From The Trenches

Taking a Dive

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, June 09, 2014

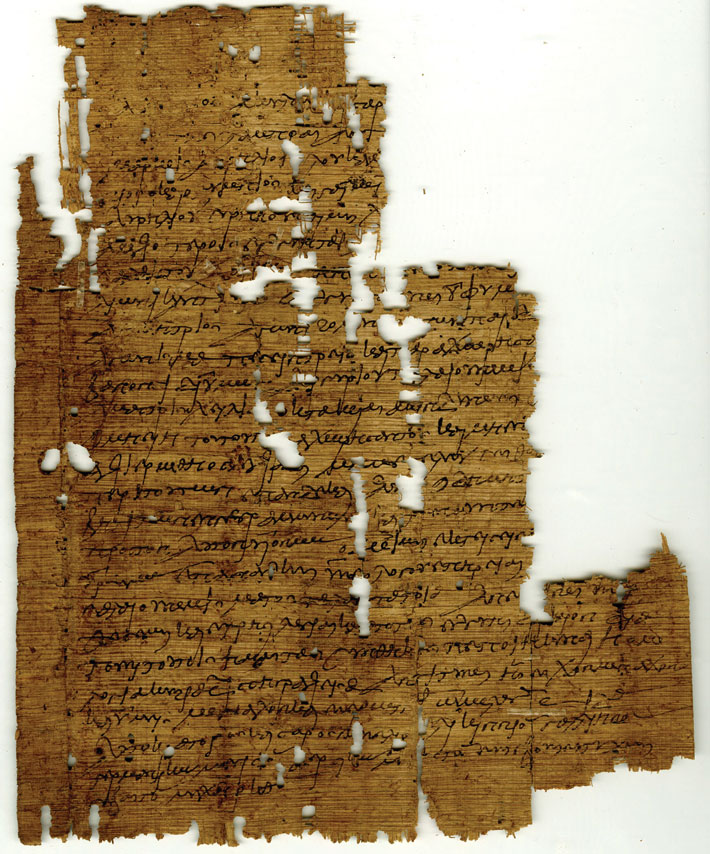

Proof that ancient wrestling wasn’t always on the level has been found among 500,000 fragments of papyri discovered in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, more than a century ago. One fragment, recently scrutinized by historian Dominic Rathbone of King’s College London, concerns a wrestling match between two teenagers, Nicantinous and Demetrius, in A.D. 267. The contract, agreed upon by Nicantinous’ father and Demetrius’ trainers, stipulates that Demetrius must “fall three times and yield.” For his intentional submission, the loser would be paid 3,800 drachmas. Although match fixing is alluded to by some ancient Greek writers, according to Rathbone, “This is the first known papyrological evidence for bribery in an athletic competition.” The agreement also specifies that should the boy renege on the deal, Demetrius’ party would owe a penalty equal to 18,000 drachmas.

Proof that ancient wrestling wasn’t always on the level has been found among 500,000 fragments of papyri discovered in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, more than a century ago. One fragment, recently scrutinized by historian Dominic Rathbone of King’s College London, concerns a wrestling match between two teenagers, Nicantinous and Demetrius, in A.D. 267. The contract, agreed upon by Nicantinous’ father and Demetrius’ trainers, stipulates that Demetrius must “fall three times and yield.” For his intentional submission, the loser would be paid 3,800 drachmas. Although match fixing is alluded to by some ancient Greek writers, according to Rathbone, “This is the first known papyrological evidence for bribery in an athletic competition.” The agreement also specifies that should the boy renege on the deal, Demetrius’ party would owe a penalty equal to 18,000 drachmas.

Childhood Rediscovered

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, June 09, 2014

Thousands of artifacts lie buried just out of students’ sight at Rhode Island College (RIC) in Providence. Researchers from the Rhode Island State Home and School Project have been piecing together the story of the previous, and less fortunate, young people who inhabited the grounds on which the campus stands. Between 1885 and 1979, more than 10,000 dependent and neglected children left their lasting imprint on the landscape as residents of the state’s first public orphanage, still partially visible on the campus’ eastern end. According to RIC anthropologist E. Pierre Morenon, “The Progressive Era women who lobbied for the creation of this place viewed it as a temporary home, or an alternative to the almshouses, poor farms, and asylums of the late 1800s.” The project has spent much of the past decade documenting, preserving, and honoring the childrens’ experiences. Toys were the most common artifacts uncovered, among them marbles, jacks, toy trucks, soldiers, and roller skates. The objects are a sign that, despite their unfortunate circumstances, this young population might still have been able to experience childhood.

Egyptian Style in Ancient Canaan

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, June 09, 2014

Construction of a natural gas pipeline near Tel Shadud, Israel, led to the discovery of a rare 3,300-year-old clay coffin surrounded by pots, bronze artifacts, and animal bones. The finds suggest Egyptian burial rites: The coffin’s sculpted lid is Egyptian in style, the vessels would have held offerings for the gods, and a gold scarab ring in the coffin bears the name of the pharaoh Seti I, who conquered the region in the thirteenth century B.C. Perhaps the remains belonged to an Egyptian living in Canaan, but the pottery was locally produced. This raises the possibility that the interred was a Canaanite either employed by the Egyptian government or wealthy enough to want to emulate one of their burials. The ruling Egyptians exerted a strong influence over the Canaanite upper class at the time.

Construction of a natural gas pipeline near Tel Shadud, Israel, led to the discovery of a rare 3,300-year-old clay coffin surrounded by pots, bronze artifacts, and animal bones. The finds suggest Egyptian burial rites: The coffin’s sculpted lid is Egyptian in style, the vessels would have held offerings for the gods, and a gold scarab ring in the coffin bears the name of the pharaoh Seti I, who conquered the region in the thirteenth century B.C. Perhaps the remains belonged to an Egyptian living in Canaan, but the pottery was locally produced. This raises the possibility that the interred was a Canaanite either employed by the Egyptian government or wealthy enough to want to emulate one of their burials. The ruling Egyptians exerted a strong influence over the Canaanite upper class at the time.

Neanderthal Epigenome

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, June 09, 2014

Modern humans share some 99.7 percent of our DNA with Neanderthals. They are our closest evolutionary cousins, but the differences between us run deeper than that 0.3 percent. Much of what distinguishes the two groups is actually the result of how and when genes are expressed and regulated—essentially, turned on and off. Similar, or even identical, stretches of DNA can produce vastly different traits, such as longer limbs or smaller brains, depending on how and when certain genes are actively producing protein. The study of these processes is known as epigenetics.

Modern humans share some 99.7 percent of our DNA with Neanderthals. They are our closest evolutionary cousins, but the differences between us run deeper than that 0.3 percent. Much of what distinguishes the two groups is actually the result of how and when genes are expressed and regulated—essentially, turned on and off. Similar, or even identical, stretches of DNA can produce vastly different traits, such as longer limbs or smaller brains, depending on how and when certain genes are actively producing protein. The study of these processes is known as epigenetics.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology sequenced Neanderthal DNA in 2010, and now researchers there and at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem are beginning to understand some of the epigenetic differences between humans and Neanderthals. “Studying this is of equal importance to studying the genetic differences,” says Liran Carmel of the Hebrew University.

By looking at the way that Neanderthal DNA chemically degraded over millennia in the ground, the researchers were able to reconstruct how certain molecules, called methyl groups, were attached to the DNA. Methyl groups can help determine how much of a particular protein a gene creates. The research showed that certain Neanderthal genes had different patterns of attached methyl groups, compared with corresponding portions of the modern human genome. As a result, strikingly similar stretches of DNA could produce two very different hominins.

For example, two genes involved in limb development have different patterns of methyl groups, which may be why we have longer arms and legs than Neanderthals did. Similar differences were observed in genes associated with brain development and susceptibility to certain diseases. Carmel believes that as more Neanderthal DNA is analyzed, we will begin to understand the evolutionary changes that created the modern human. “There is a huge potential,” he says. “Studying epigenetic characteristics could be of great importance for zooming in on the properties that have shaped what we are today.”

Ancient Oncology

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, June 09, 2014

In a tomb in northern Sudan, archaeologists have discovered the earliest complete skeleton of a human who suffered from metastatic cancer—cancer that has spread throughout the body. The skeleton, which belonged to a young man who died around 1200 B.C., was riddled with lesions caused by cancer of an unknown organ. A team led by Michaela Binder of Durham University analyzed the lesions using X-rays and digital and scanning electron microscopy, and ruled out alternative causes, such as fungal infection or postmortem changes.

In a tomb in northern Sudan, archaeologists have discovered the earliest complete skeleton of a human who suffered from metastatic cancer—cancer that has spread throughout the body. The skeleton, which belonged to a young man who died around 1200 B.C., was riddled with lesions caused by cancer of an unknown organ. A team led by Michaela Binder of Durham University analyzed the lesions using X-rays and digital and scanning electron microscopy, and ruled out alternative causes, such as fungal infection or postmortem changes.

Cancer has been thought to be a largely modern disease that results in part from longer life spans, exposure to pollutants and unhealthy food, and lack of physical activity. Also, few ancient skeletons bear evidence of cancer, but this may be because the victims died rapidly, before the disease could leave a mark on their bones. The new find adds to evidence that the disease existed, and may even have been common, in antiquity. The site, called Amara West, has been studied since 2008, with excavations in the ancient town and cemeteries. Researchers hope that an understanding of the surrounding community will offer a window into the causes of cancer in ancient populations.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement