Features

Tomb of the Vulture Lord

By ROGER ATWOOD

Monday, August 12, 2013

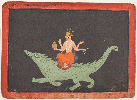

For 2,500 years, the Vulture Lord’s tomb lay hidden in the rugged highlands of southern Guatemala. In comparison to the soaring pyramids of other sites in the region, his burial monument was a fairly modest, 16-foot-high, grassy platform made of clay and cobblestones. But eight feet below its summit, at the bottom of a damp cavity uncovered after two years of meticulous excavation, archaeologists Christa Schieber and Miguel Orrego from Guatemala’s Cultural and Natural Heritage Office found hundreds of apple-green and blue jade beads. A few feet away were six skillfully made clay female figurines, one of which had a face that was old and wrinkled on one side, and fresh and young on the other side. Another had a tattoo design on its back. Nearby, an array of ceramic bowls lay jumbled about, suggesting they had once been piled with food offerings. The most significant of the artifacts was a pendant with an early Maya status symbol—a vulture’s head, in jade, lying exactly where the deceased’s chest would have been. He must have been wearing it when he was buried. Schieber and Orrego named him the Vulture Lord (K’utz Chman in the modern Mayan language), and although his bones had long since rotted away, clusters of precious stones showed exactly where he had worn two bracelets, two anklets, and a jade-encrusted loincloth. “The artifacts are wonderful, and they’re clearly not the sort of things that people would have used in daily life. This was a royal tomb,” says Schieber. And perhaps the earliest Maya royal tomb yet discovered, she adds.

Since excavation began there in 1976, Takalik Abaj, “Place of the Standing Stones,” has attracted archaeologists with its carefully laid out early Maya urban environment—there are at least 83 structures and more than 300 sculpted stone monuments. Although few tombs have been discovered thus far, other structures suggest a history of elite pleasures and rituals. One of Mesoamerica’s largest ball courts, measuring 75 by 16 feet, stretches across one of the site’s few flat areas. According to Schieber, one platform may have been an observatory. On its surface, three parallel lines of stone monuments line up with the Big Dipper when it rises just east of true north. Nestled as it was in a mountain pass, the city had extensive trade networks that stretched as far afield as Mexico’s Veracruz state, El Salvador, and the Petén lowlands. Archaeologists believe Takalik Abaj was a cosmopolitan city and a crossroads of peoples and styles. In its stonework and artifacts, Schieber and Orrego see an unusual mix that may hold answers to one of archaeology’s most vexing questions—how and when did the Maya civilization that would dominate the region for almost 1,500 years replace the more ancient Olmec culture?

Known primarily from their cities on the Gulf of Mexico coast, the Olmec initiated many of the achievements usually associated with the Maya, including written language, ball courts, and perhaps urban planning. But how and why they eventually ceded influence to the Maya remains unclear. Schieber believes Takalik Abaj, and the tomb of the Vulture Lord, offer new insights into how that change might have happened. “This period, around 500 B.C., was a period of transition,” says Schieber. “In the stonework at the site’s ceremonial platforms you can see how sculptors were gradually changing their minds and treating the stone in a different way, moving away from the Olmec style.” It’s notable, too, explains Schieber, that all but two of Takalik Abaj’s 354 stone monuments were locally quarried, and that the ceramics were fashioned of local materials. This suggests that the cultural changes in evidence were not the result of the arrival of an alien population such as the Maya bringing its own wares, but of local artisans changing the way they made objects as outside cultural influences seeped in.

Wolf Rites of Winter

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Around 4,000 years ago, on the steppes north of the Black Sea, a nomadic people began settling down in small communities. Known today as the Timber Grave Culture, these people left behind more than 1,000 sites. One of them is called Krasnosamarskoe, and Hartwick College archaeologist David Anthony had big expectations for it when he started digging there in the late 1990s. Anthony hoped that by excavating the site he might learn why people in this region first began to establish permanent households. But he and his team have since discovered that Krasnosamarskoe has a much different story to tell. They found that the site held the remains of dozens of butchered dogs and wolves—vastly more than at any comparable site.

Nerissa Russell, the project’s archaeozoologist, says, “I remember saying early on in the dig that we were finding a lot of dog bones. But I had no idea how important they would turn out to be.” When the team got to work analyzing all the animal bones in the lab, they identified the remains of about 51 dogs and seven wolves, as well as six canines that could not be classified as either. At other Timber Grave sites, dog and wolf bones never make up more than 3 percent of the total animal bones found. At Krasnosamarskoe, they made up more than 30 percent. “I don’t know of any other site in the world with such a high percentage of dog bones,” says Russell. She and her team found that most of the dogs were unusually long-lived, up to 12 years old in some cases, which meant they were probably not raised for food. “Were they treasured pets, hunting dogs, or pariahs? We don’t know,” she says. “But they are so old that these were dogs that had been around for a while and had some kind of relationship to these people.”

To add to the mystery, the bones were cut in unusual, systematic ways that did not resemble ordinary butchering practices. Snouts were divided into three pieces and the remainder of the skulls were broken down into geometrically shaped fragments only an inch long. No one would have made these cuts to simply get meat off the bones.

To add to the mystery, the bones were cut in unusual, systematic ways that did not resemble ordinary butchering practices. Snouts were divided into three pieces and the remainder of the skulls were broken down into geometrically shaped fragments only an inch long. No one would have made these cuts to simply get meat off the bones.

Anthony and his wife, archaeologist Dorcas Brown, knew it was a unique discovery. Brown, in particular, suspected the canines were probably sacrificed there as part of a ritual and decided to examine the research literature broadly on the subject of rituals involving dogs. What she discovered was that there was indeed a body of work on just such ancient practices. In an unusual move for prehistoric archaeologists, they decided to consult historical linguistics and ancient literary traditions to better understand the archaeological record.

|

Online Audio Exclusive:

|

Telling Tales in Proto-Indo-European

|

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

No Changeups on the Savannah

Off the Grid

The Last Flying Pencil

Small Skirmish in the War for Freedom

Sifting Through Molehills

City of Red Stone

Animal Offerings of the Aztecs

High-Definition Obsidian

Tomb of the Wari Queens

Golden Sacrifices

Spain's Lost Jewish History

Samson and the Gate of Gaza

French Wine, Italian Vine

Neanderthal Brain Strain

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

According to Schieber and Orrego, the Vulture Lord’s tomb is a bridge between the two styles, with the Olmec becoming obsolete in his time. “He was a very rich ruler who still had Olmec traditions,” she says. “But he was already showing Maya stylistic influences in the things he took to the grave.” For example, while the vulture and the ceramic women look Maya—that tattoo is an exact match to a mural pattern at the early Maya site of San Bartolo, says Schieber—the jade ornaments on the deceased’s body closely resemble those on a ruler depicted in stone at the Olmec city of La Venta. A pair of charming jade mosaic faces from a separate group of artifacts suggest early Maya iconography. Although excavated by Schieber and Orrego close to the Vulture Lord’s tomb, they date from about five centuries after his lifetime and may be evidence that the Maya transition was complete by then, Schieber explains.

According to Schieber and Orrego, the Vulture Lord’s tomb is a bridge between the two styles, with the Olmec becoming obsolete in his time. “He was a very rich ruler who still had Olmec traditions,” she says. “But he was already showing Maya stylistic influences in the things he took to the grave.” For example, while the vulture and the ceramic women look Maya—that tattoo is an exact match to a mural pattern at the early Maya site of San Bartolo, says Schieber—the jade ornaments on the deceased’s body closely resemble those on a ruler depicted in stone at the Olmec city of La Venta. A pair of charming jade mosaic faces from a separate group of artifacts suggest early Maya iconography. Although excavated by Schieber and Orrego close to the Vulture Lord’s tomb, they date from about five centuries after his lifetime and may be evidence that the Maya transition was complete by then, Schieber explains.

They knew that the people who lived at Krasnosamarskoe almost certainly spoke an Indo-European language. This huge language family today consists of most of the European languages including English, and many spoken in Asia, such as Hindi. All these languages are “daughters” of one language, which was probably spoken on the Eurasian steppes between

They knew that the people who lived at Krasnosamarskoe almost certainly spoke an Indo-European language. This huge language family today consists of most of the European languages including English, and many spoken in Asia, such as Hindi. All these languages are “daughters” of one language, which was probably spoken on the Eurasian steppes between