America's Chinatowns

Culture

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

Nineteenth-century Chinese immigrants were usually regarded with deep suspicion by Euro-Americans. Their goods were considered strange, their women immoral, their neighborhoods dangerous, their food unsavory. The first studies of their material culture in the 1970s and 1980s described early Chinatowns as insular, traditional, and resistant to change. These early archaeological studies focused on the idea, long abandoned by historians, of acculturation—that is, how much the Chinese were assimilating American culture. “I think that the way we thought about cultural change was a little narrow,” says Barbara Voss, a Stanford University archaeologist who leads the study of the Market Street Chinatown collection in San Jose.

Archaeological thinking has since evolved, and the relationship between Chinese immigrants and American culture is now known to be much more than a one-way street toward “Americanness.” Chinese-American culture was shaped by tradition, connections to mainland China, institutional segregation and racism, local circumstances, and a complex process of adaptation and selective accommodation.

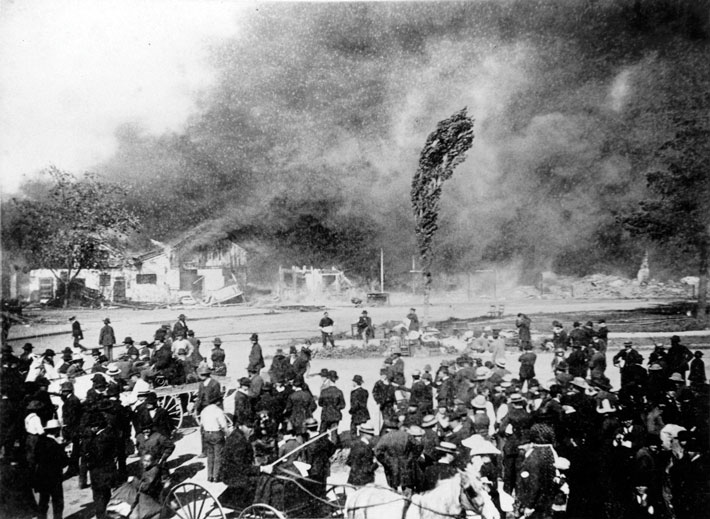

Examples of this complexity come from a number of projects. Market Street Chinatown in San Jose was destroyed in an arson fire in 1887. Anti-Chinese sentiment was high, and arson, beatings, and even murder were not uncommon. The burn layer preserved the site, which was excavated about a hundred years later. The collection, however, was packed away, only to be rediscovered in a storage room in 2001 by archaeologist Rebecca Allen of private cultural-management firm ESA—all 451 boxes of it—who brought it to Voss’ attention. Analysis of the collection (some 50,000 artifacts to date) continues, but has so far revealed a community that was hardly isolated. A rich mixture of Asian, British, and American household goods shows that though it was an ethnic neighborhood, its borders were porous, and its population diverse, mobile, and adaptable. “It’s very clear culture is not a zero-sum game,” Voss says. “People were not choosing between tradition and innovation.”

Examples of this complexity come from a number of projects. Market Street Chinatown in San Jose was destroyed in an arson fire in 1887. Anti-Chinese sentiment was high, and arson, beatings, and even murder were not uncommon. The burn layer preserved the site, which was excavated about a hundred years later. The collection, however, was packed away, only to be rediscovered in a storage room in 2001 by archaeologist Rebecca Allen of private cultural-management firm ESA—all 451 boxes of it—who brought it to Voss’ attention. Analysis of the collection (some 50,000 artifacts to date) continues, but has so far revealed a community that was hardly isolated. A rich mixture of Asian, British, and American household goods shows that though it was an ethnic neighborhood, its borders were porous, and its population diverse, mobile, and adaptable. “It’s very clear culture is not a zero-sum game,” Voss says. “People were not choosing between tradition and innovation.”

