Online Exclusives

Erbil Revealed

By ANDREW LAWLER

Saturday, August 09, 2014

ARCHAEOLOGY contributing editor Andrew Lawler recently reported on the 6,000-year-history of the citadel of Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan. As the humanitarian and military crisis unfolds in Iraq, we present Lawler's story, which appears in ARCHAEOLOGY's September/October 2014 issue.

The 100-foot-high, oval-shaped citadel of Erbil towers high above the northern Mesopotamian plain, within sight of the Zagros Mountains that lead to the Iranian plateau. The massive mound, with its vertiginous man-made slope, built up by its inhabitants over at least the last 6,000 years, is the heart of what may be the world’s oldest continuously occupied settlement. At various times over its long history, the city has been a pilgrimage site dedicated to a great goddess, a prosperous trading center, a town on the frontier of several empires, and a rebel stronghold.

Yet despite its place as one of the ancient Near East’s most significant cities, Erbil’s past has been largely hidden. A dense concentration of nineteenth- and twentieth-century houses stands atop the mound, and these have long prevented archaeologists from exploring the city’s older layers. As a consequence, almost everything known about the metropolis—called Arbela in antiquity—has been cobbled together from a handful of ancient texts and artifacts unearthed at other sites. “We know Arbela existed, but without excavating the site, all else is a hypothesis,” says University of Cambridge archaeologist John MacGinnis.

Last year, for the first time, major excavations began on the north edge of the enormous hill, revealing the first traces of the fabled city. Ground-penetrating radar recently detected two large stone structures below the citadel’s center that may be the remains of a renowned temple dedicated to Ishtar, the goddess of love and war. There, according to ancient texts, Assyrian kings sought divine guidance, and Alexander the Great assumed the title of King of Asia in 331 B.C. Other new work includes the search for a massive fortification wall surrounding the ancient lower town and citadel, excavation of an impressive tomb just north of the citadel likely dating to the seventh century B.C., and examination of what lies under the modern city’s expanding suburbs. Taken together, these finds are beginning to provide a more complete picture not only of Arbela’s own story, but also of the growth of the first cities, the rise of the mighty Assyrian Empire, and the tenacity of an ethnically diverse urban center that has endured for more than six millennia. Located on a fertile plain that supports rain-fed agriculture, Erbil and its surrounds have, for thousands of years, been a regional breadbasket, a natural gateway to the east, and a key junction on the road connecting the Persian Gulf to the south with Anatolia to the north. Geography has been both the city’s blessing and curse in this perennially fractious region. Inhabitants fought repeated invasions by the soldiers of the Sumerian capital of Ur 4,000 years ago, witnessed three Roman emperors attack the Persians, and suffered the onslaught of Genghis Khan’s cavalry in the thirteenth century, the cannons of eighteenth-century Afghan warlords, and the wrath of Saddam Hussein’s tanks only 20 years ago. Yet, through thousands of years, the city survived, and even thrived, while other once-great cities such as Babylon and Nineveh crumbled.

Etruscan Finds at the "Necropolis of the Pub"

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, June 03, 2014

For the last three years, Italian archaeologists have been excavating a large Etruscan necropolis at the site of Vulci, 75 miles from Rome. Called (for reasons now obscure) the “Necropoli dell’Osteria,” or "Necropolis of the Pub," the large cemetery's most spectacular burial has been been dubbed "The Tomb of the Silver Hands," after the discovery of a pair of silver hands once adorned a wooden dummy. But the team has also uncovered dozens of other tombs containing remains and grave goods belonging to Etruscan nobles and common folk alike who lived in this region of Italy more than 2,500 years ago. Below is a selection of some of the most interesting artifacts from the site.

Among the many tombs in the necropolis, the team also found a small rectangular altar (left) that once held a jar containing cremated remains, and impressive tomb (right) filled with artifacts, including a pair of silver hands, that likely belonged to an Etruscan noble family.

Another wealthy tomb, excavated in 2012 near the “Tomb of the Silver Hands,” contained this spectacular stone figure of a sphinx.

Another wealthy tomb, excavated in 2012 near the “Tomb of the Silver Hands,” contained this spectacular stone figure of a sphinx.

The “Tomb of the Sphinx” also contained a blue faience scarab dating from sometime in the 25th or 26th Dynasty (746-525 B.C.). The Etruscans were particularly fond of Egyptian objects, many of which are found in tombs in this and other Etruscan tombs.

The “Tomb of the Sphinx” also contained a blue faience scarab dating from sometime in the 25th or 26th Dynasty (746-525 B.C.). The Etruscans were particularly fond of Egyptian objects, many of which are found in tombs in this and other Etruscan tombs.

Along with the tombs belonging to Etruscan nobility, archaeologists also found small family tombs like this one in the necropolis containing at least one, and possibly several, pottery jars in which the deceased cremated remains were buried.

Along with the tombs belonging to Etruscan nobility, archaeologists also found small family tombs like this one in the necropolis containing at least one, and possibly several, pottery jars in which the deceased cremated remains were buried.

Many of the artifacts, such as this painted terracotta architectural element from a well-decorated tomb in the necropolis, have been taken to a nearby lab to be reassembled, if possible, and conserved.

Many of the artifacts, such as this painted terracotta architectural element from a well-decorated tomb in the necropolis, have been taken to a nearby lab to be reassembled, if possible, and conserved.

Animal Mummy Coffins of Ancient Egypt

By ERIC A. POWELL

Thursday, January 30, 2014

In ancient Egypt, the practice of mummifying animals became widespread in the first millenium B.C. Until the advent of Christianity, visitors to temples could buy animal mummy bundles as offerings to the gods. Wealthier pilgrims could also splurge on elaborate coffins shaped as creatures to hold these mummies, which ancient Egyptians probably believed represented the souls of the gods. Along with the sale of animal mummies, the production of lavish bronze and wooden coffins must have been an important source of revenue for temples.

The coffins below illustrate the wide array of animal forms taken by Egyptian gods. They will accompany 30 newly rediscovered animal mummies in The Brooklyn Museum's traveling exhibit Soulful Creatures:Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. The exhibit's catalogue is available at gilesltd.com

Rock Art of Comanche Warriors

Wednesday, March 26, 2014

In New Mexico's Rio Grande Gorge, Barnard College archaeologist Severin Fowles and his team have recorded hundreds of panels of barely visible rock art left by Comanche around a basin known as the Vista Verde site. Groups of Comanche traveled to the area from the Great Plains during the early eighteenth century to take part in raiding or trading expeditions. Many of the panels depict warriors on horseback fighting other Native Americans or capturing horses. Unlike most rock art, which often represents timeless, ritually important subjects, these panels appear to depict real-life events, perhaps traced on the rocks by warriors eager to remind their fellow Comanche of their brave exploits. Below are tracings Fowles and his team made of some of the panels, which were scratched onto basalt boulders.

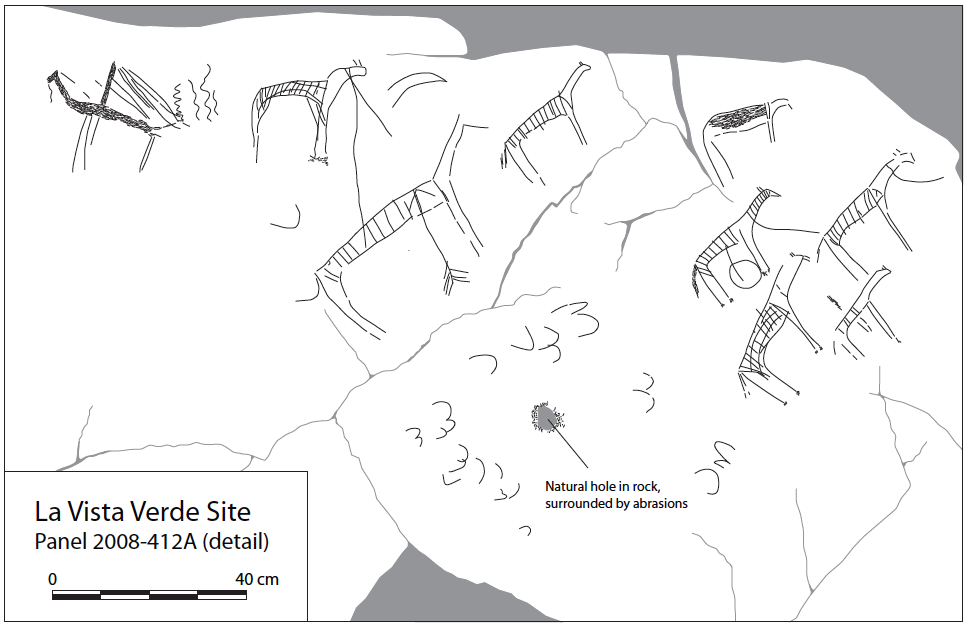

This detail of a panel at the Vista Verde site may depict a single Comanche engaged in feral horse raiding. In the upper left corner the warrior is visibly on horseback, with his headress flowing behind him. The wild horse to the immediate right appears to have a lasso around its neck, and the larger horse below may have an arrow lodged in its body. At the bottom of the panel are semi-circle abrasions around a natural hole in the rock. They may depict hoove prints around a watering hole, represented by the hole. According to tradition, one Comanche horse raiding tactic was to capture feral horses while they gathered around sources of water.

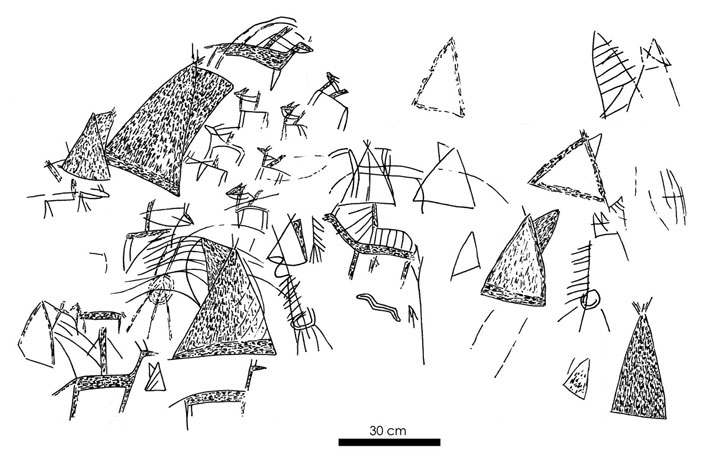

This panel appears to depict a Native American, probably Comanche, raid in progress at a tepee encampment. The mounted warrior on the lower left has lines connecting him with another figure. This could be a representation of the act of "counting coup," or physically touching your opponent in battle without a weapon, which was considered the greatest act of bravery a Plains Indian could commit in battle. The Comanche were known as fierce warriors. The very word "Comanche" comes from a Ute term that translates as "anyone who wants to fight me all the time." Outside some of the teppees in this panel are circles on top of three or four lines. These probably represent personal shields, which Plains Indians rested on tripods outside their tepees to represent their owners.

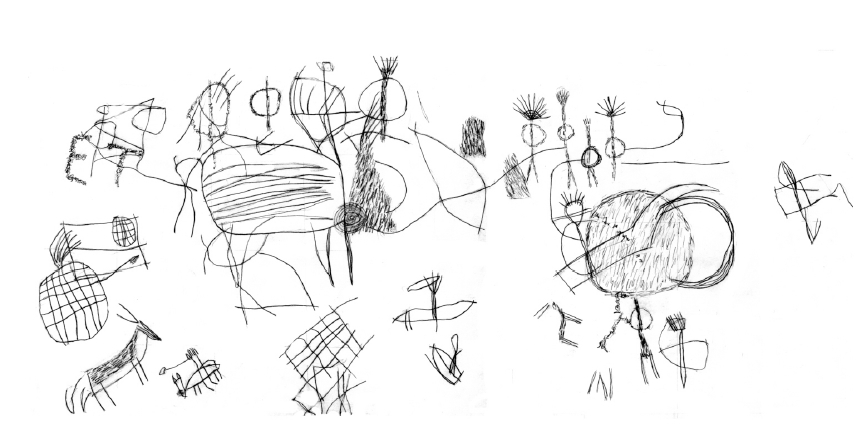

Reminiscent of a football coach’s chalkboard diagramming plays this rock art panel depicts several different warriors on foot wearing headdresses and bearing shields. To the upper left the initials “E.T.” are visible, a reminder that cowboys, herders, and modern tourists have left their own graffiti on the same boulders used by the Comanche. Lines likely depicting the act of counting coup connect several of the warriors on this panel.

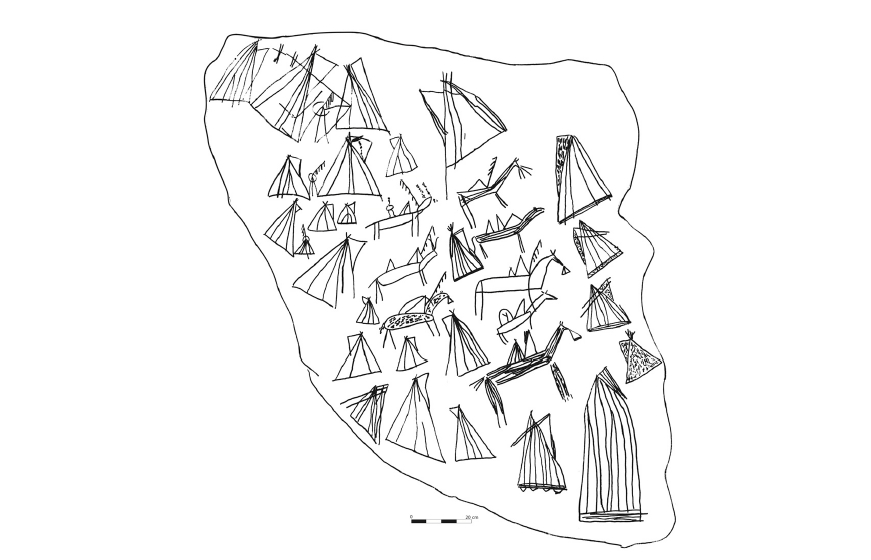

Some two-dozen tepees are depicted on this boulder, which seems to show Comanche warriors mounting their horses, perhaps in preparation for a raid or trading mission to a nearby settlement. Depictions of tepees are one of the most common scenes found around the Vista Verde site, and it’s possible this panel is a sketch of the site itself.

|

Feature Article:

|

Searching for the Comanche Empire

|

Animal Mummy Coffins of Ancient Egypt

Thursday, January 23, 2014

In ancient Egypt, the practice of mummifying animals became widespread in the first millenium B.C. Until the advent of Christianity, visitors to temples could buy animal mummy bundles as offerings to the gods. Wealthier pilgrims could also splurge on elaborate coffins shaped as creatures to hold these mummies, which ancient Egyptians probably believed represented the souls of the gods. Along with the sale of animal mummies, the production of lavish bronze and wooden coffins must have been an important source of revenue for temples.

The coffins below illustrate the wide array of animal forms taken by Egyptian gods. They will accompany 30 newly rediscovered animal mummies in The Brooklyn Museum's traveling exhibit Soulful Creatures:Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. The exhibit's catalogue is available at gilesltd.com.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

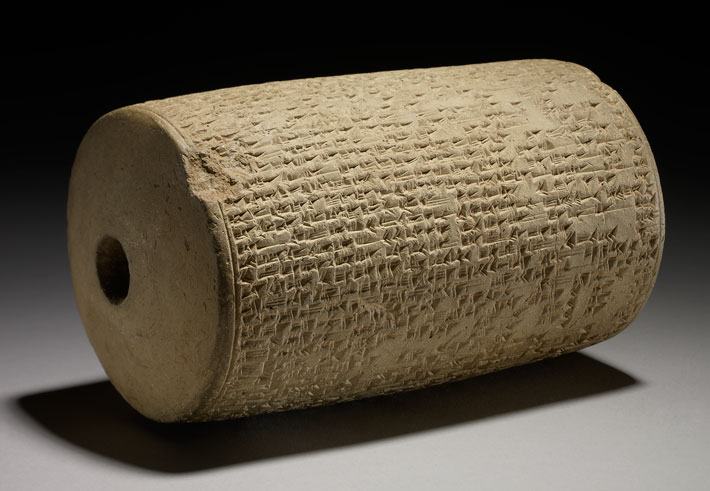

Today Erbil is the capital of Iraq’s autonomous province of Kurdistan. The citadel remains at the heart of a thriving city with a population of 1.3 million, made up mostly of Kurds, and a boomtown economy, thanks to a combination of tight security and oil wealth. During the twentieth century, the high mound fell into disrepair as refugees from the region’s conflicts replaced the town’s established wealthy families, who moved to more spacious accommodations in the lower town and suburbs below. The refugees have since moved to new settlements, and efforts are currently under way to renovate the deteriorating nineteenth- and twentieth-century mudbrick dwellings and twisting, narrow alleys. A textile museum opened in a restored, grand, century-old mansion in early 2014, and work rebuilding the adjacent nineteenth-century Ottoman gate, which sits on much more ancient foundations, is nearing completion. The conservation work is also giving archaeologists the chance to dig into the mound—which has just been declared a World Heritage Site—once so wholly inaccessible. “Erbil has been largely neglected, and we know so little,” says archaeologist Karel Novacek of the University of West Bohemia in the Czech Republic, who conducted the first limited excavations on the citadel in 2006. Extensive long-term excavations are not feasible in Erbil. Nevertheless, Novacek, MacGinnis, their Iraqi colleagues, and archaeologists from Italy, France, Greece, Germany, and the United States, are using old aerial photographs, Cold War satellite imagery, and archives of ancient cuneiform tablets to pinpoint the best spots to dig in order to take advantage of this first real opportunity to examine Erbil’s past. Although the citadel has played an important role in the Near East for millennia, knowledge of the site has been remarkably limited because so little archaeology has been done there and in the surrounding area. Only a few pieces of 5,000-year-old pottery found on the citadel attest to the existence of ancient Arbela. And although the greatest quantity of information about the city’s appearance, inhabitants, and role in the region derives from the Assyrian period, almost all of the evidence we have comes from texts and artifacts found at other sites.

Today Erbil is the capital of Iraq’s autonomous province of Kurdistan. The citadel remains at the heart of a thriving city with a population of 1.3 million, made up mostly of Kurds, and a boomtown economy, thanks to a combination of tight security and oil wealth. During the twentieth century, the high mound fell into disrepair as refugees from the region’s conflicts replaced the town’s established wealthy families, who moved to more spacious accommodations in the lower town and suburbs below. The refugees have since moved to new settlements, and efforts are currently under way to renovate the deteriorating nineteenth- and twentieth-century mudbrick dwellings and twisting, narrow alleys. A textile museum opened in a restored, grand, century-old mansion in early 2014, and work rebuilding the adjacent nineteenth-century Ottoman gate, which sits on much more ancient foundations, is nearing completion. The conservation work is also giving archaeologists the chance to dig into the mound—which has just been declared a World Heritage Site—once so wholly inaccessible. “Erbil has been largely neglected, and we know so little,” says archaeologist Karel Novacek of the University of West Bohemia in the Czech Republic, who conducted the first limited excavations on the citadel in 2006. Extensive long-term excavations are not feasible in Erbil. Nevertheless, Novacek, MacGinnis, their Iraqi colleagues, and archaeologists from Italy, France, Greece, Germany, and the United States, are using old aerial photographs, Cold War satellite imagery, and archives of ancient cuneiform tablets to pinpoint the best spots to dig in order to take advantage of this first real opportunity to examine Erbil’s past. Although the citadel has played an important role in the Near East for millennia, knowledge of the site has been remarkably limited because so little archaeology has been done there and in the surrounding area. Only a few pieces of 5,000-year-old pottery found on the citadel attest to the existence of ancient Arbela. And although the greatest quantity of information about the city’s appearance, inhabitants, and role in the region derives from the Assyrian period, almost all of the evidence we have comes from texts and artifacts found at other sites.

At the core of Arbela’s religious, political, and economic life in this period was the Egasankalamma, or “House of the Lady of the Land.” Assyrian texts mention the temple, dedicated to Ishtar, as early as the thirteenth century B.C., though its foundations likely rest on even older sacred structures. In Mesopotamian theology Ishtar was the goddess of love, fertility, and war. Martti Nissinen of the University of Helsinki has closely examined the 265 references to the goddess in Assyrian texts, and he suggests that the roots of this version of Ishtar may lay deep in the ancient Hurrian pantheon.

At the core of Arbela’s religious, political, and economic life in this period was the Egasankalamma, or “House of the Lady of the Land.” Assyrian texts mention the temple, dedicated to Ishtar, as early as the thirteenth century B.C., though its foundations likely rest on even older sacred structures. In Mesopotamian theology Ishtar was the goddess of love, fertility, and war. Martti Nissinen of the University of Helsinki has closely examined the 265 references to the goddess in Assyrian texts, and he suggests that the roots of this version of Ishtar may lay deep in the ancient Hurrian pantheon. Under the Assyrians, Arbela was a cosmopolitan gathering place for foreign ambassadors coming from the east. “Tribute enters it from all the world!” says Ashurbanipal in one text. A governor oversaw the city’s administration from a sumptuous citadel palace where taxpayers brought copper and cattle, pomegranates, pistachios, grain, and grapes. Arbela’s own inhabitants were a diverse mix that likely included those forcibly resettled by the Assyrian state, as well as immigrants, merchants, and others seeking opportunity in a city that rivaled the Assyrian capitals in stature. “Arbela at this time was a multiethnic state,” says Dishad Marf, a scholar at the Netherlands’ Leiden University. Names of its citizens found in Assyrian texts are Babylonian, Assyrian, Hurrian, Aramain, Shubrian, Scythian, and Palestinian.

Under the Assyrians, Arbela was a cosmopolitan gathering place for foreign ambassadors coming from the east. “Tribute enters it from all the world!” says Ashurbanipal in one text. A governor oversaw the city’s administration from a sumptuous citadel palace where taxpayers brought copper and cattle, pomegranates, pistachios, grain, and grapes. Arbela’s own inhabitants were a diverse mix that likely included those forcibly resettled by the Assyrian state, as well as immigrants, merchants, and others seeking opportunity in a city that rivaled the Assyrian capitals in stature. “Arbela at this time was a multiethnic state,” says Dishad Marf, a scholar at the Netherlands’ Leiden University. Names of its citizens found in Assyrian texts are Babylonian, Assyrian, Hurrian, Aramain, Shubrian, Scythian, and Palestinian. After so many centuries of regional domination, the Assyrians’ fall was sudden and swift—and Arbela proved to be the sole surviving major settlement. A coalition of Babylonians and Medes, a nomadic people who lived on the Iranian plateau, destroyed the Assyrian capitals in 612 B.C. and scattered their once-feared armies. Arbela was spared, perhaps because its population was in large part non-Assyrian and sympathetic to the new conquerors. The Medes, who may be the ancestors of today’s Kurds, likely took control of the city, which was still intact a century later when the Persian king Darius I, third king of the Achaemenid Empire, impaled a rebel on Arbela’s ramparts—a scene recorded in an inscription carved on a western Iranian cliff around 500 B.C.

After so many centuries of regional domination, the Assyrians’ fall was sudden and swift—and Arbela proved to be the sole surviving major settlement. A coalition of Babylonians and Medes, a nomadic people who lived on the Iranian plateau, destroyed the Assyrian capitals in 612 B.C. and scattered their once-feared armies. Arbela was spared, perhaps because its population was in large part non-Assyrian and sympathetic to the new conquerors. The Medes, who may be the ancestors of today’s Kurds, likely took control of the city, which was still intact a century later when the Persian king Darius I, third king of the Achaemenid Empire, impaled a rebel on Arbela’s ramparts—a scene recorded in an inscription carved on a western Iranian cliff around 500 B.C. Novacek, meanwhile, has turned his attention to the ancient city that grew up in the citadel’s shadow. “The lower town, which has been barely investigated, is the key to understanding the city’s dynamics,” he says. “Digging there requires a different approach.” Today Erbil’s thickly settled downtown, in fact, hides traces of the ancient site. Novacek is using British Royal Air Force aerial photos taken in the 1950s and American spy satellite images from the 1960s Corona program to look for remnants of the ancient city that survived into at least the middle of the twentieth century. He has found faint outlines of two sets of fortifications. One of these is a modest system probably dating from the medieval era, while the second is a much larger set of structures that likely dates to some time in the Assyrian period, and had been bulldozed to make way for the modern town in the 1960s.

Novacek, meanwhile, has turned his attention to the ancient city that grew up in the citadel’s shadow. “The lower town, which has been barely investigated, is the key to understanding the city’s dynamics,” he says. “Digging there requires a different approach.” Today Erbil’s thickly settled downtown, in fact, hides traces of the ancient site. Novacek is using British Royal Air Force aerial photos taken in the 1950s and American spy satellite images from the 1960s Corona program to look for remnants of the ancient city that survived into at least the middle of the twentieth century. He has found faint outlines of two sets of fortifications. One of these is a modest system probably dating from the medieval era, while the second is a much larger set of structures that likely dates to some time in the Assyrian period, and had been bulldozed to make way for the modern town in the 1960s. The earlier fortifications include a 60-foot-thick wall that likely had a defensive slope and a moat. The city’s formidable construction, says Novacek, resembles that found at Nineveh and Assur, and places it “unambiguously among Mesopotamian mega-cities.” The layout differs from that in other Assyrian cities, where the walls were rectangular, with a citadel as part of the protective fortifications. Arbela, however, had an irregular round wall entirely enclosing both the citadel and the lower town. That design is more typical of ancient southern Mesopotamian cities such as Ur and Uruk—a hint, Novacek says, of Erbil’s ancient urban heritage. “This conjecture desperately needs empirical verification,” he cautions. Yet, if it can be proven, ancient Arbela might rank among the earliest urban areas and challenge the idea that urbanism began solely in southern Mesopotamia.

The earlier fortifications include a 60-foot-thick wall that likely had a defensive slope and a moat. The city’s formidable construction, says Novacek, resembles that found at Nineveh and Assur, and places it “unambiguously among Mesopotamian mega-cities.” The layout differs from that in other Assyrian cities, where the walls were rectangular, with a citadel as part of the protective fortifications. Arbela, however, had an irregular round wall entirely enclosing both the citadel and the lower town. That design is more typical of ancient southern Mesopotamian cities such as Ur and Uruk—a hint, Novacek says, of Erbil’s ancient urban heritage. “This conjecture desperately needs empirical verification,” he cautions. Yet, if it can be proven, ancient Arbela might rank among the earliest urban areas and challenge the idea that urbanism began solely in southern Mesopotamia. The ongoing research of the teams now working in the city is starting to create an archaeological picture of life in Erbil and its environs over the course of millennia. After the Assyrians, Persians, and Greeks were gone, the city went on to serve as a key eastern outpost on the Roman frontier, and was briefly the capital of the Roman province of Assyria. Later it was home to flourishing Christian and Zoroastrian communities under Persian Sasanian rule until the arrival of Islam in the seventh century A.D. Though the city escaped destruction by the Mongols in the thirteenth century—its leaders wisely negotiated surrender—Erbil subsequently slipped into obscurity. When Western explorers arrived in the eighteenth century they dismissed the place as a muddy and decrepit settlement of medieval origin. While Kurdistan’s isolation under the latter part of Saddam Hussein’s reign placed the area off-limits to most outsiders, in the post-Saddam era, Erbil has been set to play an important role in the region. Conflict, however, threatens again. Amid the archaeologists’ trenches and the mounds of construction materials destined for use in the citadel’s conservation, one family still lives on Erbil’s high mound, near the ancient citadel gate, preserving the city’s claim as the oldest continuously settled place on Earth.

The ongoing research of the teams now working in the city is starting to create an archaeological picture of life in Erbil and its environs over the course of millennia. After the Assyrians, Persians, and Greeks were gone, the city went on to serve as a key eastern outpost on the Roman frontier, and was briefly the capital of the Roman province of Assyria. Later it was home to flourishing Christian and Zoroastrian communities under Persian Sasanian rule until the arrival of Islam in the seventh century A.D. Though the city escaped destruction by the Mongols in the thirteenth century—its leaders wisely negotiated surrender—Erbil subsequently slipped into obscurity. When Western explorers arrived in the eighteenth century they dismissed the place as a muddy and decrepit settlement of medieval origin. While Kurdistan’s isolation under the latter part of Saddam Hussein’s reign placed the area off-limits to most outsiders, in the post-Saddam era, Erbil has been set to play an important role in the region. Conflict, however, threatens again. Amid the archaeologists’ trenches and the mounds of construction materials destined for use in the citadel’s conservation, one family still lives on Erbil’s high mound, near the ancient citadel gate, preserving the city’s claim as the oldest continuously settled place on Earth.