Off With Their Heads

September/October 2014

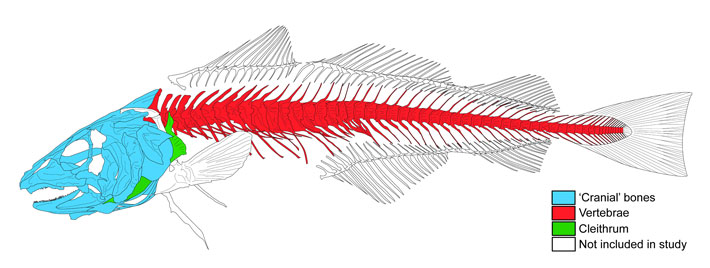

A team of archaeologists has determined that the source of cod consumed in London shifted abruptly in the early thirteenth century when locally caught fish gave way to imports. The evidence for this change is almost 3,000 fish bones from 95 archaeological sites across the city, and specifically their heads. Cranial bones found in London archaeological deposits would have come from locally caught fish, because imported fish arrived without them. At the time, in order to preserve them for long-range shipping, fish were decapitated. Other bones, such as vertebrae, could have come from either local or imported cod. By studying the ratio of cranial bones to vertebrae in archaeological deposits, the researchers could see the relative importance of imports in the city’s cod supply.

A team of archaeologists has determined that the source of cod consumed in London shifted abruptly in the early thirteenth century when locally caught fish gave way to imports. The evidence for this change is almost 3,000 fish bones from 95 archaeological sites across the city, and specifically their heads. Cranial bones found in London archaeological deposits would have come from locally caught fish, because imported fish arrived without them. At the time, in order to preserve them for long-range shipping, fish were decapitated. Other bones, such as vertebrae, could have come from either local or imported cod. By studying the ratio of cranial bones to vertebrae in archaeological deposits, the researchers could see the relative importance of imports in the city’s cod supply.

In deposits dating to before 1200, a relative abundance of cranial bones means that most of the fish consumed in the city was local. But in later deposits the ratio flips, suggesting an increased reliance on imported cod. The ratio also fluctuated in the late fourteenth century, possibly indicating that the Black Death of 1348–1350 interrupted cod imports. Isotopic analysis, which can indicate where the fish came from, provided further evidence for the medieval shift. Bones from the eleventh and twelfth centuries appear to have come from fish from the southern North Sea, close to London. After 1250, however, the majority of bones were associated with fish from far-off regions, such as Norway, Iceland, and the Scottish islands. “What we don’t know is what’s the chicken and what’s the egg here,” says David Orton of the University College of London Institute of Archaeology. “Do we have something that’s affecting the local industry and therefore stimulating the import trade, or do we have the arrival of an import trade which is then damaging the local industry?”

Further research may yield an answer. For example, if the bones of locally caught cod became smaller in the centuries leading up to the shift, that could provide evidence of an impending collapse of the local fishery, which would have created demand for imports.