Top 10

North America’s Oldest Petroglyphs

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

Paleoindians are often thought of as pioneering explorers or expert mammoth hunters. But new dating of geometric rock carvings in Nevada’s Winnemucca Lake basin now suggests they were also accomplished artists.

A team led by University of Colorado paleoclimatologist Larry Benson was able to date the carbonate crust that covers the petroglyphs. Benson concluded that the artwork must have been created more than 10,000 years ago, before the carvings were submerged beneath the lake’s higher waters and covered in carbonate. “We knew they were old,” he says. “We just didn’t know they were that old.” According to Benson, it’s possible that paleoartists made the carvings as early as 15,000 years ago.

Just what those artists meant to depict is unclear. Some of the petroglyphs may represent clouds and lightning, others are diamond- shaped, and there are some patterns that might represent trees. Whatever the inspiration for the carvings, the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, which owns the Winnemucca Lake basin, considers them sacred to this day.

Remapping the Khmer Empire

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

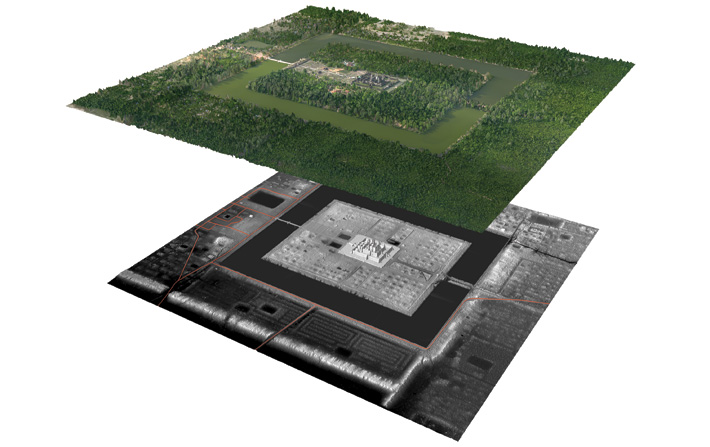

Airborne laser sensing peered beneath vast stretches of centuries-old tree cover to reshape archaeologists’ understanding of the ancient Angkor region, once the epicenter of the Khmer Empire. Previously, scholars believed Khmer cities and temple complexes were enclosed spaces with walls or moats surrounding gridded “downtowns.”

Using lidar, a team led by Damian Evans, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Sydney, showed that these grids extended beyond the fortifications, creating much bigger urban landscapes. For instance, the mapping project turned up evidence of urbanization on both sides of Angkor Wat’s famed moat. Meanwhile, the twelfth-century A.D. Khmer capital Angkor Thom has now quadrupled in size. Imaging showed that its city-block structure extended far beyond the three-and-a-half square miles contained within its walls. It actually encompass more than 13 square miles of formally planned urban space, including within it Angkor Wat, which predated Angkor Thom by 100 years and sits a mile south of the city’s center.

The findings lend support to the theory that Angkor fell because it grew beyond its means. “What you have is an urban structure that is analogous to the giant, low-density megacities that have developed in the twentieth century with the advent of the car,” Evans explains, “a dense urban core surrounded by a vast lower-density periphery, or ‘sprawl.’”

World’s Oldest Port

By ROSSELLA LORENZI

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

While excavating an underground storage system cut into bedrock at Wadi el-Jarf, nearly 110 miles south of Suez and close to the Red Sea, archaeologists discovered fragments of boats, ropes, and pottery. The artifacts date to the reign of the 4th Dynasty King Khufu, or Cheops, builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza, who ruled from 2551 to 2528 B.C.

Beginning on the shore and continuing underwater, an assembly of large blocks and limestone slabs inscribed with Cheops’ name form the remains of an L-shaped jetty. Limestone anchors from numerous large ships testify to voyages launched to export copper and stones from the Sinai Peninsula to the Nile Valley. “Ancient inland harbors are known on riversides, but the jetty of Wadi el-Jarf predates by more than 1,000 years any other known structure of this kind,” says expedition leader Pierre Tallet, a University of Paris-Sorbonne Egyptologist, about the 4,500-year-old harbor.

Beginning on the shore and continuing underwater, an assembly of large blocks and limestone slabs inscribed with Cheops’ name form the remains of an L-shaped jetty. Limestone anchors from numerous large ships testify to voyages launched to export copper and stones from the Sinai Peninsula to the Nile Valley. “Ancient inland harbors are known on riversides, but the jetty of Wadi el-Jarf predates by more than 1,000 years any other known structure of this kind,” says expedition leader Pierre Tallet, a University of Paris-Sorbonne Egyptologist, about the 4,500-year-old harbor.

Tallet and colleagues also found 10 very well-preserved papyri among hundreds of fragments. The documents, which are proving difficult to reassemble, are the oldest papyri ever found in Egypt. One fragment is a diary written by Merrer, an Old Kingdom official involved in the building of the Great Pyramid. Though actual details of the pyramid’s construction are scarce, Tallet says, "the journal provides a precise account for every working day."

Colonial Cannibalism

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

Six different accounts from Jamestown, the first permanent English colony in the New World, describe episodes of cannibalism among colonists. Former Jamestown president George Percy wrote in 1625 that, during the brutal 1609–1610 winter that caused mass starvation among 300 settlers, “notheinge was Spared to mainteyne Lyfe … as to digge upp deade corpes outt of graves and to eate them.”

Six different accounts from Jamestown, the first permanent English colony in the New World, describe episodes of cannibalism among colonists. Former Jamestown president George Percy wrote in 1625 that, during the brutal 1609–1610 winter that caused mass starvation among 300 settlers, “notheinge was Spared to mainteyne Lyfe … as to digge upp deade corpes outt of graves and to eate them.”

William Kelso, an archaeologist with Preservation Virginia who has excavated Jamestown since 1994, doubted Percy’s horrific descriptions—until this spring, when his team found the butchered skull of a 14-year-old girl buried in a trash pit along with the remains of horses and dogs, other sources of food for the desperate colonists. Jane, as the girl is now known, was originally thought to have been an upper-class settler, but recent analysis found her skeleton has low lead levels. The rich at Jamestown ate from pewter dishes, essentially giving themselves lead poisoning.

Jane’s remains are the first physical evidence of cannibalism at any American colony. “There’s no doubt cannibalism happened,” says Kelso. “It says how close to failure this colony came.”

Critter Diggers

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

Fieldwork can be uncomfortable for long-legged humans, but burrowing animals are built for digging. Furry creatures have provided invaluable assists at two different European sites. In northern Germany, a badger discovered nine remarkable 900-year-old burials, including that of a richly outfitted warrior. “There was no knowledge of these graves and no reason to investigate without the badger’s assistance,” says archaeologist Felix Biermann, who continues to dig the site. In Cumbria, England, burrowing moles have pushed up ancient objects at second-century Whitley Castle, uncovering invaluable evidence of Roman life at the fort. There have only been two previous digs, and Whitley Castle is now a protected site that human archaeologists can never explore. And not to be outdone by their terrestrial counterparts, specially trained mine-hunting dolphins discovered a nineteenth-century Howell torpedo off the coast of San Diego. Only 50 Howells were made, and only two had previously been found.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement