From the Trenches

Peeping through the Leaves

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

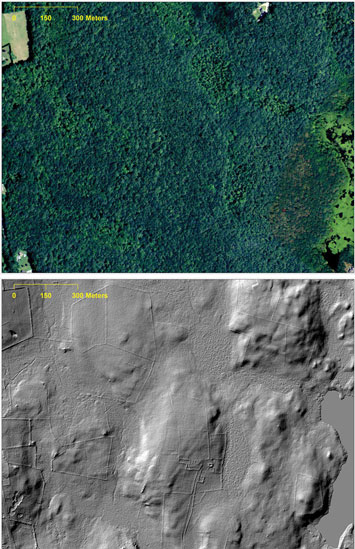

Southern New England’s forests are beloved for the bright colors of their fall foliage, but they also hide much of the rich record of human influence on the historic landscape. Using lidar, which employs lasers to see beneath tree cover, Kate Johnson of the University of Connecticut has been able to peer into the past of the Northeast. “We have identified old stone walls, foundations, dams, mills, and abandoned roads and paths that are obscured in aerial and satellite imagery,” says Johnson. “Being able to see these features on the landscape is exciting because this type of data was never available before.”

Southern New England’s forests are beloved for the bright colors of their fall foliage, but they also hide much of the rich record of human influence on the historic landscape. Using lidar, which employs lasers to see beneath tree cover, Kate Johnson of the University of Connecticut has been able to peer into the past of the Northeast. “We have identified old stone walls, foundations, dams, mills, and abandoned roads and paths that are obscured in aerial and satellite imagery,” says Johnson. “Being able to see these features on the landscape is exciting because this type of data was never available before.”

The Goddess' Brewer

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, April 01, 2014

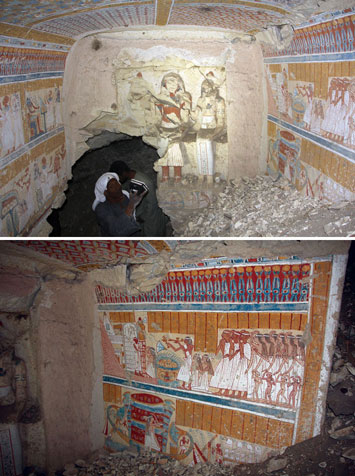

A team of Japanese Egyptologists doing routine cleaning at a New Kingdom necropolis in Luxor accidently uncovered a previously unknown burial chamber decorated with still-vivid murals. “I was surprised to find such a beautiful tomb,” says Waseda University’s Jiro Kondo, who points out that only a handful of chambers with such well-preserved murals have been unearthed at the necropolis. Among the paintings, which date to between 1292 and 1069 B.C., is a depiction of the funeral procession of the tomb’s owner, an official named Khonsuemheb. According to inscriptions in the chamber, he was the chief beer maker of the temple of the mother goddess Mut—an important ritual position. On the ceiling, two figures of Khonsuemheb are painted next to the text of a hymn to the sun god Amun-Ra and a depiction of a solar boat, in which the dead were thought to sail for eternity.

A team of Japanese Egyptologists doing routine cleaning at a New Kingdom necropolis in Luxor accidently uncovered a previously unknown burial chamber decorated with still-vivid murals. “I was surprised to find such a beautiful tomb,” says Waseda University’s Jiro Kondo, who points out that only a handful of chambers with such well-preserved murals have been unearthed at the necropolis. Among the paintings, which date to between 1292 and 1069 B.C., is a depiction of the funeral procession of the tomb’s owner, an official named Khonsuemheb. According to inscriptions in the chamber, he was the chief beer maker of the temple of the mother goddess Mut—an important ritual position. On the ceiling, two figures of Khonsuemheb are painted next to the text of a hymn to the sun god Amun-Ra and a depiction of a solar boat, in which the dead were thought to sail for eternity.

First American Family Tree

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

The burials of two boys—each found decades ago and thousands of miles apart, but recently subjected to genetic analysis—are helping settle the matter of where the first residents of the Americas came from.

The burials of two boys—each found decades ago and thousands of miles apart, but recently subjected to genetic analysis—are helping settle the matter of where the first residents of the Americas came from.

A lab at the University of Copenhagen, led by geneticist Eske Willerslev, has sequenced the genome of a four-year-old boy whose remains were found near the Siberian village of Mal’ta in the 1920s. Dating back 24,000 years, the boy’s DNA was found to be closely related to that of modern Native Americans, suggesting that some of the Mal’ta people’s descendants migrated to the New World. Researchers were surprised that he was significantly related to Europeans, as well as South and Central Asians, but not to East Asians, who have long been known to be connected to Native Americans. The scientists believe that today’s Native Americans are a mixture of the Mal’ta and East Asians they encountered en route from Siberia to the Americas. “The genetics tell us about homelands,” says Mike Waters, a Texas A&M University archaeologist involved in the research, “but it doesn’t tell us about routes.”

Across the Bering Strait, the remains of a one- to two-year-old boy, called Anzick boy, discovered in western Montana more than 45 years ago, are the oldest known burial in the United States, dating to 12,500 years ago. The same Danish lab studied his genome and found that he is a direct ancestor of all modern Native American populations from Mexico to Chile. The boy is also closely, but less directly, related to tribes in Canada and the Arctic. However, because of distrust between the U.S. Native American community and scientists, not enough DNA of American tribes is available to determine their relation to the boy. Waters predicts that “a large chunk of Native Americans in the U.S. will show a strong direct ancestry to the Anzick boy.”

Willerslev says that sequencing more ancient genomes from around the Americas might eventually uncover more detailed migration patterns. “We all have years of work ahead of us if we would like to understand the full picture of the early peopling of the Americas,” he says.

Recreating Nordic Grog

By KATHERINE SHARPE

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

The woman, dead at 30, was buried 1,900 years ago in an oak log near Juellinge, Denmark. Interred with her was a long-handled bronze strainer that still held residue of a fermented drink she may have been meant to enjoy in the afterlife.

The woman, dead at 30, was buried 1,900 years ago in an oak log near Juellinge, Denmark. Interred with her was a long-handled bronze strainer that still held residue of a fermented drink she may have been meant to enjoy in the afterlife.

Now the ingredients and even the flavor of that drink, a “grog” made from local fruits, grains, and herbs mixed with grape wine from southern Europe, are becoming clearer. University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Patrick McGovern has applied biomolecular techniques to organic residue taken from four ancient Scandinavian artifacts, including the woman’s strainer, a clay jar, and pieces of Roman bronze drinking sets, dating to between 1500 B.C. and A.D. 200.

Using a method called solid phase micro-extraction, McGovern found volatile organic compounds that are biomarkers for ingredients such as lingonberry, bog cranberry, rye, barley, juniper, birch, pine, bog myrtle, and yarrow. Tandem mass spectrometry then showed the presence of tartaric acid, the biomarker for wine.

“This work is the first to prove that wine was being traded from the south to the north at this time,” says McGovern. It has also created a detailed, consistent picture of ancient Scandinavia’s preferred beverage of distinction. McGovern is working with Delaware’s Dogfish Head Brewery—as he has on previous concoctions based on ancient residues—to create a modern rendition of the sour, fruity, herbaceous grog.

Hardening Brittle Bones

By KATHERINE SHARPE

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

Just like the bones of living people with osteoporosis, human remains in the archaeological record can lose bone mass over time. These samples usually require treatment with plastic fillers before they can be moved and studied.

Just like the bones of living people with osteoporosis, human remains in the archaeological record can lose bone mass over time. These samples usually require treatment with plastic fillers before they can be moved and studied.

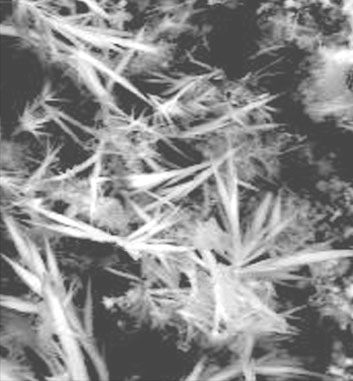

A team of chemists at the University of Florence has devised a novel alternative that uses a chemical reaction to return lost minerals, such as calcium, to fragile old bones. The scientists treated fragments of degraded bone dating from A.D. 1000–1400 with a solution of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles in alcohol. Over several days, the nanoparticles reacted with airborne carbon dioxide and traces of collagen in the bone to form needlelike crystals of aragonite, a hard variant of calcium carbonate that forms naturally in seashells and corals. The crystals left the bones—in this case a saint’s relics from the Basilica of San Clemente in Rome—smoother, whiter, and much stronger.

The method, says study coauthor Luigi Dei, requires further investigation. Unlike the use of plastic fillers to shore up bone, this process is likely irreversible. Once perfected, however, it could be of use wherever archaeologists encounter brittle bones.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

A Brief Glimpse into Early Rome

Off the Grid

Port of the Pyramids

Hardening Brittle Bones

First American Family Tree

Recreating Nordic Grog

The Goddess' Brewer

Peeping through the Leaves

Clash of the War Elephants

England's Oldest Footprints

Secrets of Bronze Age Cheese Makers

Our Lady of the Lake

Big Data, Big Cities

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement