Lost Tombs

Atahualpa, Last Inca Emperor

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

After fighting a bloody civil war against his brother, the prince Atahualpa emerged as the sole leader of the Inca in 1532. But his reign was short-lived. While traveling to the Inca capital Cuzco to claim his throne, Atahualpa was seized at the town of Cajamarca by a small band of Spanish troops led by Francisco Pizarro. Legend has it that Atahualpa offered to fill a room with gold and silver in exchange for his release, but Pizarro had him executed in 1533. The Spanish gave Atahualpa a Christian burial in Cajamarca, but numerous accounts suggest his body was exhumed by his followers and mummified.

After fighting a bloody civil war against his brother, the prince Atahualpa emerged as the sole leader of the Inca in 1532. But his reign was short-lived. While traveling to the Inca capital Cuzco to claim his throne, Atahualpa was seized at the town of Cajamarca by a small band of Spanish troops led by Francisco Pizarro. Legend has it that Atahualpa offered to fill a room with gold and silver in exchange for his release, but Pizarro had him executed in 1533. The Spanish gave Atahualpa a Christian burial in Cajamarca, but numerous accounts suggest his body was exhumed by his followers and mummified.

Ecuadorian historian Tamara Estupiñán of the French Institute of Andean Studies has spent more than a decade examining records from the period. Based on her analysis of the documents, she thinks one of Atahualpa’s generals, Rumiñahui, brought the emperor’s mummy to what is now Ecuador for safekeeping. She pinpoints the recently rediscovered site of Maiqui-Machay as Atahualpa’s final resting place. David Brown, a research fellow at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, is one of a group of researchers who have conducted recent fieldwork at the site, which was a small rural settlement occupied for several centuries before the Inca. “I think the evidence gathered by Tamara is certainly suggestive and points to the possibility that the mummy could have been carried there,” says Brown. “But the archaeology is lagging behind.” It’s unlikely that Atahualpa’s mummy survived the centuries, but other evidence from the Inca occupation of Maiqui-Machay could emerge to support Estupiñán’s bold thesis. “It remains for archaeologists to test through careful fieldwork,” says Brown.

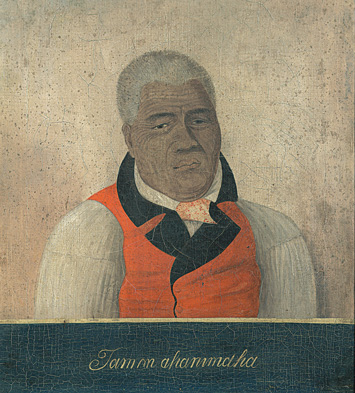

Kamehameha I, King of Hawaii

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

The morning star alone knows where Kamehameha’s bones are guarded. Despite the words of the Hawaiian proverb, people have speculated about the burial place of Hawaii’s first king ever since he died in 1819. Most can agree that his trusted lieutenants Ho’olulu and Hoapili took his bones and left them in a sacred burial cave whose location they kept secret. According to nineteenth-century historian David Malo, the two were strict adherents of the ancient Hawaiian concept of kahu, or the responsibility to guard idols or sacred things. “It is owing to the fidelity of the kahu that the hiding place of the great Kamehameha’s bones is to this day a profound secret,” wrote Malo in 1839.

The morning star alone knows where Kamehameha’s bones are guarded. Despite the words of the Hawaiian proverb, people have speculated about the burial place of Hawaii’s first king ever since he died in 1819. Most can agree that his trusted lieutenants Ho’olulu and Hoapili took his bones and left them in a sacred burial cave whose location they kept secret. According to nineteenth-century historian David Malo, the two were strict adherents of the ancient Hawaiian concept of kahu, or the responsibility to guard idols or sacred things. “It is owing to the fidelity of the kahu that the hiding place of the great Kamehameha’s bones is to this day a profound secret,” wrote Malo in 1839.

Some Hawaiians believe Kamehameha is buried at the royal palace of Moku’ula, in Maui, the residence of King Kamehameha III from 1837 to 1845, and the site of a royal burial ground. According to legend, Kamehameha I may lie under Moku’ula in the grotto of a half-dragon, half-woman named Kihawahine. Others think his remains are in a cave in Maui’s Iao Valley, where many great Hawaiian chiefs are interred. In the late nineteenth century, the last Hawaiian king, David Kalakaua, who was passionate about Hawaiian history and culture—he is known for revitalizing the hula—became interested in finding Kamehameha’s remains. He is said to have ordered two sets of bones removed from a burial cave on the island of Hawaii and interred in the Royal Mausoleum in Oahu, believing one of them to have been Kamehameha’s. But information about those remains is sketchy, and the power of kahu will probably ensure Kamehameha’s bones will never be disturbed.

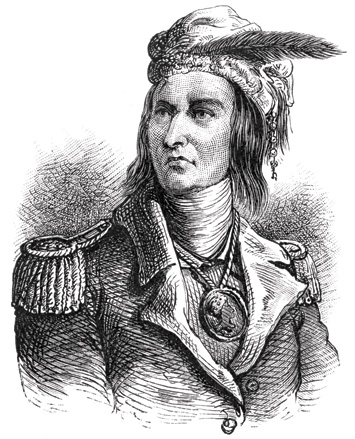

Tecumseh, Shawnee Leader

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

Throughout history in many cultures, preserving the physical remains of great figures has been considered vital for religious, cultural, or political reasons. Many Native Americans don’t share that outlook. The burial of Shawnee leader Tecumseh is a case in point. Tecumseh, whose name means “shooting star” or “panther in the sky,” led the Shawnee and a coalition of other native groups in resisting American settlement of the Ohio and Indiana territories in the early nineteenth century. He allied his forces with the English during the War of 1812 but was abandoned by them in 1813, at the Battle of the Thames in what is now Ontario. Refusing to retreat, Tecumseh died leading his outnumbered forces against American troops led by future president William Henry Harrison. According to eyewitnesses, Tecumseh’s slain body was taken up by his warriors, who buried him close to the battlefield.

Throughout history in many cultures, preserving the physical remains of great figures has been considered vital for religious, cultural, or political reasons. Many Native Americans don’t share that outlook. The burial of Shawnee leader Tecumseh is a case in point. Tecumseh, whose name means “shooting star” or “panther in the sky,” led the Shawnee and a coalition of other native groups in resisting American settlement of the Ohio and Indiana territories in the early nineteenth century. He allied his forces with the English during the War of 1812 but was abandoned by them in 1813, at the Battle of the Thames in what is now Ontario. Refusing to retreat, Tecumseh died leading his outnumbered forces against American troops led by future president William Henry Harrison. According to eyewitnesses, Tecumseh’s slain body was taken up by his warriors, who buried him close to the battlefield.

No record exists of the exact location of Tecumseh’s grave. But Ken Tankersley, a University of Cincinnati archaeologist who is an enrolled member of the Piqua Shawnee and sits on the tribe’s Council of Elders, says that isn’t important. “For indigenous people, and the Shawnee in particular, what’s important is for the dead to ‘make the journey,’ or allowing the body to decompose, creating nutrients in the soil, and thus allow the cycle of life to continue.” Tankersley notes that Shawnee will occasionally visit the battlefield and leave a tobacco offering. “We know where the battle was, and the whole battlefield is considered a sacred site, and that is close enough.” He predicts that protests would erupt if an archaeologist or anyone else ever tried to find Tecumseh’s remains. Even using noninvasive remote-sensing technology to locate the burial would be considered unacceptable, says Tankersley. “No one should ever go looking for Tecumseh.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement