Features

Searching for the Comanche Empire

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

They called themselves Numunu, “the people,” and for centuries they had been hunter-gatherers living in small camps in the Rocky Mountains. But sometime before 1701, when they were first documented by the French on a map of the High Plains, the Numunu left the mountains and encountered horses, possibly trading for them with their linguistic cousins, the Ute, or the Pueblo people of northern New Mexico. By the mid-eighteenth century, they were known as Comanche, a name derived from the Ute word for “anyone who wants to fight me all the time,” and, on the strength of their unparalleled equestrian skills, they were well on their way to being the dominant Indian nation of the American West. Among the most feared mounted warriors in history, the Comanche forged a nomadic culture that served as a model for other Plains Indians. They ranged from Canada all the way to central Mexico, and carved out a homeland that would come to be known as Comanchería, which included much of modern-day Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Colorado, and which endured until the mid-nineteenth century.

Until now, despite the fact that they controlled a vast amount of territory for almost two centuries, and at one point numbered some 40,000 strong, the Comanche have been virtually ignored by archaeologists. “We thought the Comanche had a culture designed to be invisible and to escape detection,” says Barnard College archaeologist Severin Fowles. “If they made camps that they could strike so that no trace remained for the U.S. cavalry to find a few days later, what hope could archaeologists have of finding them more than 200 years later?” But the recent identification of previously unknown panels of rock art at a Comanche encampment in New Mexico’s Rio Grande Gorge is challenging the idea that they left no physical traces behind.

The discovery coincides with the rise of a new generation of historians, who, together with the Comanche themselves, are rereading colonial records and putting together a revised account of Comanche history. This new view contradicts the image of the Comanche in the popular imagination, which casts them as the most brutally savage of the Plains Indians, whose relentless raiding stalled the expansion of the U.S. frontier for decades. In the new, more nuanced approach to Comanche history, the “Lords of the Southern Plains” are emerging instead as skilled tacticians and diplomats capable of mustering thousands of warriors at one time to advance their political and economic interests.

|

Online Exclusive:

|

Rock Art of Comanche Warriors

|

America's Chinatowns

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

Before the California Gold Rush in the late 1840s, there were perhaps 50 native Chinese people in the United States. Just a few decades later, there were more than 100,000, and seemingly every city, town, and remote mining camp in the West had a Chinatown of its own. Chinese immigrants were exotic curiosities, targets of racism and violence—and an essential part of the labor force that settled the West. They left little written history, but dozens upon dozens of archaeological sites and collections are now enriching our understanding of how the first Chinese Americans negotiated life in a strange and sometimes hostile land.

Most of the nineteenth-century Chinese immigrants came from an area the size of Rhode Island—Taishan County, in the southern province of Guangdong, which had suffered the dual indignities of the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion in the 1840s and 1850s. The opening of trade relations between China and the United States, and the discovery of gold in California, spurred the first surge of immigration. In 1852 alone, more than 20,000 Chinese people passed through San Francisco’s Golden Gate. Many found relative safety, comfort, and job opportunities in Chinatowns, which grew first in the cities and then appeared on the frontier as Chinese laborers pursued work in railroad construction, mining, lumber, agriculture, and other industries. Their population in the United States declined following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited new immigration, and would not rebound until the restrictions were lifted 60 years later, starting a second wave of Chinese immigration that has since brought their numbers north of three million.

Archaeological investigation of Chinatowns and Chinese neighborhoods began in the 1970s, with digs at sites such as Ventura, California, and Lovelock, Nevada. There were more in the 1980s and 1990s: Sacramento, San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, San Jose, and others. But most of this early work was cultural resource management—digs related to construction or roadwork—and generated little analysis or scholarship.

Today, Chinese-American archaeology is changing, with new digs, the rediscovery of old collections, and a push to bring researchers together to share findings. Archaeologists and historians have begun working closely with historical societies and descendant communities, and even collaborating with colleagues in southern China. The picture emerging is of a complex, diverse community that held on to some traditions, selectively adopted aspects of Euro-American culture, and tried to make the most of opportunities.

“One of the things that archaeology is doing for all of Chinese America is giving us a greater understanding of what transpired among people who left no or very little written record,” says Sue Fawn Chung, a historian at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who specializes in Chinese-American history.

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

A Brief Glimpse into Early Rome

Off the Grid

Port of the Pyramids

Hardening Brittle Bones

First American Family Tree

Recreating Nordic Grog

The Goddess' Brewer

Peeping through the Leaves

Clash of the War Elephants

England's Oldest Footprints

Secrets of Bronze Age Cheese Makers

Our Lady of the Lake

Big Data, Big Cities

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

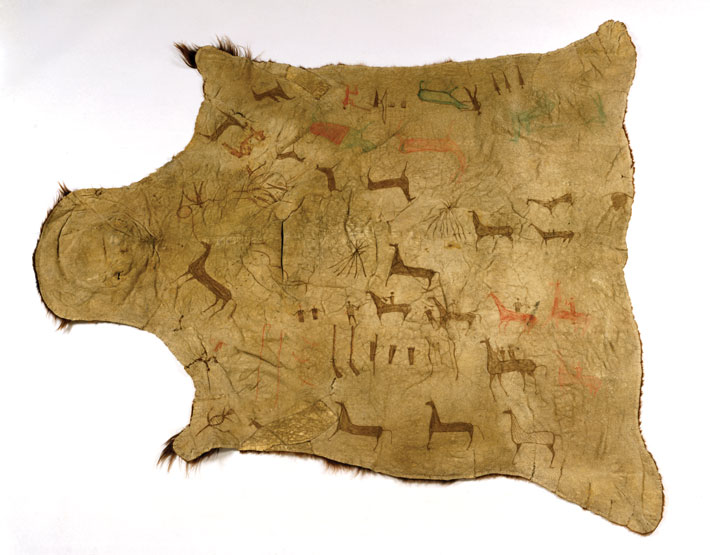

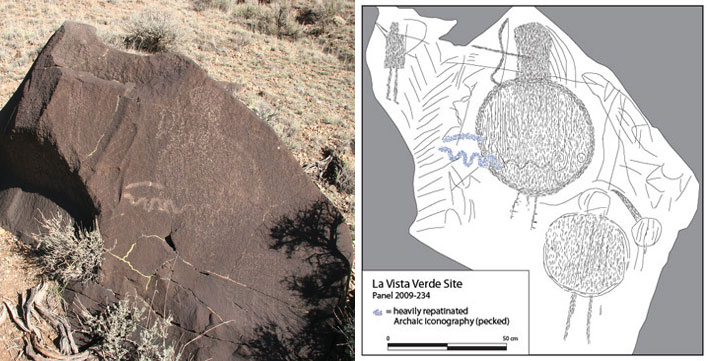

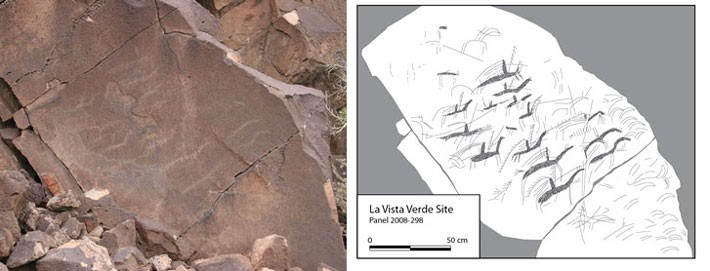

On the boulder, beneath a layer of nineteenth- and twentieth-century graffiti, were unmistakable depictions of horses and ceremonial hide bags, or parfleches, scratched into its surface in a style that Fowles recognized as belonging to Plains Indians. The mysterious triangles they had already recorded were also on the boulder, and it became obvious that they were depictions of tepees. Now that the archaeologists knew what to look for, they began to find the scratch panels everywhere in the canyon. An especially dense cluster was discovered on rugged basalt ridges that surrounded a large flat basin known as Vista Verde, not far from the boulder Dennis had discovered. These panels, which include depictions of horse herds, battles, ritual objects, and whole encampments of tepees, are in some cases within view from a hiking trail that has been used for decades. The barely discernable artwork is a rich archaeological record that no one had ever thought to look for, hidden in plain sight. “It’s hard to find something if you’re not looking for it,” says Fowles.

On the boulder, beneath a layer of nineteenth- and twentieth-century graffiti, were unmistakable depictions of horses and ceremonial hide bags, or parfleches, scratched into its surface in a style that Fowles recognized as belonging to Plains Indians. The mysterious triangles they had already recorded were also on the boulder, and it became obvious that they were depictions of tepees. Now that the archaeologists knew what to look for, they began to find the scratch panels everywhere in the canyon. An especially dense cluster was discovered on rugged basalt ridges that surrounded a large flat basin known as Vista Verde, not far from the boulder Dennis had discovered. These panels, which include depictions of horse herds, battles, ritual objects, and whole encampments of tepees, are in some cases within view from a hiking trail that has been used for decades. The barely discernable artwork is a rich archaeological record that no one had ever thought to look for, hidden in plain sight. “It’s hard to find something if you’re not looking for it,” says Fowles.

In summer 2013, Fowles showed Arterberry a new panel the team discovered not far from the Vista Verde site. Fowles and his group thought it depicted a horse and some other objects, but were uncertain. Upon seeing the panel, Arterberry knew instantly that it showed a galloping horse and a comet in the sky, both heading toward the sun. After looking at historical accounts later, Arterberry would find that in 1680 there was a comet visible by daylight. Looking at the panel in the field, though, he knew that the Comanche who created it was celebrating the connection between the horse, the sun, and a celestial event. “Anthropologists sometimes call us sun worshippers,” says Arterberry. “We’re not, really. We think of the creator as our father, a great deity beyond, who the sun can represent. But to see the sun and the horse and the comet here is very powerful. The creator gave us the horse, and that’s the beginning of the story.”

In summer 2013, Fowles showed Arterberry a new panel the team discovered not far from the Vista Verde site. Fowles and his group thought it depicted a horse and some other objects, but were uncertain. Upon seeing the panel, Arterberry knew instantly that it showed a galloping horse and a comet in the sky, both heading toward the sun. After looking at historical accounts later, Arterberry would find that in 1680 there was a comet visible by daylight. Looking at the panel in the field, though, he knew that the Comanche who created it was celebrating the connection between the horse, the sun, and a celestial event. “Anthropologists sometimes call us sun worshippers,” says Arterberry. “We’re not, really. We think of the creator as our father, a great deity beyond, who the sun can represent. But to see the sun and the horse and the comet here is very powerful. The creator gave us the horse, and that’s the beginning of the story.”