Features

Messengers to the Gods

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

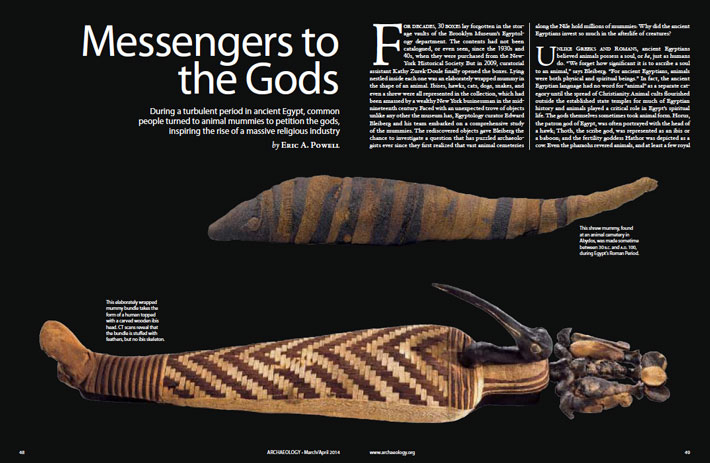

For decades, 30 boxes lay forgotten in the storage vaults of the Brooklyn Museum’s Egyptology department. The contents had not been catalogued, or even seen, since the 1930s and 40s, when they were purchased from the New-York Historical Society. But in 2009, curatorial assistant Kathy Zurek-Doule finally opened the boxes. Lying nestled inside each one was an elaborately wrapped mummy in the shape of an animal. Ibises, hawks, cats, dogs, snakes, and even a shrew were all represented in the collection, which had been amassed by a wealthy New York businessman in the mid-nineteenth century. Faced with an unexpected trove of objects unlike any other the museum has, Egyptology curator Edward Bleiberg and his team embarked on a comprehensive study of the mummies. The rediscovered objects gave Bleiberg the chance to investigate a question that has puzzled archaeologists ever since they first realized that vast animal cemeteries along the Nile hold millions of mummies: Why did the ancient Egyptians invest so much in the afterlife of creatures?

Unlike Greeks and Romans, ancient Egyptians believed animals possess a soul, or ba, just as humans do. “We forget how significant it is to ascribe a soul to an animal,” says Bleiberg. “For ancient Egyptians, animals were both physical and spiritual beings.” In fact, the ancient Egyptian language had no word for “animal” as a separate category until the spread of Christianity. Animal cults flourished outside the established state temples for much of Egyptian history and animals played a critical role in Egypt’s spiritual life. The gods themselves sometimes took animal form. Horus, the patron god of Egypt, was often portrayed with the head of a hawk; Thoth, the scribe god, was represented as an ibis or a baboon; and the fertility goddess Hathor was depicted as a cow. Even the pharaohs revered animals, and at least a few royal pets were mummified. In 1400 B.C., the pharaoh Amenhotep II went to the afterlife accompanied by his hunting dog, and a decade later his heir Thutmose IV was buried with a royal cat.

However, large numbers of mummies in dedicated animal necropolises did not appear until after the fall of the New Kingdom, around 1075 B.C. During the subsequent chaotic 400-year span known as the Third Intermediate Period, the central Egyptian state collapsed and a series of local dynasties and foreign kings rose and fell in rapid succession. This time is often depicted as calamitous in official accounts, but Bleiberg notes that during the First Intermediate Period, a similarly chaotic era without central authority that lasted from 2181 to 2055 B.C., life for the average Egyptian went on as normal. In fact, University of Cambridge Egyptologist Barry Kemp has shown that villagers were relatively prosperous during this time, perhaps because they paid taxes only to local authorities, and not to the central state. If life in the Third Intermediate Period was similar, then the average Egyptian may have had more disposable income. With no pharaoh to mediate Egypt’s relationship to the gods, and with foreigners undermining religious traditions, there was also a turn to personal piety among the general public. “Without the pharaoh, people needed to approach the gods on their own,” says Bleiberg.

|

Online Exclusive:

|

Animal Mummy Coffins of Ancient Egypt

|

All Hands on Deck

By LAUREN HILGERS

Wednesday, March 19, 2014

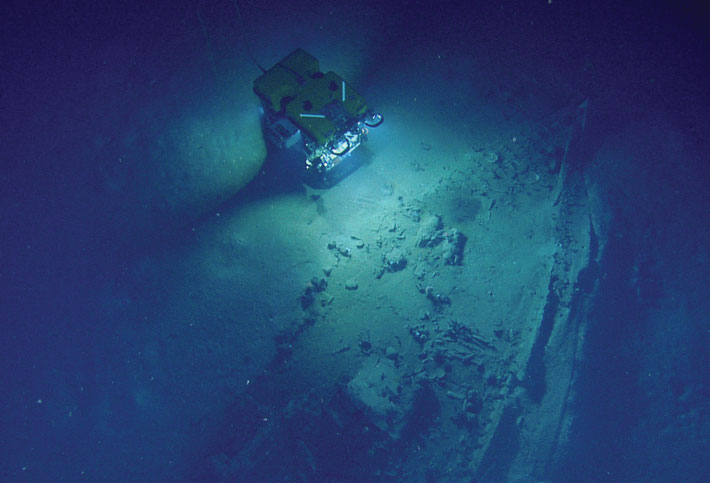

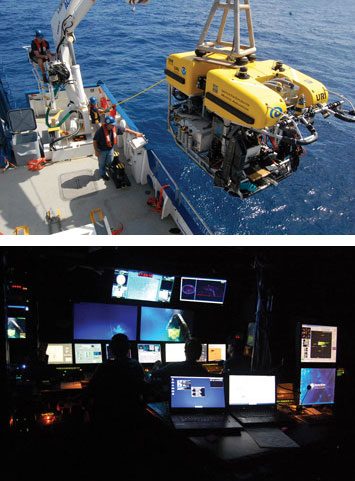

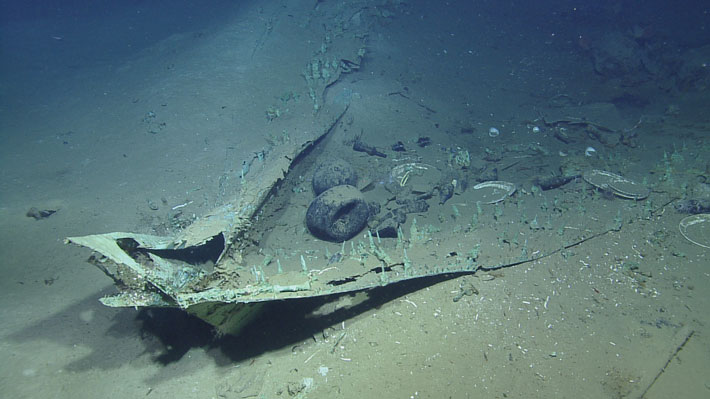

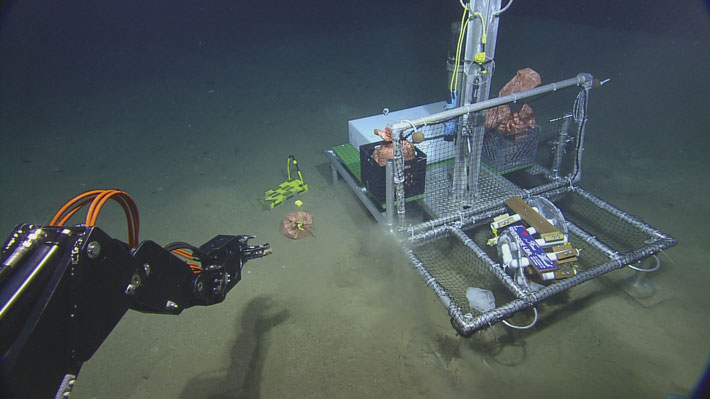

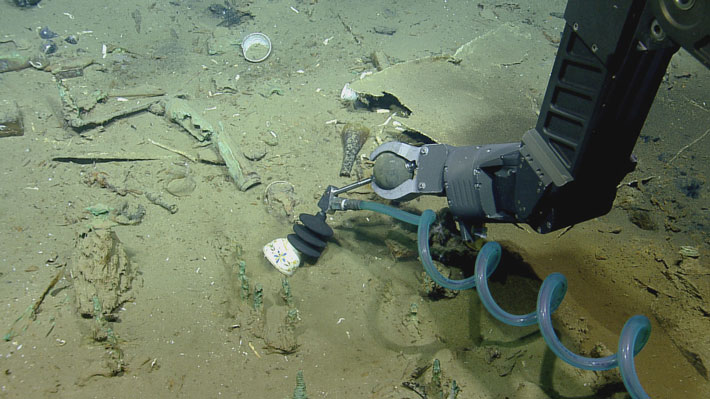

At the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, far enough from both shore and surface that the water no longer carries the silt of the Mississippi, the wreck of a ship rests at a slight angle. The boat’s structure has collapsed and artifacts litter the sandy seafloor—ceramics, demijohns, old medicine bottles, and more. Copper nails and bronze spikes stand in lines where the planks they once held together have partially rotted away. Crouching in the shadow of a toppled, heavily concreted old stove, a long-legged black crab eyes an odd interloper with suspicion. At 4,300 feet below the surface, no human—archaeologist or otherwise—should be bothering it. But, with the help of a remotely operated submersible named Hercules—Herc for short—the crab is enduring a moment of online celebrity. “Folks at shoreside would like to get a measurement on that crab,” a voice crackles over the live video feed. “And let’s take a look at those cannons.”

From where Herc hovers, just above the ocean floor, cables stretch up through thousands of feet of murky water to a state-of-the-art research vessel called Nautilus. There, in a room illuminated only by video screens, James Delgado, underwater archaeologist and director of Maritime Heritage at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and Brendan Phillips, one of Herc’s pilots, guide the exploration of the eighteenth- or nineteenth-century wreck they call Monterrey A. From Nautilus, the video feed from Herc is sent by satellite to a building on the campus of the University of Rhode Island. It also goes to various other “command centers,” where groups of scientists gather to communicate directly with an archaeologist on watch duty and to help guide the exploration. The feed is also being streamed live over the Internet, so thousands more people across the world can write in with questions or just have a moment with this big crab and the shipwreck it lives on.

“What’s giving us a sense of the nineteenth century are the anchors, cannons, some of the bottles, and the navigational instruments,” says Delgado on the video feed. “And if the ship had been abandoned, the captain would have grabbed the instruments to navigate the small boat away. This suggests these guys did not make it.”

The study of the Monterrey A has been a landmark project, bringing together archaeologists from around the country in a collaboration facilitated by telepresence—a technology similar to videoconferencing. Except, in this case, the technology is connecting a robot thousands of feet underwater, a ship bobbing 170 miles out to sea, and rooms full of experts on land. The excavation, conducted over seven days in July 2013, was inclusive and public, as anyone with a computer could ride shotgun with Herc and observe the successes and challenges of deepwater archaeology. And, through the wreck, online viewers could explore a time when the Gulf of Mexico was the epicenter of shifting empires—plied with merchant, naval, and privateer ships on missions of commerce, war, and thievery.

The study of the Monterrey A has been a landmark project, bringing together archaeologists from around the country in a collaboration facilitated by telepresence—a technology similar to videoconferencing. Except, in this case, the technology is connecting a robot thousands of feet underwater, a ship bobbing 170 miles out to sea, and rooms full of experts on land. The excavation, conducted over seven days in July 2013, was inclusive and public, as anyone with a computer could ride shotgun with Herc and observe the successes and challenges of deepwater archaeology. And, through the wreck, online viewers could explore a time when the Gulf of Mexico was the epicenter of shifting empires—plied with merchant, naval, and privateer ships on missions of commerce, war, and thievery.

|

Sidebar:

|

Update:

|

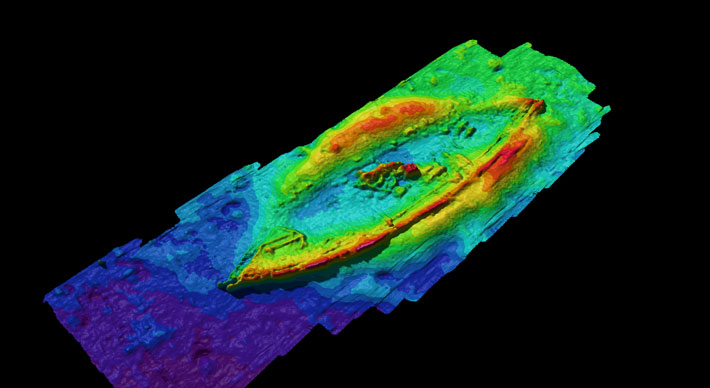

Anatomy of a Deep Wreck

|

Update from 716 Fathoms

|

Saving the Villa of the Mysteries

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, February 10, 2014

The moment the Villa of the Mysteries was discovered in spring 1909, it was at risk. Once protected by a layer of at least 30 feet of the volcanic ash and soil that had fallen on Pompeii in A.D. 79, the villa’s stunning decoration was immediately exposed to potential damage from the elements and earthquakes, one of which occurred a bit more than a month after excavations began. As each wheelbarrow of debris was removed, revealing columns, artifacts, mosaics, and frescoes, the threat increased. It soon became clear that the house and its vibrant paintings were extraordinarily vulnerable, not only to sun, rain, and wind, but also to theft. Just three weeks after the discovery of one of the most stunning finds in the famed ancient city, excavations were halted and the focus shifted to protection and conservation. It would take archaeologists two more decades to completely excavate the property.

For more than a century, there have been many efforts, some successful, some less so, to conserve the villa’s walls, floors, and frescoes. Now, several teams of archaeologists, architects, chemists, and physicists have embarked on a yearlong project, using both time-tested methods and innovative technologies, to remedy the damage done by earlier conservators and by time, and to restore the villa and its remarkable interior once again.

Built just outside one of Pompeii’s main gates in the first half of the second century B.C., the Villa of the Mysteries covered about 40,000 square feet and had at least 60 rooms. In A.D. 79, the house was already more than two hundred years old and had likely had several different owners, been redecorated, and been heavily repaired, particularly after a large earthquake struck Pompeii in A.D. 62, damaging many buildings and necessitating repairs all over the city. At various times the villa functioned, as many ancient Roman estates did, as both luxury home and working farm. There were areas for pressing grapes into wine, several large kitchens and baths, gardens, shrines, marble statues, and all the spaces necessary for a wealthy patron to welcome guests for both business and pleasure. Many rooms were covered in frescoes, including a bedroom with simple black walls, an atrium decorated with panels painted to resemble stone, several rooms that contain fantastical architecture and landscapes, and scenes of sacrifices, gods, and satyrs.

Built just outside one of Pompeii’s main gates in the first half of the second century B.C., the Villa of the Mysteries covered about 40,000 square feet and had at least 60 rooms. In A.D. 79, the house was already more than two hundred years old and had likely had several different owners, been redecorated, and been heavily repaired, particularly after a large earthquake struck Pompeii in A.D. 62, damaging many buildings and necessitating repairs all over the city. At various times the villa functioned, as many ancient Roman estates did, as both luxury home and working farm. There were areas for pressing grapes into wine, several large kitchens and baths, gardens, shrines, marble statues, and all the spaces necessary for a wealthy patron to welcome guests for both business and pleasure. Many rooms were covered in frescoes, including a bedroom with simple black walls, an atrium decorated with panels painted to resemble stone, several rooms that contain fantastical architecture and landscapes, and scenes of sacrifices, gods, and satyrs.

The most spectacular frescoes, painted in the mid-first century B.C., were found less than a week after excavations began, in an approximately 15-by-15-foot space that was likely used as a dining room. There, against a vivid red background, more than two dozen life-size figures engage in what has been variously interpreted as a play or pantomime, a bride’s preparations for her wedding, or, most often, an initiation ritual into the mystery cult of Dionysus. (In contrast to recognized public religion and worship, in the Greco-Roman world the mystery cults required the worshipper to be initiated.)

For more than two decades the house was known as the “Villa Item” after Aurelio Item, owner of Pompeii’s Hotel Suisse, and the private excavator who first discovered the villa. But in 1931, Amadeo Maiuri, the director of excavations at Pompeii, changed the name to the “Villa of the Mysteries” upon publication of his excavation report to focus attention on the red room’s decoration, the property’s most extraordinary feature.

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Saving the Villa of the Mysteries

All Hands on Deck

Messengers to the Gods

Letter From Borneo

From the Trenches

Our Tangled Ancestry

Off the Grid

Viking Finery

Scuttled but Not Forgotten

Game of Stones

How to Pray to a Storm God

Triangulating Buddha's Birth

Mesopotamian Accounts Receivable

Barbarian Body Modification

Did Neanderthals Bury Their Dead?

Florida History Springs Forth

Turtle Power

Battle of the Proxies

World Roundup

Aztec god of the dead, gold in Lake Titicaca, Anglo-Saxon gaming piece, and building the Forbidden City

Artifact

The importance of music in Peru

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

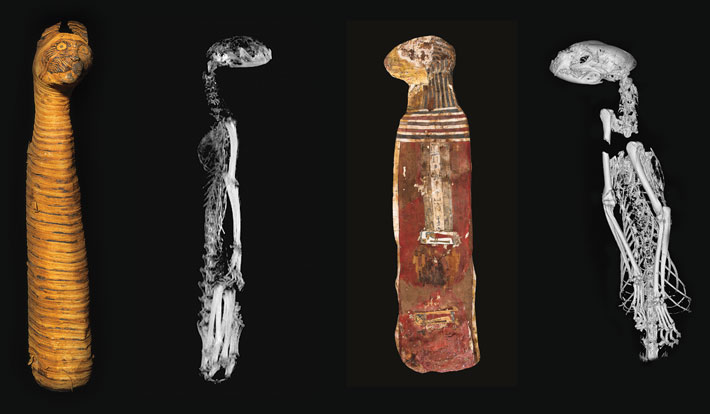

X-rays and CT scans of the mummies in the rediscovered Brooklyn Museum collection reveal just how diverse animal mummies could be. While many show entire skeletons inside the mummy bundles, others reveal only partial remains. Some even show multiple animals mummified together in one bundle. A particularly poignant CT scan of a cat bundle shows that the feline was mummified with its forepaws crossed in the same position as human mummies’ arms were crossed, a reminder that the ancient Egyptians drew little distinction between people and animals. To determine if different wrapping styles could be dated to particular periods, Bleiberg took radiocarbon samples of some of the mummies’ linens, but the dates turned out to be inconsistent. It’s possible that the linen used in the wrappings was often recycled, which makes dating unreliable. A piece of linen could begin life as an article of clothing that lasted for decades, then be used as a rag, and then be repurposed as mummy wrapping, perhaps decades, or even centuries, after it was first made. Given the scale of the animal mummy-making business, some temples may have made their own linen, just as they raised their own animals in numbers approaching modern-day industrial farming. “This was an extremely important economic phenomenon,” says Bleiberg. “ There was a lot of money being directed toward animal mummies in first millennium.”

X-rays and CT scans of the mummies in the rediscovered Brooklyn Museum collection reveal just how diverse animal mummies could be. While many show entire skeletons inside the mummy bundles, others reveal only partial remains. Some even show multiple animals mummified together in one bundle. A particularly poignant CT scan of a cat bundle shows that the feline was mummified with its forepaws crossed in the same position as human mummies’ arms were crossed, a reminder that the ancient Egyptians drew little distinction between people and animals. To determine if different wrapping styles could be dated to particular periods, Bleiberg took radiocarbon samples of some of the mummies’ linens, but the dates turned out to be inconsistent. It’s possible that the linen used in the wrappings was often recycled, which makes dating unreliable. A piece of linen could begin life as an article of clothing that lasted for decades, then be used as a rag, and then be repurposed as mummy wrapping, perhaps decades, or even centuries, after it was first made. Given the scale of the animal mummy-making business, some temples may have made their own linen, just as they raised their own animals in numbers approaching modern-day industrial farming. “This was an extremely important economic phenomenon,” says Bleiberg. “ There was a lot of money being directed toward animal mummies in first millennium.”

Not all of these sonar hits are examined further, but BOEM’s tally went into the planning for NOAA’s 2012 summer exploration season on the government research vessel Okeanos. The ship was scheduled to be in the Gulf of Mexico and, based on meetings with scientists in the area, NOAA compiled plans for biological, geological, and archaeological studies, including a look at the sonar anomaly at Monterrey A. “We almost didn’t make it to the wreck site,” says Delgado.

Not all of these sonar hits are examined further, but BOEM’s tally went into the planning for NOAA’s 2012 summer exploration season on the government research vessel Okeanos. The ship was scheduled to be in the Gulf of Mexico and, based on meetings with scientists in the area, NOAA compiled plans for biological, geological, and archaeological studies, including a look at the sonar anomaly at Monterrey A. “We almost didn’t make it to the wreck site,” says Delgado.

Despite the hiccups, Irion thinks the openness and transparency of the project made the excavation more interesting. “The more eyes on this, the more details you catch,” he says. Archaeologists got to see what most engages the public, while enthusiasts got to see how archaeologists begin the process of studying an unknown wreck.

Despite the hiccups, Irion thinks the openness and transparency of the project made the excavation more interesting. “The more eyes on this, the more details you catch,” he says. Archaeologists got to see what most engages the public, while enthusiasts got to see how archaeologists begin the process of studying an unknown wreck.

By 2013 the villa, like most of Pompeii, was in dire need of modern conservation, as was a protective covering that had been constructed in different phases throughout the years. Parts of paintings were crumbling from unstable walls and the mosaics had been severely damaged by millions of visitors’ feet. Repeated applications of wax had caused the pigments to oxidize and darken, and the frescoes to yellow, significantly altering their appearance. “All the surface decorations of the villa, both mosaics and frescoes, had been conserved before, but in an irregular way,” says Stefano Vanacore, director of the restoration laboratory at Pompeii. “But there has never been a large, comprehensive program like we are doing now. We are looking at every single surface to analyze the materials used, both ancient and modern, and to research the causes of the deterioration. Only then can we restore the villa properly.”

By 2013 the villa, like most of Pompeii, was in dire need of modern conservation, as was a protective covering that had been constructed in different phases throughout the years. Parts of paintings were crumbling from unstable walls and the mosaics had been severely damaged by millions of visitors’ feet. Repeated applications of wax had caused the pigments to oxidize and darken, and the frescoes to yellow, significantly altering their appearance. “All the surface decorations of the villa, both mosaics and frescoes, had been conserved before, but in an irregular way,” says Stefano Vanacore, director of the restoration laboratory at Pompeii. “But there has never been a large, comprehensive program like we are doing now. We are looking at every single surface to analyze the materials used, both ancient and modern, and to research the causes of the deterioration. Only then can we restore the villa properly.”

Though these walls are durable, they still must be handled carefully. “We felt that lasers were a good method to clean the frescoes because they allow for the gentle cleaning of hard surfaces, and there is minimal impact on the work of art,” says Vanacore. Although lasers are generally used for cleaning stone, they have been tested on metals and pottery as well to great success. The process by which the lasers clean the frescoes—a few microns at a time—is called photoablation, a sort of vaporization of what can appear as a layer of black crust. “This allows for precise cleaning of very delicate surfaces, and it’s also much less time consuming than using a scalpel or chemicals,” Vanacore adds. Even where the surface is very degraded, lasers can remove minuscule amounts of dirt without affecting the layer underneath, revealing as much of the ancient painting as possible without putting it at risk.

Though these walls are durable, they still must be handled carefully. “We felt that lasers were a good method to clean the frescoes because they allow for the gentle cleaning of hard surfaces, and there is minimal impact on the work of art,” says Vanacore. Although lasers are generally used for cleaning stone, they have been tested on metals and pottery as well to great success. The process by which the lasers clean the frescoes—a few microns at a time—is called photoablation, a sort of vaporization of what can appear as a layer of black crust. “This allows for precise cleaning of very delicate surfaces, and it’s also much less time consuming than using a scalpel or chemicals,” Vanacore adds. Even where the surface is very degraded, lasers can remove minuscule amounts of dirt without affecting the layer underneath, revealing as much of the ancient painting as possible without putting it at risk. As part of the overall examination of the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii’s archaeological superintendency, which oversees all work in the ancient city, also invited a team from the University of Kiel in Germany to investigate the house also using some of the latest technology available to archaeologists and conservators. Since it is no longer accepted practice to detach the paintings from the walls as the first conservators did, the Kiel team had to look to other techniques, such as those they used during a 2012 research project in the House of the Tragic Poet—another of Pompeii’s well decorated properties and home to the beloved “Beware of the Dog” mosaic—to investigate the damage to both the paintings and the underlying walls. “We wanted to employ nondestructive techniques to quantify the properties of the villa’s ancient painting and walls in order to identify the level of decay,” says Luigia Cristiano, a team member and researcher at Kiel’s Institute of Geoscience. Using a combination of these sophisticated methods, the Kiel team has been able to create precise maps that can be used to better direct the restoration of the villa.

As part of the overall examination of the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii’s archaeological superintendency, which oversees all work in the ancient city, also invited a team from the University of Kiel in Germany to investigate the house also using some of the latest technology available to archaeologists and conservators. Since it is no longer accepted practice to detach the paintings from the walls as the first conservators did, the Kiel team had to look to other techniques, such as those they used during a 2012 research project in the House of the Tragic Poet—another of Pompeii’s well decorated properties and home to the beloved “Beware of the Dog” mosaic—to investigate the damage to both the paintings and the underlying walls. “We wanted to employ nondestructive techniques to quantify the properties of the villa’s ancient painting and walls in order to identify the level of decay,” says Luigia Cristiano, a team member and researcher at Kiel’s Institute of Geoscience. Using a combination of these sophisticated methods, the Kiel team has been able to create precise maps that can be used to better direct the restoration of the villa. Other methods can go even deeper below the surface. Using devices that emit and sense returning electromagnetic waves, which scatter differently depending on the materials they pass through and the depth they reach, the Kiel team was able to create images of the internal structure of the walls. The scattering properties of electromagnetic waves depend on the walls’ material composition and level of water saturation. “All the images arrived at using these technologies will help to devise an effective plan for future conservation,” says Cristiano.

Other methods can go even deeper below the surface. Using devices that emit and sense returning electromagnetic waves, which scatter differently depending on the materials they pass through and the depth they reach, the Kiel team was able to create images of the internal structure of the walls. The scattering properties of electromagnetic waves depend on the walls’ material composition and level of water saturation. “All the images arrived at using these technologies will help to devise an effective plan for future conservation,” says Cristiano.

As modern visitors to Pompeii walk along the miles of ancient streets paved with original stones, through the forum where temples and warehouses still stand, past a bakery with its enormous grindstone, and inside the bars, shops, houses, and brothels that still line the carefully planned streets, it’s easy to believe that the city appears almost exactly as it did on the day Mount Vesuvius erupted almost two millennia ago. Nowhere does this seem to be more true, perhaps, than in the Villa of the Mysteries. Ancient mosaics still decorate the villa’s original floors, and stunning frescoes are still visible on the walls they have always covered. The villa stands in high contrast to many of the city’s homes where lavish decoration was lost to looters or removed to private collections and museums across the world beginning soon after the city’s mid-eighteenth-century discovery. But when the decision was made very early on to leave the paintings in place, the challenges of how to protect the villa began immediately—as did the multitude of factors that have affected its original appearance. Thus, what can be seen today in Pompeii is not only the result of having been buried by volcanic debris, but also the work of centuries of private excavators and professional archaeologists—and even the misdeeds of treasure hunters—who have plundered, excavated, rebuilt, and conserved the ancient city and its most remarkable private house.

As modern visitors to Pompeii walk along the miles of ancient streets paved with original stones, through the forum where temples and warehouses still stand, past a bakery with its enormous grindstone, and inside the bars, shops, houses, and brothels that still line the carefully planned streets, it’s easy to believe that the city appears almost exactly as it did on the day Mount Vesuvius erupted almost two millennia ago. Nowhere does this seem to be more true, perhaps, than in the Villa of the Mysteries. Ancient mosaics still decorate the villa’s original floors, and stunning frescoes are still visible on the walls they have always covered. The villa stands in high contrast to many of the city’s homes where lavish decoration was lost to looters or removed to private collections and museums across the world beginning soon after the city’s mid-eighteenth-century discovery. But when the decision was made very early on to leave the paintings in place, the challenges of how to protect the villa began immediately—as did the multitude of factors that have affected its original appearance. Thus, what can be seen today in Pompeii is not only the result of having been buried by volcanic debris, but also the work of centuries of private excavators and professional archaeologists—and even the misdeeds of treasure hunters—who have plundered, excavated, rebuilt, and conserved the ancient city and its most remarkable private house.