During excavations in Sacramento, Adrian Praetzellis of Sonoma State University found a specific instance of how the Chinese selectively, even strategically, adopted American goods. Chinese agents—bilingual businessmen who worked with Americans and helped Chinese laborers find work—were common in urban Chinatowns. In what was once the home of an agent, Praetzellis found both Chinese ceramics and British pieces, especially large serving dishes. According to historical sources, agents held open houses with local businessmen and politicians to show that Chinatown was a reliable place to conduct business. At these banquets, Chinese food was served but—as Praetzellis’ finds show—probably on British servingware. The British ceramics were a nod to guests rather than a sign of assimilation. “It had little or nothing to do with culture change itself,” says Praetzellis. “It had to do with intelligent manipulation of what could be a difficult, even dangerous, situation.” Interestingly, the ceramics include pieces of willow pattern, an iconic nineteenth-century British print that itself had been adapted from a native Chinese pattern and mass-produced in England.

Euro-American culture was not the only influence on Chinese communities. At work camps, laborers from different ethnic backgrounds often lived and worked side by side. At a cannery site in Canada, for example, Doug Ross of Simon Fraser University is examining the differences and similarities between Chinese and Japanese work camps. Furthermore, many neighborhoods considered “Chinatowns” were also home to other marginalized or segregated populations—such as other Asians, African Americans, Native Americans, Portuguese and German immigrants, and even white prostitutes—who found safety, community, a functional economy, and less discrimination or judgment.

Euro-American culture was not the only influence on Chinese communities. At work camps, laborers from different ethnic backgrounds often lived and worked side by side. At a cannery site in Canada, for example, Doug Ross of Simon Fraser University is examining the differences and similarities between Chinese and Japanese work camps. Furthermore, many neighborhoods considered “Chinatowns” were also home to other marginalized or segregated populations—such as other Asians, African Americans, Native Americans, Portuguese and German immigrants, and even white prostitutes—who found safety, community, a functional economy, and less discrimination or judgment.

Labor

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

The Chinese first migrated to the West for the same reason most everyone else did: a shot at “Gold Mountain.” As their reputation for hard work (at low wages) grew, more Chinese came and found jobs on the railroads. Though Chinese immigrants worked in other professions, at the peak of railroad construction in the 1860s, up to 90 percent of the labor force was Chinese. They dug trenches and tunnels, built grades, and laid track from Utah to California, through the same country that had famously claimed the lives of the pioneer Donner Party just 20 years earlier. “The Transcontinental Railroad, arguably one of the most significant engineering feats in North American history, was constructed largely by Chinese workers,” says Stanford’s Voss. “It’s a dramatic example of the role that workers play in building countries and societies.”

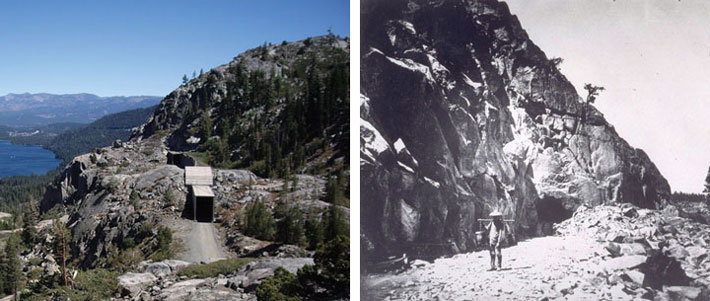

Many of the camps that housed Chinese railroad workers were temporary and have long been forgotten. But between 1865 and 1869, the Central Pacific Railroad pushed through Donner Pass in the High Sierras. At 7,000 feet, sometimes with up to 40 feet of snow pack, laborers, many of whom were Chinese, dug seven tunnels through solid rock. The work took four years, so some encampments there were more established and longer-lived than those elsewhere. John Molenda, a graduate student at Columbia University, has surveyed of a number of these camps, and Rebecca Allen and Scott Baxter of ESA studied one at Summit Pass in detail. “We wanted to know what they were bringing there to make themselves feel like they were at home,” says Allen.

Because tools and personal items probably traveled with the workers, the remains at these sites include some stone foundations and an array of potsherds, gambling pieces, and opium paraphernalia (perhaps used to treat injuries, aches, and pains). At the Summit site, Allen found the remains of a large roasting hearth, evidence of communal meals that may have helped build social bonds. Gambling pieces served a similar purpose, says Molenda. These men were away from their families or the relative comforts of a Chinatown for years at a time, and gambling was a way to create community. Besides, he adds, they wouldn’t have had much to lose: Chinese immigrants sent around two-thirds of their wages back home. According to Molenda, this sense of community, combined with a distinctly Chinese sense of duty and sacrifice, made them particularly effective and sought-after laborers. “They did as much as they could to make themselves as comfortable as possible within the constraint that what they were doing was not about having fun,” says Molenda.

They were so effective, in fact, that many American investors moved specific work gangs onto other projects after the completion of the railroad, and even sometimes protected them during surges of anti-Chinese sentiment. To the capitalists, the Chinese were a cheap, easily controlled labor force. To keep them that way, most investors supported anti-Chinese legislation, which thwarted any social mobility.

They were so effective, in fact, that many American investors moved specific work gangs onto other projects after the completion of the railroad, and even sometimes protected them during surges of anti-Chinese sentiment. To the capitalists, the Chinese were a cheap, easily controlled labor force. To keep them that way, most investors supported anti-Chinese legislation, which thwarted any social mobility.

Much of this recent research is coming together in the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University, a cross-disciplinary effort involving historians, archaeologists, and other scholars. The project aims to create a digital archive of research materials, organize events and conferences, and make connections with institutions in southern China to unify the study of the railroad workers. According to Voss, archaeological director of the project, it is an opportunity for archaeologists in the field to examine new methods for studying a mobile, rapidly moving population. “This is a good project for archaeology,” she says. “This forces us to think differently about our data.”

Food

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

It doesn’t take a connoisseur to know that much of the Chinese food sold in the United States today is hardly the same as traditional Chinese cuisine. We can think of it as Chinese-American food, and its roots likely lie in the kitchens, restaurants, and hearths of nineteenth-century Chinatowns in the West.

Since most of the early Chinese immigrants came from southern China, their cuisine was based on the Cantonese food cooked in Guangdong, mostly rice, vegetables, and pork or fish. The American populace vilified Chinese food as smelly, suspect, and unhealthy. The Chinese cooked their traditional food using both imported ingredients and local substitutes, and catered to local tastes when they had to. “It is fairly similar to other immigrant food situations around the world and in the past,” says Ryan Kennedy, a graduate student at Indiana University who is studying the subject.

The collection from Market Street Chinatown in San Jose includes around 140 soil samples taken from what were probably food storage areas. Stanford’s Voss recently sent samples to Linda Scott-Cummings of the PaleoResearch Institute in Golden, Colorado, to have them analyzed for seeds, pollen, and phytoliths (small pieces of silica that form in plant tissues). There was evidence of rice, as one might expect, but there were also signs of wheat, barley, and millet, which might have been used to make northern Chinese–style noodles.

Scott-Cummings also found evidence of a huge range of vegetables—some familiar to Chinese cooking (bitter melon and jujube, also known as a Chinese date) and some new (gooseberry, walnut), as well as indications of interaction between San Jose’s Chinese and Hispanic populations (corn and tomatillo). Among the standout finds was pollen from agave. Young agave buds look much like lily buds, which are used in traditional Chinese dishes. In fact, Scott-Cummings has observed pollen from other members of the lily family at Chinese sites in Wyoming and Montana, suggesting that local populations often sought out substitutions for this cherished food item. “When you’re living on a different continent, you get whatever you can,” she says.

At other sites, archaeologists have found that the Chinese ate much more beef in the Unites States than they would have in China, where cows were too valuable as beasts of burden to be eaten. “It would have been a departure from what they were eating in China,” says Kennedy. “People are trying new things.”

Health

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

Life would have been hard for most Chinese immigrants in the American West, especially itinerant workers. Ryan Harrod of the University of Alaska Anchorage recently excavated 13 sets of skeletal remains from a Chinese graveyard at Carlin, Nevada, the district terminus for the Central Pacific Railroad. Such graves are rare, as remains were usually sent home to China. The individuals buried at Carlin had several signs of poor nutrition. They also showed evidence of years of grueling manual labor: highly developed muscle attachment points and joints with signs of deterioration. There was also blunt force trauma, from broken bones to a fatal head wound, which reflects the constant threat of physical violence they faced. “In general, just being Chinese at a time when there’s anti-Chinese sentiment in a fairly rural community in the West probably wasn’t that good a situation,” says Harrod.

Life would have been hard for most Chinese immigrants in the American West, especially itinerant workers. Ryan Harrod of the University of Alaska Anchorage recently excavated 13 sets of skeletal remains from a Chinese graveyard at Carlin, Nevada, the district terminus for the Central Pacific Railroad. Such graves are rare, as remains were usually sent home to China. The individuals buried at Carlin had several signs of poor nutrition. They also showed evidence of years of grueling manual labor: highly developed muscle attachment points and joints with signs of deterioration. There was also blunt force trauma, from broken bones to a fatal head wound, which reflects the constant threat of physical violence they faced. “In general, just being Chinese at a time when there’s anti-Chinese sentiment in a fairly rural community in the West probably wasn’t that good a situation,” says Harrod.

Daily life might have been better in more established Chinatowns, but the Chinese still found themselves disadvantaged. “They were often denied access to public healthcare facilities and denied treatment by doctors,” says archaeologist Sarah Heffner, who examined seven collections of Chinese-American healthcare-related artifacts for her dissertation at the University of Nevada, Reno. In the collection from Lovelock, Nevada, at the Nevada State Museum, Heffner found more than 100 health-related artifacts. She found herbal materials used in Chinese medicine, such as turtle carapace, cuttlefish cuttlebones, snake bones, and bobcat bones (perhaps a local substitution for tiger bones, prized in traditional Chinese medicine).

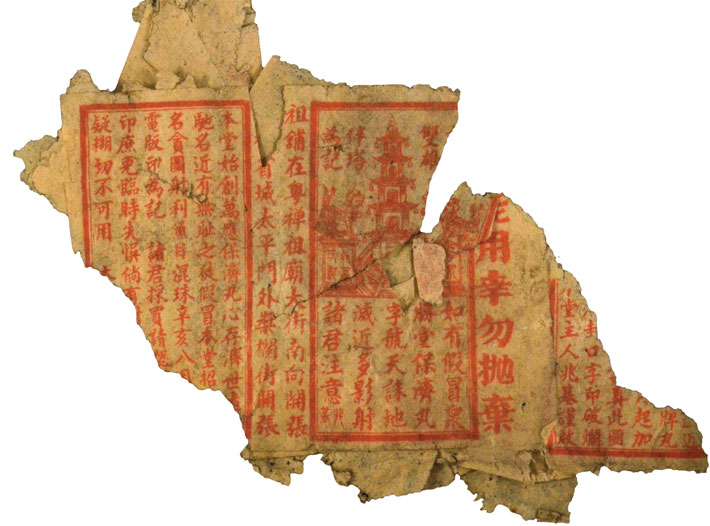

There was also packaged Chinese medicine. One embossed single-dose vial had the name of a drugstore in Hong Kong and specified that it contained “deer’s tail,” “testes and penis of ursine seal,” and “tonify the kidney pills”—all associated with kidney health and treatment of impotence or premature ejaculation. The paper wrapper from another container was labeled “bao ji wan,” or “pills of relief,” and had a written warning that any attempts to copy the contents would result in a curse on the counterfeiter’s family.

There was also packaged Chinese medicine. One embossed single-dose vial had the name of a drugstore in Hong Kong and specified that it contained “deer’s tail,” “testes and penis of ursine seal,” and “tonify the kidney pills”—all associated with kidney health and treatment of impotence or premature ejaculation. The paper wrapper from another container was labeled “bao ji wan,” or “pills of relief,” and had a written warning that any attempts to copy the contents would result in a curse on the counterfeiter’s family.

In the Lovelock collection Heffner also saw Euro-American medicines, primarily bottles containing popular patent medicines such as Sloan’s Family Liniment and Perry Davis’s Vegetable Painkiller. Like the packaged Chinese medicines, these purported cure-alls would have been cheap and practical. “The list of ailments they treat goes on and on and on,” says Heffner. The use of both traditional Chinese treatments and American patent medicines is indicative of a lack of access to more formal healthcare. Not to mention that American patent medicines had a certain popularity because they could be up to 40 percent alcohol and exempt from taxes on spirits.

Single-dose vials like the ones that Heffner studied are common at Chinese sites in the West. Ray von Wandruszka, a chemist from the University of Idaho, is the first to look inside such vials. “Some still had stuff in them,” he says. One vial from Market Street Chinatown in San Jose contained a bright red residue that turned out to be cinnabar, a sulfide of mercury used to treat infections in Chinese medicine. “It’s really toxic, by the way,” von Wandruszka says. Another contained magnetite, used to make an elixir to “anchor and calm the spirit—relieve restlessness, palpitations, insomnia, tremors—improve hearing and vision—combat chronic asthma,” according to a modern sales pitch. These treatments are known as “stone drugs,” pure or mixed mineral powders, and many are still available online today.

Single-dose vials like the ones that Heffner studied are common at Chinese sites in the West. Ray von Wandruszka, a chemist from the University of Idaho, is the first to look inside such vials. “Some still had stuff in them,” he says. One vial from Market Street Chinatown in San Jose contained a bright red residue that turned out to be cinnabar, a sulfide of mercury used to treat infections in Chinese medicine. “It’s really toxic, by the way,” von Wandruszka says. Another contained magnetite, used to make an elixir to “anchor and calm the spirit—relieve restlessness, palpitations, insomnia, tremors—improve hearing and vision—combat chronic asthma,” according to a modern sales pitch. These treatments are known as “stone drugs,” pure or mixed mineral powders, and many are still available online today.

Women

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, April 08, 2014

In the 1850s and 1860s, as much as 90 percent of the population of California—not including Native Americans—was male. This imbalance was temporary for Euro-Americans, but not for the Chinese. Most of the immigrants were men, and American employers preferred an all-male workforce. Anti-Chinese sentiment and the legislation that grew from it exacerbated the gender problem. The Page Act of 1875 outlawed the immigration of “undesirables,” and because Chinese women were stereotyped as prostitutes, it effectively barred them from entry. In addition, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prevented Chinese men from sponsoring the immigration of their wives and families. It was, essentially, American policy that Chinese men not produce natural-born Chinese-Americans. “This was really an American government policy enforced upon the Chinese to create an unnatural bachelor society,” says Sue Fawn Chung, a University of Nevada, Las Vegas, historian.

In the 1850s and 1860s, as much as 90 percent of the population of California—not including Native Americans—was male. This imbalance was temporary for Euro-Americans, but not for the Chinese. Most of the immigrants were men, and American employers preferred an all-male workforce. Anti-Chinese sentiment and the legislation that grew from it exacerbated the gender problem. The Page Act of 1875 outlawed the immigration of “undesirables,” and because Chinese women were stereotyped as prostitutes, it effectively barred them from entry. In addition, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prevented Chinese men from sponsoring the immigration of their wives and families. It was, essentially, American policy that Chinese men not produce natural-born Chinese-Americans. “This was really an American government policy enforced upon the Chinese to create an unnatural bachelor society,” says Sue Fawn Chung, a University of Nevada, Las Vegas, historian.

By some estimates, in 1890, Chinese men outnumbered Chinese women by 28 to one in the United States. There were never more than 5,000 Chinese women in the country well into the twentieth century, according to official records, though historians believe they were undercounted by the census. “Generally your husband hid you in the house,” Chung says. There are accounts of some women who had a surprising amount of freedom and success, but their stories seem to be outnumbered by tales of prostitutes, Chinese women probably forced, coerced, or trafficked into sex work. “[Prostitutes] are never absent from the scene,” says Chung. “But we really don’t have any way to gauge the numbers.”

There are few artifacts found at Chinese sites in the West that can be definitively tied to women, though their presence can be inferred from toys that are sometimes found in Chinese neighborhoods, even remote ones. The right site to establish the archaeological signature of nineteenth-century Chinese women has yet to be found.

Chinese men no doubt felt this absence. California was among the states that outlawed marriage between whites and non-whites, so it is no surprise that the Chinese and other marginalized groups, such as Native Americans, might find common ground. At Mono Mills, California, which is being studied by Charlotte Sunseri of San Jose State University, the Chinese laborer community lived side by side with a community of Paiute people. The two groups definitely interacted—Sunseri found Chinese ceramics in Paiute households, while pine nuts and obsidian blades turned up in Chinese homes. It is possible they may even have cohabitated. There are, in fact, historical records of Chinese-Paiute marriages. “They each had their own marginalization and this was a form of agency,” says Sunseri.

Even after the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, setting off a second wave of Chinese immigration, it would be another 20 years or more before the gender ratio normalized among Chinese Americans.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement