Features

Vengeance on the Vikings

By NADIA DURRANI

Tuesday, October 01, 2013

On November 13, A.D. 1002, Æthelred Unræd, ruler of the English kingdom of Wessex, “ordered slain all the Danish men who were in England,” according to a royal charter. This drastic step was not taken on a whim, but was the product of 200 years of Anglo-Saxon frustration and fear. Vikings, who had long plagued the Isles with raids and wars, had taken over the north and begun settling there. Concerns were growing that they had designs on Æthelred’s southern realm as well.

Æthelred’s order led to what is known as the St. Brice’s Day Massacre, named for the saint’s feast day on which it fell. The event has long been cloaked in mystery and misinformation. Archaeology, so far, has had little to offer in the matter of what actually happened and how many people died that day, but two mass burials recently unearthed are beginning to expose this turbulent period around the end of the first millennium. Could they be the first archaeological evidence of the massacre? Or might they offer a glimpse into some other aspect of the conflict between Anglo-Saxons and Vikings? Archaeologists are examining a trail of clues, including historical sources, wound patterns, and isotopic analysis of teeth, to put what was no doubt a violent series of deaths into perspective.

The Vikings of popular imagination were raiders and pillagers in longboats and (mythical) horned helmets, but the term “Viking” also refers to the farming, trading, crafting, exploring Scandinavian culture from which these raiders came. The Vikings that attacked and settled England and France were, for the most part, from or identified with Denmark. (The Norwegians went north and west, and the Swedes east, though there was a lot of movement of people among the Viking territories.) Viking raids in England began in the late eighth century A.D. and led to the fall of England’s northern kingdoms. Many of the Danish settlers were warriors granted land as a reward for success in battle. The only Anglo-Saxon holdout was Wessex, a powerful and wealthy kingdom that controlled most of the south of the island. An 878 treaty established the boundaries of Wessex and the Danish-controlled area, known as the Danelaw.

There is much discussion among historians about the nature of the relationship between the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes. Many of the new settlers had once been warriors, but they eventually brought along their families. The Danes farmed, traded, and even intermarried with the Anglo-Saxon population, and their cultural influence can be seen in language, place names, and surnames that persist in England today. Some historians argue that there weren’t all that many Danish settlers and that they assimilated many local traditions and beliefs. But there was likely some tension and resentment between the Danish settlers and the Anglo-Saxons (who, ironically, were also descended from continental invaders).

|

Sidebar:

|

Burial Pit, ca. 960-1020, St. John's College, Oxford

|

Ancient Tattoos

By JARRETT A. LOBELL and ERIC A. POWELL

Wednesday, October 09, 2013

The practice of adorning the body with images and symbols has become nearly ubiquitous in our time, and the reasons for getting a tattoo are enormously varied and highly personal. It was no less so in antiquity as can be seen in this survey of body art that spans thousands of years and an array of cultures—each a unique demonstration of the ways in which peoples across the globe chose to express themselves.

The practice of adorning the body with images and symbols has become nearly ubiquitous in our time, and the reasons for getting a tattoo are enormously varied and highly personal. It was no less so in antiquity as can be seen in this survey of body art that spans thousands of years and an array of cultures—each a unique demonstration of the ways in which peoples across the globe chose to express themselves.

Life on the Inside

By MARGARET SHAKESPEARE

Sunday, November 10, 2013

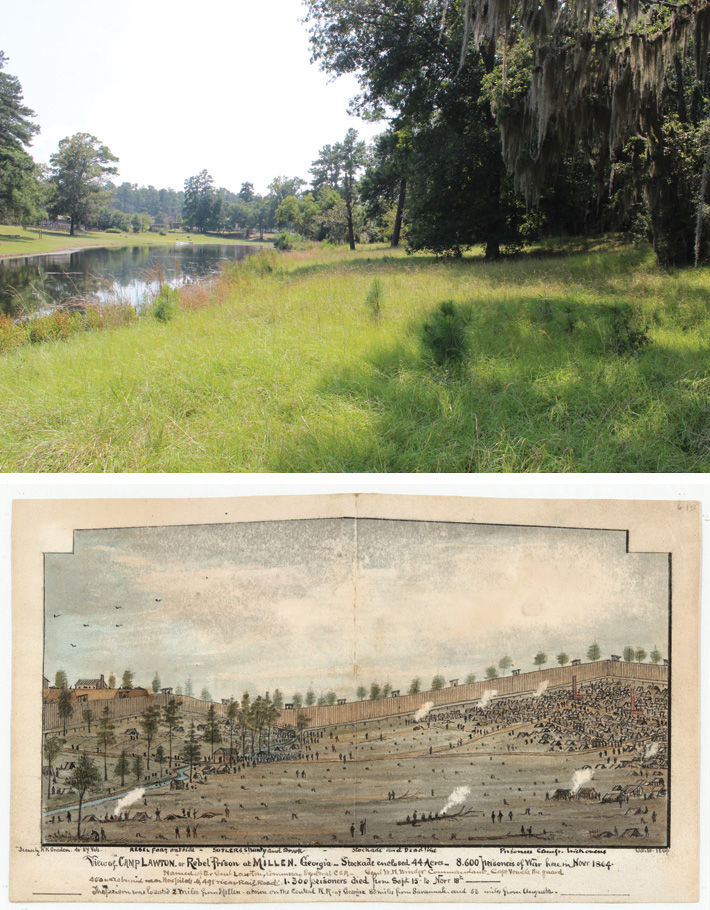

Camp Lawton had been on the mind of John Derden, a professor emeritus of history at East Georgia College, for decades, ever since he visited Magnolia Springs State Park in 1973. The Georgia Department of Natural Resources had turned the springs, which produce seven million gallons of crystal-clear water a day, into a state park in 1939. Some 200 miles southeast of Atlanta, Magnolia Springs is also the location of Camp Lawton, a surprisingly undisturbed Civil War site, where Confederate forces, for a brief time, imprisoned Union enlisted men.

“When I made that first visit, I saw a tablet in the park about the camp,” Derden recalls. He discovered that some rudimentary archaeological surveys—a few shovel tests over the years—had essentially turned up no remains from the nineteenth century. Only some of the surrounding earthworks, where manned munitions had been mounted and aimed menacingly toward the prison population, still stood. Derden, like pretty much everyone else, assumed no significant remains were left to help advance any chronicle of the camp and its inhabitants.

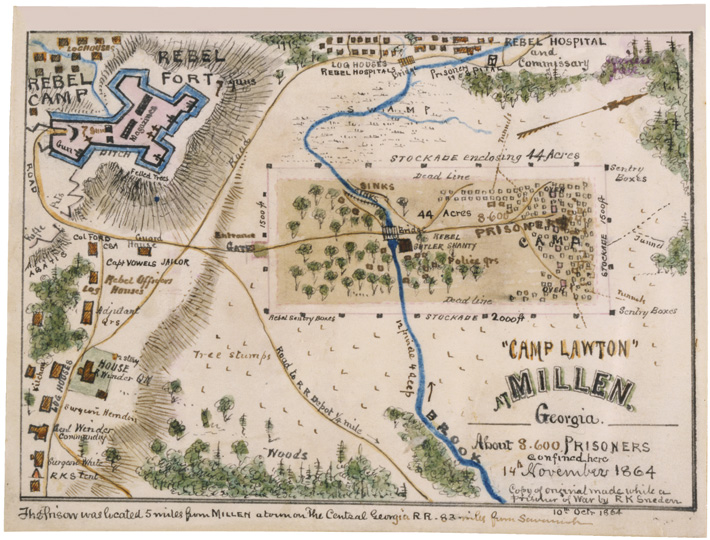

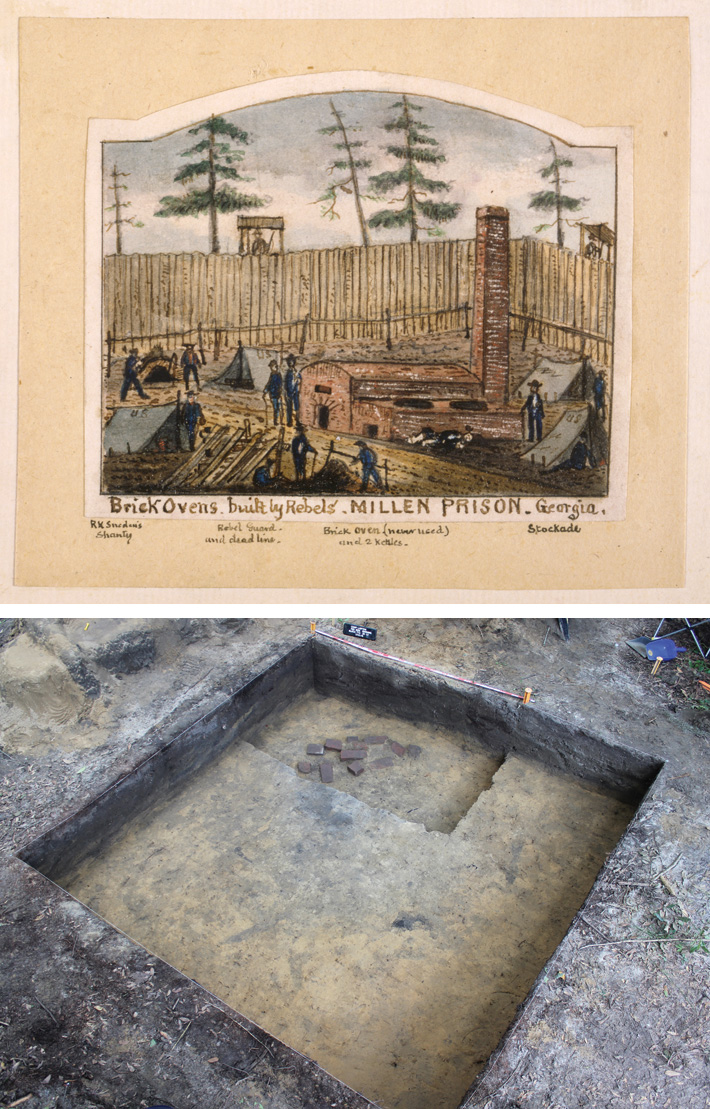

Nonetheless convinced of a worthy narrative, Derden plugged away at putting one together, relying on other sources, such as diaries and letters from the time, including the drawings and accounts of Private Robert Knox Sneden, a Union prisoner in the camp. Derden’s research revealed that Camp Lawton, a functioning prison for only six weeks, would end up being burned to the ground at the hands of Union General William Tecumseh Sherman in December 1864 as the Civil War drew toward its end. The prison had held upwards of 10,000 individuals on more than 42 acres fortified by an imposing pine-log stockade. Of those 10,000 Union prisoners, more than 700 died during their brief time at Camp Lawton. The survivors were evacuated in a hasty nighttime maneuver just one month before Sherman swept through the region. After these events, the camp was pretty much forgotten.

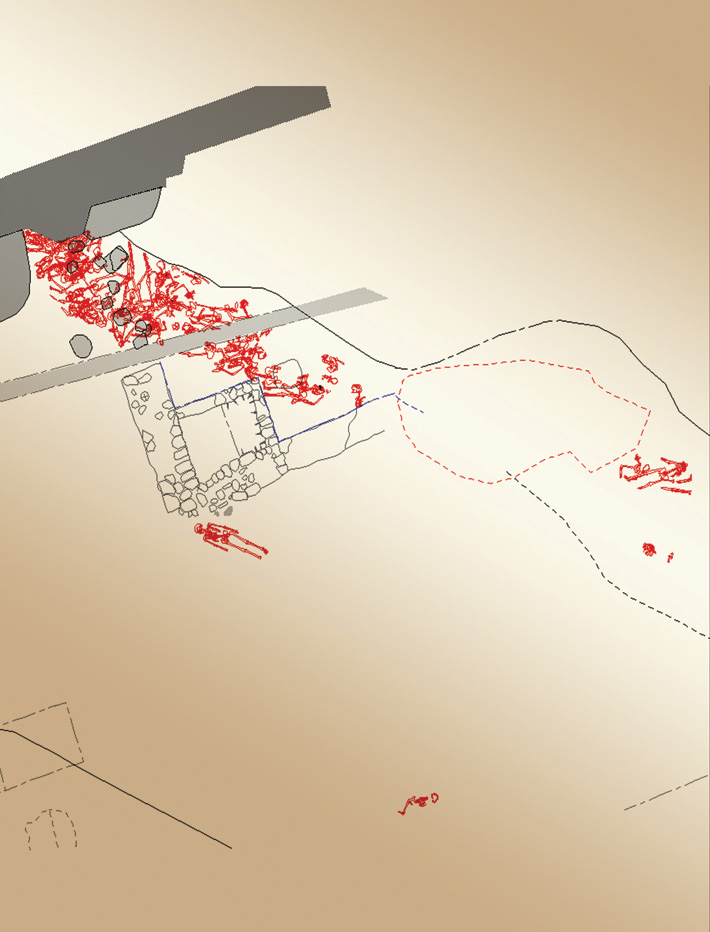

Derden’s scholarship resulted in a completed manuscript, The World’s Largest Prison: The Story of Camp Lawton. As it was about sent to the publisher in 2010, in an interesting twist, Derden and other historians, archaeologists, Civil War buffs, and locals were stunned to learn that Kevin Chapman, a graduate student at nearby Georgia Southern University, just 40 minutes down the road from the site, not only had discovered intriguing Civil War–era artifacts, but also had successfully located pieces of the prison’s burned stockade wall. As news hit The New York Times, CNN, and other national outlets, Derden had just enough time to tuck a final chapter into his book. Excavation of the site then cranked into full gear, led by Lance Greene, an assistant professor of anthropology at Georgia Southern, with Derden serving as an ad hoc adviser and expert. Archaeological evidence can now be brought to bear on nuances of daily subsistence in a community that existed for a mere month and a half in the fall of 1864. “This might be the last chance to look at a debate that still rages,” says Greene. “Who was to blame for dying prisoners? Were Confederates trying to starve them out?” Looking for answers to these questions is just a piece of the effort. The archaeologists are also searching for clues as to whether life was better or worse, depending on which side of the stockade wall a person found himself.

|

Sidebar:

|

Online Exclusive:

|

Camp Lawton's Stockade and Forgotten Population

|

A Civil War POW Camp in Watercolor

|

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

An Imperial Underworld

Off the Grid

Splendid Surprise

Neanderthal Tool Time

Dutchman Out of His Depth

Catching a Ride from Ireland

The Snake King's New Vassal

Spying the Past from the Sky

Byzantine Riches

The Neolithic Palate

Secrets of Life in the Soil

Who Was First to the Faroes?

Drones Enter the Archaeologist's Toolkit

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Isotopic analysis of these remains by Jane Evans and Carolyn Chenery at NERC Isotope Geosciences Laboratory, part of the British Geological Survey, shows that the men originated from a variety of places across the Viking territory. The isotopes in their teeth confirmed that, like the remains found in Oxford, the men grew up in countries colder than Britain, with one individual thought to be from north of the Arctic Circle, and that the men had eaten a diet high in protein, another marker of Scandinavian origin. Radiocarbon analysis returned dates of between 980 and 1030 for their deaths—broadly contemporary with the St. Brice’s Day Massacre. Here was a group that may or may not have been victims of Æthelred’s order. Regardless, they were clearly not settlers, but rather Viking mercenaries or warriors of some sort.

Isotopic analysis of these remains by Jane Evans and Carolyn Chenery at NERC Isotope Geosciences Laboratory, part of the British Geological Survey, shows that the men originated from a variety of places across the Viking territory. The isotopes in their teeth confirmed that, like the remains found in Oxford, the men grew up in countries colder than Britain, with one individual thought to be from north of the Arctic Circle, and that the men had eaten a diet high in protein, another marker of Scandinavian origin. Radiocarbon analysis returned dates of between 980 and 1030 for their deaths—broadly contemporary with the St. Brice’s Day Massacre. Here was a group that may or may not have been victims of Æthelred’s order. Regardless, they were clearly not settlers, but rather Viking mercenaries or warriors of some sort.

Greene has also found spoons, about four inches long, with the handles bent at almost a 90-degree angle, no doubt used as “a tool of some kind.” The team has also located parts of scissors, pockets knives, lead bullets carved into nipples to keep powder dry, bullets cut for chess pieces, heel taps, key rings, knapsack hooks, and many service buttons (usually marked by the manufacturer and, hence, easy to trace). Electrolysis labs, some set up in the field, are removing rust from the metal artifacts, and a local veterinarian has volunteered to X-ray some of the more fragile and excessively rusted items.

Greene has also found spoons, about four inches long, with the handles bent at almost a 90-degree angle, no doubt used as “a tool of some kind.” The team has also located parts of scissors, pockets knives, lead bullets carved into nipples to keep powder dry, bullets cut for chess pieces, heel taps, key rings, knapsack hooks, and many service buttons (usually marked by the manufacturer and, hence, easy to trace). Electrolysis labs, some set up in the field, are removing rust from the metal artifacts, and a local veterinarian has volunteered to X-ray some of the more fragile and excessively rusted items.