Lost Tombs

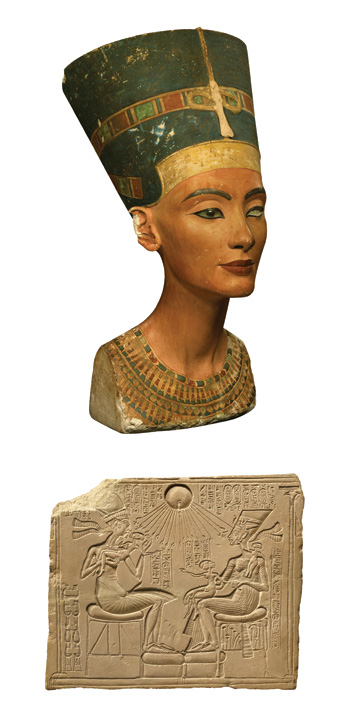

Nefertiti, Great Royal Wife and Queen of Egypt

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

In the 1880s, residents living near the ancient Egyptian city of Amarna discovered a large multichambered rock-cut tomb. It was one of many such tombs at Amarna, but its impressive size distinguished it from the others. Unfortunately, the tomb, called Amarna 26, has been badly damaged by looters, weather, and time, and many of the most significant artifacts were removed at some point, either in antiquity or more recently. Relatively little of the tomb’s fragile decoration is intact. Nevertheless, enough inscribed artifacts do survive—including more than 200 shabti figurines, an alabaster chest, and two large granite sarcophagi—that archaeologists are reasonably certain the tomb, also called the Royal Tomb, belonged to the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten and his daughter Meketaten.

In the 1880s, residents living near the ancient Egyptian city of Amarna discovered a large multichambered rock-cut tomb. It was one of many such tombs at Amarna, but its impressive size distinguished it from the others. Unfortunately, the tomb, called Amarna 26, has been badly damaged by looters, weather, and time, and many of the most significant artifacts were removed at some point, either in antiquity or more recently. Relatively little of the tomb’s fragile decoration is intact. Nevertheless, enough inscribed artifacts do survive—including more than 200 shabti figurines, an alabaster chest, and two large granite sarcophagi—that archaeologists are reasonably certain the tomb, also called the Royal Tomb, belonged to the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten and his daughter Meketaten.

But the Royal Tomb also contains a third, unfinished chamber whose royal resident is unknown.Could it perhaps be the tomb of Akhenaten’s wife, Nefertiti? Egyptologist Marc Gabolde of Paul Valéry University, who has been searching for Nefertiti’s tomb, thinks so. “I now believe that Nefertiti died a few months before Akhenaten and was buried at Amarna, despite the fact that her suite in the Royal Tomb was unfinished.” But at least one other scholar is less certain. “I do not think it is likely that she was buried in Amarna,” says archaeologist Barry Kemp of the University of Cambridge, director of the Amarna Project. “Or, at least, nothing found in the tomb suggests that it had housed burial equipment for her,” Kemp adds. “She could have been buried at Thebes, or on the now utterly robbed necropolis at Gurob; or she could have been taken back to her home city of Akhmim and buried in the ancestral cemetery there. We may never know.”

Alexander the Great, King of Macedon

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

When St. John Chrysostom visited Alexandria in A.D. 400, he asked to see Alexander’s burial place, adding, “His tomb even his own people know not.” It is a question that continues to be asked now, 1,613 years later. Alexander died in the Mesopotamian capital of Babylon in 323 B.C., perhaps from poisoning, malaria, typhoid, West Nile fever, or grief over the death of his best friend, Hephaestion. For two years, Alexander’s mummified remains, housed in a golden sarcophagus, lay in state, a pawn in the game of royal succession. Finally, it was decided that Alexander would be buried in Greece at Aegae, the first capital of the Macedonian kings. But according to ancient sources, his hearse was hijacked near Damascus and the corpse taken to Egypt, first to Memphis, and, some time between 298 and 283 B.C., to Alexandria, the city he had founded and named after himself.

There, Alexander was interred in at least two tombs in different locations, the more notable of which ancient authors, such as Strabo, Plutarch, and Pausanias, identify as a mausoleum called the Soma, meaning “body” in ancient Greek. The Soma was repeatedly robbed—the golden sarcophagus was melted down and replaced with one made of glass or crystal. Even Cleopatra took gold from the tomb to pay for her war against Octavian (soon to be the emperor Augustus). There were subsequent visits to the tomb by numerous Roman emperors and then, beginning in A.D. 360, a series of events that included warfare, riots, an earthquake, and a tsunami, threatened—or perhaps destroyed—the tomb by the time of Chrysostom’s visit. From that point on, Alexander’s tomb can be considered lost. And despite centuries of relentless searching by archaeologists, authors, and amateurs, it remains so.

There, Alexander was interred in at least two tombs in different locations, the more notable of which ancient authors, such as Strabo, Plutarch, and Pausanias, identify as a mausoleum called the Soma, meaning “body” in ancient Greek. The Soma was repeatedly robbed—the golden sarcophagus was melted down and replaced with one made of glass or crystal. Even Cleopatra took gold from the tomb to pay for her war against Octavian (soon to be the emperor Augustus). There were subsequent visits to the tomb by numerous Roman emperors and then, beginning in A.D. 360, a series of events that included warfare, riots, an earthquake, and a tsunami, threatened—or perhaps destroyed—the tomb by the time of Chrysostom’s visit. From that point on, Alexander’s tomb can be considered lost. And despite centuries of relentless searching by archaeologists, authors, and amateurs, it remains so.

Alfred, King of Wessex

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

He was the first king of “all the English” and the only English king to be called “the Great.” When Alfred died at the age of 50, after a remarkable reign, he was laid to rest at Winchester’s Old Minster. Just two years later, Alfred’s son Edward began construction of a new minster next to the old one, and his father’s remains were moved to a new mausoleum there in 903. The king was only to rest there for two centuries. In 1110, his body was transported to the new Hyde Abbey, along with those of his wife and son, just outside the city walls. But this too was not to be Alfred’s final resting place. At some point after the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII, the monarch’s tomb may have been ransacked and the bones moved again, this time to a simple grave at St. Bartholomew’s Parish Church, which had been built partly on the site of the destroyed abbey.

He was the first king of “all the English” and the only English king to be called “the Great.” When Alfred died at the age of 50, after a remarkable reign, he was laid to rest at Winchester’s Old Minster. Just two years later, Alfred’s son Edward began construction of a new minster next to the old one, and his father’s remains were moved to a new mausoleum there in 903. The king was only to rest there for two centuries. In 1110, his body was transported to the new Hyde Abbey, along with those of his wife and son, just outside the city walls. But this too was not to be Alfred’s final resting place. At some point after the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII, the monarch’s tomb may have been ransacked and the bones moved again, this time to a simple grave at St. Bartholomew’s Parish Church, which had been built partly on the site of the destroyed abbey.

There have been periodic attempts to find Alfred’s tomb for more than 100 years: The first of these was led by a local antiquary in the nineteenth century, and the second during an excavation commissioned by the Winchester City Council more than a decade ago. No tombs, and only one human bone, which turned out to be from a female, were found during either effort. And there are those who believe the king’s bones were never reburied, but rather scattered by eighteenth-century construction work on the site of the abbey. There is an increased fascination with the remains of English monarchs after the recent identification of Richard III, so last March the diocese of St. Bartholomew commissioned three archaeologists to excavate an unmarked grave in the churchyard, thought perhaps to be the location of Alfred’s last burial, in order to protect the remains from possible vandalism or theft. For now the exhumed bones lie in a secure location, awaiting further study—and the final resting place of England’s first and greatest king remains uncertain.

Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

Though her moment in time was short, Boudicca is a towering figure of British history. As the leader of a large popular uprising in A.D. 60, she has been lauded for her defense of Britain from excessive taxation, property loss, and enslavement under the Roman Empire. And the ancient Roman historian Cassius Dio’s description of the Celtic queen has captured imaginations for millennia:

Though her moment in time was short, Boudicca is a towering figure of British history. As the leader of a large popular uprising in A.D. 60, she has been lauded for her defense of Britain from excessive taxation, property loss, and enslavement under the Roman Empire. And the ancient Roman historian Cassius Dio’s description of the Celtic queen has captured imaginations for millennia:

In stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce, and her voice was harsh; a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips, around her neck was a large golden necklace and she wore a tunic of many colors.

It is thought that, fearing capture and torture, Boudicca fled home to her kingdom in southern Britain after the final battle, during which her forces were massacred. Although Dio describes a lavish burial, the locations of neither her death nor the battle are known.

Fantastic and unsubstantiated rumors profess that the queen is buried under platform 8, 9, or 10 at London’s King’s Cross railway station, yet no traces of her have been found in this or any other location. According to Mike Heyworth, director of the Council for British Archaeology, even if remains are found that might be Boudicca’s, it would be challenging to be certain because of the lack of physical evidence that would prove it conclusively. Further, says archaeologist Richard Hingley of Durham University, if the queen died in battle, the remains would probably have been cleared away along with weapons and debris, leaving little left to find. “It is unlikely that Boudicca would have had a burial monument,” says Hingley. “Most Iron Age people in this region were disposed of in ways that do not show up in the archaeological record.” However, he adds, that has not stopped “a variety of people actively looking for the site.”

Genghis Khan, Founder of the Mongol Empire

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

By the time he died in 1227, Genghis Khan had gone from being cast out of a minor Mongol tribe to ruling the largest contiguous empire in history, stretching from China to the Caspian Sea. Today, Genghis Khan is still worshipped as a national hero of Mongolia, but the location of his burial is shrouded in mystery. Chinese and Persian historical sources suggest Genghis died during a campaign in China, possibly falling off his horse during a hunt, and that his sons took his body back to Mongolia for burial. A number of accounts agree that his coffin was placed in a pit and that the ground above was restored to its original appearance to conceal it. According to one source, 10,000 horsemen trampled the ground above it to make it even. Beginning in the 1960s, several expeditions have searched for the grave, but without success. Today, many scholars agree that Genghis was likely interred somewhere in the Khentii mountain range of northeastern Mongolia, not far from his birthplace.

By the time he died in 1227, Genghis Khan had gone from being cast out of a minor Mongol tribe to ruling the largest contiguous empire in history, stretching from China to the Caspian Sea. Today, Genghis Khan is still worshipped as a national hero of Mongolia, but the location of his burial is shrouded in mystery. Chinese and Persian historical sources suggest Genghis died during a campaign in China, possibly falling off his horse during a hunt, and that his sons took his body back to Mongolia for burial. A number of accounts agree that his coffin was placed in a pit and that the ground above was restored to its original appearance to conceal it. According to one source, 10,000 horsemen trampled the ground above it to make it even. Beginning in the 1960s, several expeditions have searched for the grave, but without success. Today, many scholars agree that Genghis was likely interred somewhere in the Khentii mountain range of northeastern Mongolia, not far from his birthplace.

Now an international effort of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences, the University of California, San Diego, (UCSD) and the National Geographic Society is using remote-sensing techniques to search for the tomb. The team hopes finding it will close a gap in the historical record for Mongolians and the world at large. “He transformed the planet,” says UCSD engineer Albert Lin, who helped start the project in 2009. “But there isn’t even a painting of him by his own people. There’s a missing physical element to his legacy, and just finding the location of his burial would give Mongolians an important link to him.” The Mongolian government could announce the team’s preliminary findings later this year.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement