “Something like 25 million complete ones. Of course, it’s difficult to be exact,” he adds with a typical Mediterranean shrug. I, for one, find it hard to believe that the whole mountain is made of amphoras without any soil or rubble. Seeing the incredulous look on my face as I peer down into a 10-foot-deep trench, Remesal says, “Yes, it’s really only amphoras.” I can’t imagine another site in the world where archaeologists find so much—about a ton of pottery every day. On most Mediterranean excavations, pottery washing is an activity reserved for blisteringly hot afternoons when digging is impossible. Here, it is the only activity for most of Remesal’s team, an international group of specialists and students from Spain and the United States. During each year’s two-week field season, they wash and sort thousands of amphoras handles, bodies, shoulders, necks, and tops, counting and cataloguing, and always looking for stamped names, painted names, and numbers that tell each amphora’s story.

So, professor, just how many amphoras are there?” I ask José Remesal of the University of Barcelona, co-director of the Monte Testaccio excavations. It’s the same question that must occur to everyone who visits the site when they realize that the crunching sounds their footfalls make are not from walking on fallen leaves, but on pieces of amphoras. (Don’t worry, even the small pieces are very sturdy.) Remesal replies in his deep baritone, “Something like 25 million complete ones. Of course, it’s difficult to be exact,” he adds with a typical Mediterranean shrug. I, for one, find it hard to believe that the whole mountain is made of amphoras without any soil or rubble. Seeing the incredulous look on my face as I peer down into a 10-foot-deep trench, Remesal says, “Yes, it’s really only amphoras.” I can’t imagine another site in the world where archaeologists find so much—about a ton of pottery every day. On most Mediterranean excavations, pottery washing is an activity reserved for blisteringly hot afternoons when digging is impossible. Here, it is the only activity for most of Remesal’s team, an international group of specialists and students from Spain and the United States. During each year’s two-week field season, they wash and sort thousands of amphoras handles, bodies, shoulders, necks, and tops, counting and cataloguing, and always looking for stamped names, painted names, and numbers that tell each amphora’s story.

Although scholars worked at Monte Testaccio beginning in the late 19th century, it’s only within the past 30 years that they have embraced the role amphoras can play in understanding the nature of the Roman imperial economy. According to Remesal, the main challenge archaeologists and economic historians face is the lack of “serial documentation,” that is, documents for consecutive years that reflect a true chronology. This is what makes Monte Testaccio a unique record of Roman commerce and provides a vast amount of datable evidence in a clear and unambiguous sequence. “There’s no other place where you can study economic history, food production and distribution, and how the state controlled the transport of a product,” Remesal says. “It’s really remarkable.”

|

Slideshow:

|

What's in a Name?

|

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

During the Civil War, some local slaves enlisted in the Union Army, and their owners were compensated $300 each. Upon returning from the war, many of these newly freed men returned to the places that they knew. When 18 soldiers from this area—many of whom are thought to have come from Wye House Farm—returned, an abolitionist Quaker named Cowgill offered them a reasonable lease on land and the town of Unionville was founded. Just down the road from the farm, Unionville today is a poor but tidy rural town of single-family homes. The tightly knit and proud community is centered around St. Stephen’s and its adjoining graveyard, where the 18 soldiers are interred. Some of the names on the gravestones—Roberts, Demby, Bailey (Douglass’s birthname)—appear on the Lloyd’s slave rolls. Douglass even mentioned one, “Uncle” Isaac Copper, by name. Today, as in Douglass’s day, old money and rural poverty, divided along racial lines, sit side-by-side.

During the Civil War, some local slaves enlisted in the Union Army, and their owners were compensated $300 each. Upon returning from the war, many of these newly freed men returned to the places that they knew. When 18 soldiers from this area—many of whom are thought to have come from Wye House Farm—returned, an abolitionist Quaker named Cowgill offered them a reasonable lease on land and the town of Unionville was founded. Just down the road from the farm, Unionville today is a poor but tidy rural town of single-family homes. The tightly knit and proud community is centered around St. Stephen’s and its adjoining graveyard, where the 18 soldiers are interred. Some of the names on the gravestones—Roberts, Demby, Bailey (Douglass’s birthname)—appear on the Lloyd’s slave rolls. Douglass even mentioned one, “Uncle” Isaac Copper, by name. Today, as in Douglass’s day, old money and rural poverty, divided along racial lines, sit side-by-side.

“We have a history of African-American life that has this amazing time depth,” says Kraus. “Archaeology really gives us information about their day-to-day practices.” For example, pottery finds suggest that the slaves of Wye House Farm did not have access to a market or make ceramics themselves—most of what they used was passed down from the Lloyds. Other items, such as beads, buttons, and decorations, were probably not passed down and may have come, by night and by canoe, from a secret, prohibited trade network with other slave communities. Even though the slaves were worked almost constantly, and getting caught would have resulted in a beating from an overseer, they took great risks to build lives beyond the fields. “I don’t think that’s really been documented before,” says Kraus. With further analysis of the artifacts and where they were found, she hopes to discover how slave life may have changed over the decades that the site was occupied.

“We have a history of African-American life that has this amazing time depth,” says Kraus. “Archaeology really gives us information about their day-to-day practices.” For example, pottery finds suggest that the slaves of Wye House Farm did not have access to a market or make ceramics themselves—most of what they used was passed down from the Lloyds. Other items, such as beads, buttons, and decorations, were probably not passed down and may have come, by night and by canoe, from a secret, prohibited trade network with other slave communities. Even though the slaves were worked almost constantly, and getting caught would have resulted in a beating from an overseer, they took great risks to build lives beyond the fields. “I don’t think that’s really been documented before,” says Kraus. With further analysis of the artifacts and where they were found, she hopes to discover how slave life may have changed over the decades that the site was occupied.

Then she beckons to the back, smiling: “Our pride and joy!” There, wrapped gingerly in Ace bandages and foam, packed in wooden crates, are two urns found in a Site 1 trench dug during UXO clearance. They’re about two feet tall, brown, and coated in resin, and they look like bombs—which is what Van Den Bergh was told when she took one to the hospital for x-rays. They also resemble the urn Nitta found with bones. Van Den Bergh’s pots are stuffed with soil, too fragile to empty, but the x-rays revealed a possible bone fragment inside. Someday, she’ll figure a way to get at the contents.

Then she beckons to the back, smiling: “Our pride and joy!” There, wrapped gingerly in Ace bandages and foam, packed in wooden crates, are two urns found in a Site 1 trench dug during UXO clearance. They’re about two feet tall, brown, and coated in resin, and they look like bombs—which is what Van Den Bergh was told when she took one to the hospital for x-rays. They also resemble the urn Nitta found with bones. Van Den Bergh’s pots are stuffed with soil, too fragile to empty, but the x-rays revealed a possible bone fragment inside. Someday, she’ll figure a way to get at the contents.

“The Cherokee were trying to play by American rules,” says archaeologist Lance Greene, who worked with Riggs at UNC and now works at the Fort Armistead dig. “They were forming their own national government. A large part of the population had converted to Christianity. They sang Christian hymns as they were marching. There’s still an image of savage Indians living in tepees, but maybe the Cherokee, more than anybody, made an attempt [to acculturate]. But ultimately it failed.”

“The Cherokee were trying to play by American rules,” says archaeologist Lance Greene, who worked with Riggs at UNC and now works at the Fort Armistead dig. “They were forming their own national government. A large part of the population had converted to Christianity. They sang Christian hymns as they were marching. There’s still an image of savage Indians living in tepees, but maybe the Cherokee, more than anybody, made an attempt [to acculturate]. But ultimately it failed.”

The excavation and study of the site of Fort Armistead is beginning to flesh out the story of those who left. Now, the Cherokee, whose capital is Tahlequah in eastern Oklahoma, number some 300,000—comprising the United States’ second largest tribal nation. But the small band of Cherokee who stayed behind left a smaller but still significant legacy in southern Appalachia. It is estimated that about 400 Cherokee remained in North Carolina after the others were removed. They hid in the mountains where, unable to trade publicly, they found ways to survive by cooperating with one another. They often lived together in homesteads, and the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, which today numbers about 10,000, descends from residents of those homesteads.

The excavation and study of the site of Fort Armistead is beginning to flesh out the story of those who left. Now, the Cherokee, whose capital is Tahlequah in eastern Oklahoma, number some 300,000—comprising the United States’ second largest tribal nation. But the small band of Cherokee who stayed behind left a smaller but still significant legacy in southern Appalachia. It is estimated that about 400 Cherokee remained in North Carolina after the others were removed. They hid in the mountains where, unable to trade publicly, they found ways to survive by cooperating with one another. They often lived together in homesteads, and the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, which today numbers about 10,000, descends from residents of those homesteads. In 1987, Congress designated the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, about 2,200 miles across nine states. Fort Armistead is on the trail and is a remarkably fragile site. Hidden cameras, motion monitors, and a high-tech security system protect it from looters and unauthorized visitors. Among the visitors allowed at the site are Cherokee from Oklahoma, whose ancestors surely passed through the fort.

In 1987, Congress designated the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, about 2,200 miles across nine states. Fort Armistead is on the trail and is a remarkably fragile site. Hidden cameras, motion monitors, and a high-tech security system protect it from looters and unauthorized visitors. Among the visitors allowed at the site are Cherokee from Oklahoma, whose ancestors surely passed through the fort. Throughout the 19th century, excluding a brief moment in 1849 when Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi used it as a gun emplacement during his fight for Italian unification, families went to Monte Testaccio for picnics. Wine merchants discovered that Monte Testaccio’s interior was remarkably cool, and deep caves were cut into the sides to create storage cellars that were in use until about 100 years ago. Even into the 20th century, Romans went to pick arugula and hunt rabbits on Monte Testaccio, until it was closed to the public more than a decade ago at a time when people used the park to shoot heroin instead of bunnies. Throughout the millennia, Monte Testaccio was sometimes thought to be a dumping ground for debris from the emperor Nero’s A.D. 64 fire that destroyed much of the city, or for discarded funerary urns from the columbaria along the nearby Via Ostiense. The amphora sherds also provided a seemingly never-ending supply of tiles to refurbish the neighborhood and for visitors to take home as souvenirs.

Throughout the 19th century, excluding a brief moment in 1849 when Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi used it as a gun emplacement during his fight for Italian unification, families went to Monte Testaccio for picnics. Wine merchants discovered that Monte Testaccio’s interior was remarkably cool, and deep caves were cut into the sides to create storage cellars that were in use until about 100 years ago. Even into the 20th century, Romans went to pick arugula and hunt rabbits on Monte Testaccio, until it was closed to the public more than a decade ago at a time when people used the park to shoot heroin instead of bunnies. Throughout the millennia, Monte Testaccio was sometimes thought to be a dumping ground for debris from the emperor Nero’s A.D. 64 fire that destroyed much of the city, or for discarded funerary urns from the columbaria along the nearby Via Ostiense. The amphora sherds also provided a seemingly never-ending supply of tiles to refurbish the neighborhood and for visitors to take home as souvenirs. Finally, in the 1960s, Spanish archaeologist Emilio Rodriguez Almeida came to Testaccio to investigate how and when the hill was formed. He discovered, and Remesal’s current excavations have confirmed, that it grew in two distinct phases—an eastern section in use from the Augustan era through the mid-second century A.D., and a later one on the western side used extensively until A.D. 265, the latest consular date yet found. Remesal believes the sheer number of amphoras suggests Monte Testaccio had its own system of administration, although how this might have worked is unclear.

Finally, in the 1960s, Spanish archaeologist Emilio Rodriguez Almeida came to Testaccio to investigate how and when the hill was formed. He discovered, and Remesal’s current excavations have confirmed, that it grew in two distinct phases—an eastern section in use from the Augustan era through the mid-second century A.D., and a later one on the western side used extensively until A.D. 265, the latest consular date yet found. Remesal believes the sheer number of amphoras suggests Monte Testaccio had its own system of administration, although how this might have worked is unclear. Today, we covet Italian extra virgin olive oil, but in the Roman Empire the Italian peninsula couldn’t produce nearly enough to meet the population’s needs. In addition to being one of the staples of the Mediterranean diet, olive oil was also used for bathing, lighting, medicine, and as a mechanical lubricant. During the emperor Augustus’s reign, olive oil as well as other products, including garum (the fish sauce Romans used to flavor everything from steamed mussels to pear soufflés), metals, and wine began to come into Rome as tax payment in kind from the provinces of Hispania (roughly modern Spain), especially Baetica. Over the next several hundred years, Baetican oil imports continued to grow, reaching their peak at the end of the second century A.D. All of this oil came in amphoras. These inexpensive, durable, and often reusable containers (not to be confused with the expensive Greek painted fineware used as prizes in athletic games) were produced all over the empire in distinctive shapes from local materials. More than 85 percent of the amphoras found at Monte Testaccio are the type from Baetica known as Dressel 20, following Dressel’s classification system, which is still in use today. The other 15 percent came from North Africa, chiefly Libya and Tunisia, and are easily distinguished by thinner walls and a more slender shape. Amphoras were also used to transport other products, although the mountains of amphoras for wine or fish products (if they survive) have not been found.

Today, we covet Italian extra virgin olive oil, but in the Roman Empire the Italian peninsula couldn’t produce nearly enough to meet the population’s needs. In addition to being one of the staples of the Mediterranean diet, olive oil was also used for bathing, lighting, medicine, and as a mechanical lubricant. During the emperor Augustus’s reign, olive oil as well as other products, including garum (the fish sauce Romans used to flavor everything from steamed mussels to pear soufflés), metals, and wine began to come into Rome as tax payment in kind from the provinces of Hispania (roughly modern Spain), especially Baetica. Over the next several hundred years, Baetican oil imports continued to grow, reaching their peak at the end of the second century A.D. All of this oil came in amphoras. These inexpensive, durable, and often reusable containers (not to be confused with the expensive Greek painted fineware used as prizes in athletic games) were produced all over the empire in distinctive shapes from local materials. More than 85 percent of the amphoras found at Monte Testaccio are the type from Baetica known as Dressel 20, following Dressel’s classification system, which is still in use today. The other 15 percent came from North Africa, chiefly Libya and Tunisia, and are easily distinguished by thinner walls and a more slender shape. Amphoras were also used to transport other products, although the mountains of amphoras for wine or fish products (if they survive) have not been found. According to Roman pottery expert Theodore Peña of the Institute for European and Mediterranean Archaeology at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, “One of the keys to comprehending the Roman economy is to understand how the emperor supplied the people of Rome with basic foodstuffs.” This is where Monte Testaccio is again the best source. “In looking at these amphoras,” Peña continues, “we realize that this apparatus for handling oil and possibly grain was unique and went far beyond what the empire did for any other products.” Augustus, who became emperor in 27 B.C., knew that his power base came from two sources—the army and the plebs, or common people. He also understood that the needs of a growing population of Rome (between 600,000 and one million in the first century A.D.), along with a massive army stationed along frontiers from Spain to Syria, demanded a sophisticated and complex system to transport food and raw materials between Rome and its provinces. The emperor ensured the army’s support by paying and feeding it. He likewise bought the plebians’ loyalty by continuing the tradition, established in the mid-first century B.C., of providing them with access to free grain and by subsidizing the price of olive oil much like the current state-regulated price of tortillas in Mexico or baguettes in Tunisia. More than a century after Augustus, the Roman satirist Juvenal would give lasting expression to this populist approach in the famous line about the emperor giving the Romans “bread and circuses” in exchange for their freedom. To administer these needs, Augustus set up the praefectura annonae, or “prefect of the provisions,” an office whose function remains hotly debated. Some scholars believe the annona only handled the grain distribution for the plebs. But Remesal argues that the office served all of Rome’s inhabitants and dealt with many products, including olive oil. “From Augustus’s time, olive oil amphoras from Baetica are found at Monte Testaccio and as far as the northern borders of the empire, in the provinces of Brittania and Retia [parts of Austria and Germany],” he says. “I don’t think this could have happened without the emperor being directly involved.” But how far-reaching was this so-called “command economy,” the state-driven system controlled by the empire that brought olive oil to Rome and the amphoras to Monte Testaccio? University of Southampton archaeologist Simon Keay, who directs a major survey project at Portus, says, “The imperial finger is clearly on the pulse and they are very closely controlling and monitoring everything, but it’s not heavily bureaucratic. Rather, this is a system of small suppliers who are well controlled and monitored, not a system of great trade routes like other empires have had. It is uniquely Roman.”

According to Roman pottery expert Theodore Peña of the Institute for European and Mediterranean Archaeology at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, “One of the keys to comprehending the Roman economy is to understand how the emperor supplied the people of Rome with basic foodstuffs.” This is where Monte Testaccio is again the best source. “In looking at these amphoras,” Peña continues, “we realize that this apparatus for handling oil and possibly grain was unique and went far beyond what the empire did for any other products.” Augustus, who became emperor in 27 B.C., knew that his power base came from two sources—the army and the plebs, or common people. He also understood that the needs of a growing population of Rome (between 600,000 and one million in the first century A.D.), along with a massive army stationed along frontiers from Spain to Syria, demanded a sophisticated and complex system to transport food and raw materials between Rome and its provinces. The emperor ensured the army’s support by paying and feeding it. He likewise bought the plebians’ loyalty by continuing the tradition, established in the mid-first century B.C., of providing them with access to free grain and by subsidizing the price of olive oil much like the current state-regulated price of tortillas in Mexico or baguettes in Tunisia. More than a century after Augustus, the Roman satirist Juvenal would give lasting expression to this populist approach in the famous line about the emperor giving the Romans “bread and circuses” in exchange for their freedom. To administer these needs, Augustus set up the praefectura annonae, or “prefect of the provisions,” an office whose function remains hotly debated. Some scholars believe the annona only handled the grain distribution for the plebs. But Remesal argues that the office served all of Rome’s inhabitants and dealt with many products, including olive oil. “From Augustus’s time, olive oil amphoras from Baetica are found at Monte Testaccio and as far as the northern borders of the empire, in the provinces of Brittania and Retia [parts of Austria and Germany],” he says. “I don’t think this could have happened without the emperor being directly involved.” But how far-reaching was this so-called “command economy,” the state-driven system controlled by the empire that brought olive oil to Rome and the amphoras to Monte Testaccio? University of Southampton archaeologist Simon Keay, who directs a major survey project at Portus, says, “The imperial finger is clearly on the pulse and they are very closely controlling and monitoring everything, but it’s not heavily bureaucratic. Rather, this is a system of small suppliers who are well controlled and monitored, not a system of great trade routes like other empires have had. It is uniquely Roman.”