Top 10 Discoveries of 2010

ROOT

ARCHAEOLOGY's editors reveal the year's most compelling stories

Decades from now people may remember 2010 for the BP oil spill, the Tea Party, and the iPad. But for our money, it’s a lock people will still be excited about the year’s most remarkable archaeological discoveries, which we explore (along with one “undiscovery”) in the following pages.

Decades from now people may remember 2010 for the BP oil spill, the Tea Party, and the iPad. But for our money, it’s a lock people will still be excited about the year’s most remarkable archaeological discoveries, which we explore (along with one “undiscovery”) in the following pages.

This was the year we learned that looters led archaeologists to spectacular and unparalleled royal tombs in both Turkey and Guatemala. An unexpected find brought us closer to Pocahontas, and an underwater archaeological survey in the high Canadian Arctic located the ill-fated HMS Investigator, abandoned in 1853.

Archaeologists weren’t just busy in the field, though. A number of breakthroughs happened in the lab, too. A new radiocarbon dating technique was perfected this year that will allow scientists to date artifacts without harming them. Laboratory analysis of the bones of a close relative of Lucy revealed how early hominins walked. And anthropologists in Germany announced startling news about the Neanderthal genome that might send you scrambling to submit your own DNA for sequencing.

For the third year, we also highlight five threatened sites that remind us of how fragile the archaeological record is. They include an ancient city in Iraq that is eroding into the Tigris and a painted cave in Egypt that’s being slowly destroyed by well-meaning tourists.

But it’s not all bad news out there. One of the most alarming stories this year out of the American Southwest was the news that as part of a cost-cutting measure the Arizona state government closed Homolovi Ruins State Park. The closing raised fears that the park’s significant cluster of Ancestral Puebloan villages dating from A.D. 1260 to 1400 would be left more vulnerable to looters. But at press time we learned the Hopi Tribe signed an agreement with the state to reopen the park. An innovative government-tribal partnership will allow the descendants of the people who once lived at Homolovi Ruins to safeguard its future.

The Tomb of Hecatomnus

Milas, Turkey

Turkish authorities have arrested looters who are suspected of tunneling their way into one of antiquity’s most intriguing tombs. The looters reached the underground chamber, which lies below a temple to Zeus near the town of Milas, by digging in from a nearby house and an adjacent barn. Scholars believe the tomb belonged to Hecatomnus, the fourth-century b.c. ruler of Caria, a kingdom in what is now southwestern Turkey. Hecatomnus was the father of Mausolus, who was buried in the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. (The architectural term mausoleum is derived from the Carian ruler’s name.)

The tomb’s walls are decorated in colored frescos that are in need of immediate conservation. The chamber held an elaborately carved marble sarcophagus with a relief of a bearded, reclining man, believed to depict Hecatomnus. According to journalist Özgen Acar, who has followed the illicit antiquities trade in Turkey for decades, the looters first entered the tomb in the spring of 2008 and were looking for a buyer for the sarcophagus this summer when the authorities moved in. Police arrested 10 suspected looters in a raid in August. At press time, five of the defendants remained in jail awaiting court proceedings. It’s likely the looters had already sold artifacts from the tomb on the black market—shelves in the chamber are now empty.

The tomb’s walls are decorated in colored frescos that are in need of immediate conservation. The chamber held an elaborately carved marble sarcophagus with a relief of a bearded, reclining man, believed to depict Hecatomnus. According to journalist Özgen Acar, who has followed the illicit antiquities trade in Turkey for decades, the looters first entered the tomb in the spring of 2008 and were looking for a buyer for the sarcophagus this summer when the authorities moved in. Police arrested 10 suspected looters in a raid in August. At press time, five of the defendants remained in jail awaiting court proceedings. It’s likely the looters had already sold artifacts from the tomb on the black market—shelves in the chamber are now empty.

Acar believes that while the drilling equipment they used to tunnel into the site may have been sophisticated, the looters were not professionals. “They didn’t have any expertise,” says Acar. “They were locals.” But Turkey’s Culture Minister Ertugrul Gunay believes otherwise. “This is not an ordinary treasure hunt. It’s very organized and it’s obvious that they received economic and scientific help,” he told the Anatolia News Agency, adding that Turkey would investigate the suspects’ foreign connections.

Due to the ongoing police investigation, details about both the case and the discovery are still incomplete. But there is little doubt that the tomb is potentially of great importance for understanding the art and craftsmanship of the Carians, the greatest example of which was the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. Created by the finest architects and sculptors of the day, parts of the mausoleum stood until the late fifteenth century. A statue of Mausolus in the British Museum seems to bear a family resemblance to the bearded man depicted on the sarcophagus.

—Matthew Brunwasser

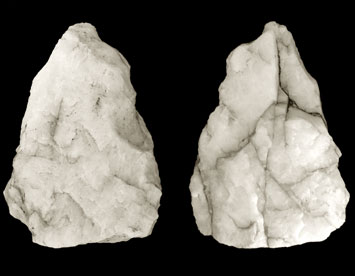

Paleolithic Tools

Plakias, Crete

Aresearch team led by Thomas Strasser of Providence College and Eleni Panagopoulou of the Greek Ministry of Culture announced the discovery of stone tools at two sites on the island of Crete that are between 130,000 and 700,000 years old. The tools resemble those made by Homo heidelbergensis and Homo erectus, showing that one of these early human ancestors boated across at least 40 miles of open sea to reach the island, the earliest indirect evidence of seafaring. “If hominins could move around the Mediterranean before 130,000 years ago, they could cross other bodies of water as well,” says team member Curtis Runnels of Boston University, who helped analyze the tools. “When similar finds on other islands are confirmed, the door will be opened to the re-evaluation of every assumption we have made about early hominin migrations.”

Aresearch team led by Thomas Strasser of Providence College and Eleni Panagopoulou of the Greek Ministry of Culture announced the discovery of stone tools at two sites on the island of Crete that are between 130,000 and 700,000 years old. The tools resemble those made by Homo heidelbergensis and Homo erectus, showing that one of these early human ancestors boated across at least 40 miles of open sea to reach the island, the earliest indirect evidence of seafaring. “If hominins could move around the Mediterranean before 130,000 years ago, they could cross other bodies of water as well,” says team member Curtis Runnels of Boston University, who helped analyze the tools. “When similar finds on other islands are confirmed, the door will be opened to the re-evaluation of every assumption we have made about early hominin migrations.”

—Zach Zorich

Royal Tomb

El Zotz, Guatemala

A deep looters’ trench led archaeologists to a series of amazing, macabre finds beneath the El Diablo pyramid at the modest Maya city of El Zotz. They discovered, just 10 feet beyond where the looters had stopped digging, increasingly bizarre caches, including bowls containing severed fingers, teeth, and a partially cremated infant. “There was mounting evidence of weirdness there,” says Stephen Houston of Brown University, who co-led the excavation with Edwin Roman of the Universities of Texas and San Carlos of Guatemala.

A deep looters’ trench led archaeologists to a series of amazing, macabre finds beneath the El Diablo pyramid at the modest Maya city of El Zotz. They discovered, just 10 feet beyond where the looters had stopped digging, increasingly bizarre caches, including bowls containing severed fingers, teeth, and a partially cremated infant. “There was mounting evidence of weirdness there,” says Stephen Houston of Brown University, who co-led the excavation with Edwin Roman of the Universities of Texas and San Carlos of Guatemala.

The offerings were adjacent to an Early Classic Maya tomb containing the remains of a king dressed as a ritual dancer, complete with a belt adorned with shell “bells” and mammal teeth. “This guy would have made quite a racket,” says Houston. He was buried with the skeletons of four infants, the skulls of two older children, textiles, carvings, and an array of ceramics, including a tamale bowl depicting a peccary.

Based on the position, wealth, and date of the tomb (A.D. 350), researchers believe the king may have been the founder of a dynasty. The tomb is located in a palatial complex high above the central part of the ancient city, next to a spectacular stuccoed pyramid that would have been visible for miles around. “We’re looking at the way in which the Maya create dynasties,” says Houston. “You do it with a loud crash

of cymbals.”

The discovery also shows that even sites hit hard by looters have much to offer. “It’s just a miracle this thing wasn’t looted,” says Houston.

—Samir S. Patel

Early Pyramids

Jaen, Peru

Peru’s towering burial mounds, with their underground chambers and layers upon layers of history, had long been thought to be a distinctive feature of the country’s arid coast.

Peru’s towering burial mounds, with their underground chambers and layers upon layers of history, had long been thought to be a distinctive feature of the country’s arid coast.

But the discovery of two ancient pyramid complexes near the town of Jaen, on the western edge of the Amazon lowlands, shows that monumental architecture had spread across the Andes and well into the jungle thousands of years before the Spaniards arrived. The largest mound, over an acre at its base, was overgrown with vegetation and used by modern townspeople as a dump and latrine before Peruvian archaeologist Quirino Olivera, of the Friends of the Museum of Sipán, began excavating there. He soon found evidence of construction on a massive scale—walls up to three feet thick, ramps, and signs of successive building phases stretching back at least 2,800 years.

“People had assumed monumental architecture never reached the jungle. This discovery shows it did,” says Olivera. “To build these structures, people must have had knowledge of engineering and design, and a large, stable work force. Until now, it was assumed they lived in huts made of tree trunks and leaves.”

At the same pyramid he found the tomb of a high-status man who, at his burial around 800 b.c., was decked out with the shells of some 180 land snails. A layer of snails covered the man’s torso, and more shells adorned his head and limbs. The man was probably a healer or priest of some kind, says Olivera. He found marine mollusk shells in another tomb nearby, testament to the busy trade ties from the coast over the Andes to the jungle. The finds suggest that, along with sophisticated architecture, complex worship had spread far from the coast centuries before once believed.

—Roger Atwood

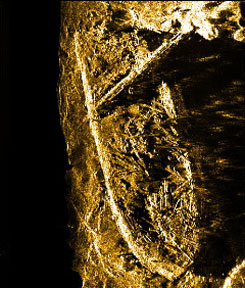

HMS Investigator

Banks Island, Canada

They found the old British ship exactly where it was supposed to be. It hadn’t drifted out to sea, been salvaged by American whalers, or broken up by waves, as various theories had suggested. HMS Investigator—the first ship to sail the westernmost leg of the Northwest Passage—was found last July in Canada’s Mercy Bay under 30 feet of water, but otherwise right where its crew left it in 1853.

The crew, abandoning the ship when it became trapped in pack ice, spent three winters in the area before being rescued and returning to Britain, which made them the first people to travel the passage (by ship, foot, and sled) from end to end. Given the remote location outside Canada’s Aulavik National Park, the ease of the discovery was quite unexpected.

The crew, abandoning the ship when it became trapped in pack ice, spent three winters in the area before being rescued and returning to Britain, which made them the first people to travel the passage (by ship, foot, and sled) from end to end. Given the remote location outside Canada’s Aulavik National Park, the ease of the discovery was quite unexpected.

“We came prepared to search for 16 hours a day for two straight weeks,” says Ryan Harris, an underwater archaeologist with Parks Canada who led the team. “We actually found the ship in just under three minutes.”

Harris used side-scan sonar towed from a 19-foot inflatable boat to locate the well-preserved wreck. At the same time, two more archaeologists documented the remains of the crew’s caches (believed to have influenced the material culture of the local Inuvialuit people) and located the graves of three unlucky seamen who died of scurvy before rescuers arrived.

Harris used side-scan sonar towed from a 19-foot inflatable boat to locate the well-preserved wreck. At the same time, two more archaeologists documented the remains of the crew’s caches (believed to have influenced the material culture of the local Inuvialuit people) and located the graves of three unlucky seamen who died of scurvy before rescuers arrived.

The crew of Investigator never found the two lost British ships, Erebus and Terror, they were sent to find. Harris plans to return to Mercy Bay with dive gear in summer 2011 to take a closer look at Investigator. And to keep an eye out for whatever else might be in those Arctic waters.

—Krista West

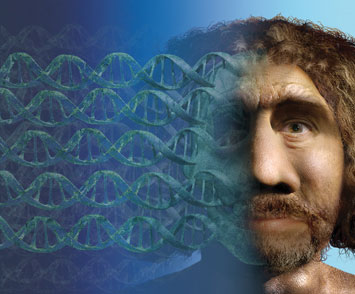

Decoding the Neanderthal Genome

Leipzig, Germany

This past year will always be remembered as the year we found out that the Neanderthals survived and they are us. Following years of tantalizing announcements from the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, a research group led by genetic anthropologist Svante Pääbo completed a first-draft DNA sequence of a Neanderthal. Although this sequence includes only 60 percent of the Neanderthal genome, it does provide some interesting insights into the biology of this distinctive human species. The sequence showed that variations in just one gene might account for the differences in the shape of the skull, rib cage, and shoulder joint between Neanderthals and modern humans.

This past year will always be remembered as the year we found out that the Neanderthals survived and they are us. Following years of tantalizing announcements from the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, a research group led by genetic anthropologist Svante Pääbo completed a first-draft DNA sequence of a Neanderthal. Although this sequence includes only 60 percent of the Neanderthal genome, it does provide some interesting insights into the biology of this distinctive human species. The sequence showed that variations in just one gene might account for the differences in the shape of the skull, rib cage, and shoulder joint between Neanderthals and modern humans.

A major insight came when researchers compared the Neanderthal DNA to the DNA of three modern people (one French, one Han Chinese, and one Polynesian). The team found that all three had inherited between 1 and 4 percent of their DNA from Neanderthals. They also compared the Neanderthal sequence to two African individuals (one Yoruba and one San) and found no indication that they had inherited genes from Neanderthals, who are known to have evolved outside Africa. The research supports the idea that Neanderthals interbred with Homo sapiens between 100,000 and 80,000 years ago as our anatomically modern ancestors left Africa and spread across the globe.

—Zach Zorich

Child Burials

Carthage, Tunisia

Ateam led by University of Pittsburgh physical anthropologist Jeffrey Schwartz has refuted the long-held claim that the Carthaginians carried out large-scale child sacrifice from the eighth to second centuries b.c. The researchers announced their results this year after spending decades examining the cremated remains of 540 children from 348 burial urns excavated in the Tophet, a cemetery outside Carthage’s main burial ground.

Ateam led by University of Pittsburgh physical anthropologist Jeffrey Schwartz has refuted the long-held claim that the Carthaginians carried out large-scale child sacrifice from the eighth to second centuries b.c. The researchers announced their results this year after spending decades examining the cremated remains of 540 children from 348 burial urns excavated in the Tophet, a cemetery outside Carthage’s main burial ground.

Schwartz determined that about half the children were prenatal or would not have survived more than a few days beyond birth, and the rest died between one month and several years after birth. Only a very few children were between five and six years old, the age at which they begin to be buried in the main cemetery. The mortality rates represented in the cemetery are consistent with prenatal and infant mortality figures found in present-day societies. “There is a credible medically and biologically consistent explanation of the Tophet burials that offers an alternative to sacrifice,” says Schwartz. “While it is possible that the Carthaginians may have occasionally sacrificed humans, as did their contemporaries, the extreme youth of the Tophet burials suggests [the cemetery] was not only for the sacrificed, but also for the unborn and very young, however they died. And since at least 20 percent of them weren’t even born when they were buried, they clearly weren’t sacrificed.”

Schwartz also has another type of evidence to support his claim that the Tophet children died of natural causes. “In many societies newborns and very young children are not treated as individuals as older children and adults are,” he says, suggesting that they wouldn’t be considered appropriate for sacrifice. A clue that the Carthaginians didn’t view these children as distinct entities comes from Schwartz’s analysis, which shows that in many urns, there are remains of several different individuals. “There can be four or five of the same right or left cranial bone in the same urn, but there would not be enough other bones to reconstruct the same number of individuals,” says Schwartz. “The remains of multiple children were gathered up, perhaps even from different cremations, and sometimes mixed in with charcoal from the small branches of olive trees used for the funeral pyre.”

—Jarrett A. Lobell

"Kadanuumuu"

Woranso-Mille, Ethiopia

For the last 35 years, the short-legged “Lucy” skeleton has led some scientists to argue that Australopithecus afarensis didn’t stand fully upright or walk like modern humans, and instead got around by “knuckle-walking” like apes. Now, the discovery of a 3.6-million-year-old beanpole on the Ethiopian plains—christened “Kadanuumuu,” or “Big Man” in the Afar language—puts that tired debate to rest. The new fossil demonstrates these early human ancestors were fully bipedal.

For the last 35 years, the short-legged “Lucy” skeleton has led some scientists to argue that Australopithecus afarensis didn’t stand fully upright or walk like modern humans, and instead got around by “knuckle-walking” like apes. Now, the discovery of a 3.6-million-year-old beanpole on the Ethiopian plains—christened “Kadanuumuu,” or “Big Man” in the Afar language—puts that tired debate to rest. The new fossil demonstrates these early human ancestors were fully bipedal.

Many dozens of A. afarensis fossils have been uncovered since Lucy was discovered in 1974, but none as complete as this one. Kadanuumuu’s forearm was first extracted from a hunk of mudstone in February 2005, and subsequent expeditions uncovered an entire knee, part of a pelvis, and well preserved sections of the thorax.

“We have the clavicle, a first rib, a scapula, and the humerus,” says physical anthropologist Bruce Latimer of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, one of the co-leaders on the dig. “That enables us to say something about how [Kadanuumuu] was using its arm, and it was clearly not using it the way an ape uses it. It finally takes knuckle-walking off the table.” At five and a half feet tall, Kadanuumuu would also have towered two feet over Lucy, lending support to the view that there was a high degree of sexual dimorphism in the species.

—Brendan Borrell

1608 Church

Jamestown, Virginia

Archaeologists searching for a men’s barracks at Jamestown, Virginia, site of the first permanent English colony in the New World, have found instead the remains of the earliest Protestant church in North America. Led by Bill Kelso, Historic Jamestowne’s director of archaeology, the team exposed five deep postholes spaced 12 feet apart. Records indicate the wooden church, built in 1608, was 60 feet long. “It didn’t take a mathematical genius to figure out that we had found it,” says Kelso.

Archaeologists searching for a men’s barracks at Jamestown, Virginia, site of the first permanent English colony in the New World, have found instead the remains of the earliest Protestant church in North America. Led by Bill Kelso, Historic Jamestowne’s director of archaeology, the team exposed five deep postholes spaced 12 feet apart. Records indicate the wooden church, built in 1608, was 60 feet long. “It didn’t take a mathematical genius to figure out that we had found it,” says Kelso.

The most prominent building at Jamestown, “the church would have been a statement about how important the colonists considered religion,” says Kelso. Several notable events in the colony’s early history took place there, including Pocahontas’s 1614 marriage to tobacco farmer John Rolfe. Kelso also found that at least six high-status colonists were buried in the church’s chancel, an area near the altar where important rites would have been performed. “Now we can actually point to the spot where Pocahontas got married,” says Kelso. “How often does something like that happen in archaeology?”

—Eric A. Powell

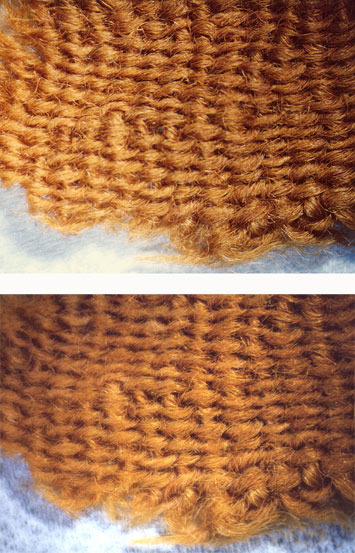

Nondestructive Radiocarbon Dating

College Station, Texas

Precisely dating archaeological artifacts is not as easy or harmless as it might seem. The most common method, radiocarbon dating, requires that a piece of an organic object be destroyed—washed with a strong acid and base at high temperature to remove impurities, and then set aflame. The resulting release of carbon dioxide is fed to an accelerator mass spectrometer, which measures the decay of radioactive carbon 14—the more the carbon 14 has decayed, the older the object is.

Precisely dating archaeological artifacts is not as easy or harmless as it might seem. The most common method, radiocarbon dating, requires that a piece of an organic object be destroyed—washed with a strong acid and base at high temperature to remove impurities, and then set aflame. The resulting release of carbon dioxide is fed to an accelerator mass spectrometer, which measures the decay of radioactive carbon 14—the more the carbon 14 has decayed, the older the object is.

Over the past 20 years, chemist Marvin Rowe of Texas A&M University has developed a nondestructive method for carbon dioxide extraction. In his process, an object is placed in a vacuum chamber and a supercritical fluid—a hybrid gas/liquid—is applied as a solvent (as in dry cleaning). Next, Rowe passes plasma—an “electrically excited ionized gas”—over the artifact, which selectively strips carbon from the sample. “It’s essentially like slowly burning the sample, so we can just oxidize a little off the surface and collect that carbon dioxide,” explains Rowe. This year he further refined the method so it will work on objects coated in sticky hydrocarbons, such as the resins that cover Egyptian mummy gauze.

Thus far, he’s dated samples of wood, charcoal, animal skin, bone from a mummy, and ostrich eggshell. “Everything so far that we’ve tried to do with the nondestructive technique has agreed statistically with regular radiocarbon dating,” Rowe says, “and you basically don’t see any change in the sample.”

R. E. Taylor, a radiocarbon expert at the University of California, Riverside, says Rowe’s technique may have limitations, as items older than 10,000 years will have impurities that the technique may not be able to purge. Archaeologists, meanwhile, are hailing the discovery as one of the most important in decades, particularly for issues surrounding the repatriation of human remains from Native American burials, which modern tribes don’t want to see harmed.

Rowe’s refinement of carbon dioxide extraction dovetails with an update to the radiocarbon calibration curve, which increases the accuracy of radiocarbon dating by accounting for past fluctuations in carbon 14. According to researchers at Queen’s University of Belfast, the new curve doubles the accuracy of dating as well as the age of artifacts on which it can be used, from 25,000 to 50,000 years.

—Nikhil Swaminathan