Features

The Vikings in Ireland

By ROGER ATWOOD

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

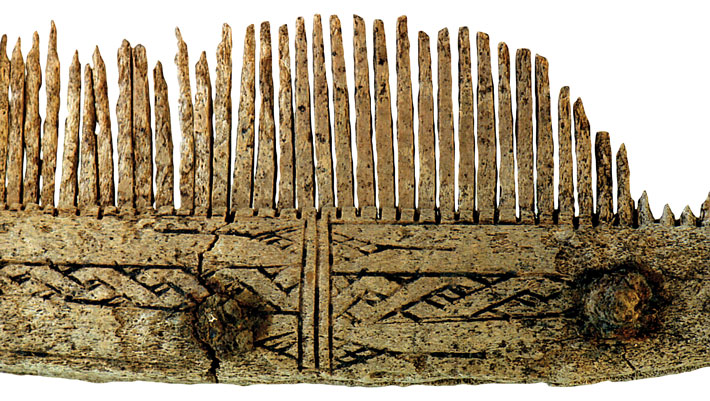

When Irish archaeologists working under Dublin’s South Great George’s Street just over a decade ago excavated the remains of four young men buried with fragments of Viking shields, daggers, and personal ornaments, the discovery appeared to be simply more evidence of the Viking presence in Ireland. At least 77 Viking burials have been discovered across Dublin since the late 1700s, some accidentally by ditch diggers, others by archaeologists working on building sites. All have been dated to the ninth or tenth centuries on the basis of artifacts that accompanied them, and the South Great George’s Street burials seemed to be four more examples.

Yet when excavation leader Linzi Simpson of Dublin’s Trinity College sent the remains for carbon dating to determine their age, the results were “quite surprising,” she says. The tests, performed at Beta Analytic in Miami, Florida, and at Queen’s University in Belfast, showed that the men had been buried in Irish soil years, or even decades, before the accepted date for the establishment of the first year-round Viking settlement in Dublin—and perhaps even before the first known Viking raid on the island took place.

Simpson’s findings are now adding new weight to an idea gaining growing acceptance—that, instead of a sudden, cataclysmic invasion, the arrival of the Vikings in Ireland and Britain began, rather, with small-scale settlements and trade links that connected Ireland with northern European commerce for the first time. And, further, that those trading contacts may have occurred generations before the violent raids described in contemporary texts, works written by monks in isolated monasteries—often the only places where literate people lived—which were especially targeted by Viking raiders for their food and treasures. Scholars are continuing to examine these texts, but are also considering the limitations of using them to understand the historical record. The monks were devastated by the attacks on their homes and institutions, and other contemporaneous events may not have been recorded because there was no one literate available to do so. “Most researchers accept now that the raids were not the first contact, as the old texts suggest,” says Gareth Williams, curator of medieval coinage and a Viking expert at the British Museum. “How did the Vikings know where all those monasteries were? It’s because there was already contact. They were already trading before those raids happened.”

Simpson’s findings are now adding new weight to an idea gaining growing acceptance—that, instead of a sudden, cataclysmic invasion, the arrival of the Vikings in Ireland and Britain began, rather, with small-scale settlements and trade links that connected Ireland with northern European commerce for the first time. And, further, that those trading contacts may have occurred generations before the violent raids described in contemporary texts, works written by monks in isolated monasteries—often the only places where literate people lived—which were especially targeted by Viking raiders for their food and treasures. Scholars are continuing to examine these texts, but are also considering the limitations of using them to understand the historical record. The monks were devastated by the attacks on their homes and institutions, and other contemporaneous events may not have been recorded because there was no one literate available to do so. “Most researchers accept now that the raids were not the first contact, as the old texts suggest,” says Gareth Williams, curator of medieval coinage and a Viking expert at the British Museum. “How did the Vikings know where all those monasteries were? It’s because there was already contact. They were already trading before those raids happened.”

|

Article:

|

Article:

|

The First Vikings

|

Vengeance on the Vikings

|

Rome's Imperial Port

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, February 10, 2015

Twenty miles southwest of Rome, obscured by agricultural fields, woodlands, and the modern infrastructure of one of Europe’s busiest airports, lies what may be ancient Rome’s greatest engineering achievement, and arguably its most important: Portus. Although almost entirely silted in today, at its height, Portus was Rome’s principal maritime harbor, catering to thousands of ships annually. It served as the primary hub for the import, warehousing, and distribution of resources, most importantly grain, that ensured the stability of both Rome and the empire. “For Rome to have worked at capacity, Portus needed to work at capacity,” says archaeologist Simon Keay. “The fortunes of the city are inextricably tied to it. It’s quite hard to overestimate.” Portus was the answer to Rome’s centuries-long search for an efficient deepwater harbor. In the end, as only the Romans could do, they simply dug one.

Although it had previously received little attention archaeologically, over the last decade and half Portus has been the focus of an ambitious project that is rediscovering the grandeur of the port, its relationship to Rome, and the unparalleled role it played as the centerpiece of Rome’s Mediterranean port system. Keay, of the University of Southampton, is currently director of the Portus Project, now in its fifth year, but has been leading fieldwork in and around the site since the late 1990s. He is part of a multinational team investigating Portus’ beginnings in the first century A.D., its evolution into the main port of Rome, and, ultimately, the complex dynamics of the port’s relationship with the city and the broader Roman Mediterranean. The multifaceted project involves a number of institutions, including the United Kingdom’s Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British School at Rome, the University of Cambridge, and the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome.

One of the difficulties the team has faced in addition to the site’s enormous size is its complexity. Portus encompasses not only two man-made harbor basins, but all of the infrastructure associated with a small city, including temples, administrative buildings, warehouses, canals, and roads. Archaeologists have taken many approaches to investigating Portus. “Methodologically, the strategy has been to combine large-scale, extensive work using every kind of geophysical and topographic technique, with excavation reserved for relatively focused areas,” says Keay. “The aim is to try and understand a key area at the center of the port, which could provide a point from which to understand how the port worked as a whole.” The current archaeological research is offering a new understanding of just how Portus’ construction enabled Rome to become Rome.

One of the difficulties the team has faced in addition to the site’s enormous size is its complexity. Portus encompasses not only two man-made harbor basins, but all of the infrastructure associated with a small city, including temples, administrative buildings, warehouses, canals, and roads. Archaeologists have taken many approaches to investigating Portus. “Methodologically, the strategy has been to combine large-scale, extensive work using every kind of geophysical and topographic technique, with excavation reserved for relatively focused areas,” says Keay. “The aim is to try and understand a key area at the center of the port, which could provide a point from which to understand how the port worked as a whole.” The current archaeological research is offering a new understanding of just how Portus’ construction enabled Rome to become Rome.

|

Online Exclusive:

|

Sidebar:

|

Trash Talk

|

Glimpse Into Early Rome

|

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Seismic Shift

Off the Grid

Treasures of Rathfarnham Castle

History's Largest Megalith

Squaring the Circles

Hidden in a Coin Hoard

Autumn of the Master Builder

Buried With Care

New Mosaics at Zeugma

How to Eat a Shipwreck

Tomb of the Jealous Dog

Shackled for Eternity

Treason, Plot, and Witchcraft

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

The fourth Viking excavated at South Great George’s Street was the most intact of the group and revealed the most about their lives and hardships. A powerfully built man in his late teens or early 20s, he stood five foot seven—tall by the day’s standards—with the muscular torso and arms that would come from hard, oceangoing rowing. His bones showed stresses associated with heavy lifting beginning in childhood. Unlike the three other men, he was not buried with weapons. He and one of the other men shared a congenital deformity in the lower spine, perhaps indicating they were relatives. Carbon dating gave a wider range for his lifetime, showing a 95 percent probability that he died between 786 and 955.

The fourth Viking excavated at South Great George’s Street was the most intact of the group and revealed the most about their lives and hardships. A powerfully built man in his late teens or early 20s, he stood five foot seven—tall by the day’s standards—with the muscular torso and arms that would come from hard, oceangoing rowing. His bones showed stresses associated with heavy lifting beginning in childhood. Unlike the three other men, he was not buried with weapons. He and one of the other men shared a congenital deformity in the lower spine, perhaps indicating they were relatives. Carbon dating gave a wider range for his lifetime, showing a 95 percent probability that he died between 786 and 955. In 2005, O’Donovan found two Viking burials under Dublin’s Golden Lane of similar ages to Simpson’s, with a 94 percent probability of death between 678 and 870 for both individuals. One of the burials was an elderly woman, suggesting that Viking family groups, a telltale sign of permanent settlement, were likely established in Dublin earlier than medieval texts had indicated, and perhaps even before the establishment of the longphort. In a separate excavation under Ship Street Great, a few blocks away, Simpson found a Viking corpse with a 68 percent chance of dating from 680 to 775—again, before historical sources say Vikings had even set foot in Ireland. “We know that Vikings started staying over the winter in 841. But now these findings are showing dates before that, and people are starting to wonder what’s going on,” explains Johnson. “They weren’t supposed to be here yet.”

In 2005, O’Donovan found two Viking burials under Dublin’s Golden Lane of similar ages to Simpson’s, with a 94 percent probability of death between 678 and 870 for both individuals. One of the burials was an elderly woman, suggesting that Viking family groups, a telltale sign of permanent settlement, were likely established in Dublin earlier than medieval texts had indicated, and perhaps even before the establishment of the longphort. In a separate excavation under Ship Street Great, a few blocks away, Simpson found a Viking corpse with a 68 percent chance of dating from 680 to 775—again, before historical sources say Vikings had even set foot in Ireland. “We know that Vikings started staying over the winter in 841. But now these findings are showing dates before that, and people are starting to wonder what’s going on,” explains Johnson. “They weren’t supposed to be here yet.” The evidence of an earlier-than-expected Viking presence in Ireland, based as it is on forensic tests conducted on a handful of burials, may seem slight. But seemingly small pieces of evidence can overturn well-established conventions in archaeology. Both Simpson and Johnson stress that more excavations and tests will be needed before anyone can rewrite the history of Viking settlement, and that is years away. Archaeological work in Ireland has been starved of funds and nearly stopped completely after the country’s economic crash of 2008, and it is only now reviving. Williams adds, “There are two possibilities raised by [Simpson’s] work. Either there was Viking activity earlier than we’ve realized in Ireland, or there is something in the water or soil in Dublin skewing the data, and both possibilities need further research.”

The evidence of an earlier-than-expected Viking presence in Ireland, based as it is on forensic tests conducted on a handful of burials, may seem slight. But seemingly small pieces of evidence can overturn well-established conventions in archaeology. Both Simpson and Johnson stress that more excavations and tests will be needed before anyone can rewrite the history of Viking settlement, and that is years away. Archaeological work in Ireland has been starved of funds and nearly stopped completely after the country’s economic crash of 2008, and it is only now reviving. Williams adds, “There are two possibilities raised by [Simpson’s] work. Either there was Viking activity earlier than we’ve realized in Ireland, or there is something in the water or soil in Dublin skewing the data, and both possibilities need further research.” By the dawn of the first century A.D., just before Portus was conceived, Roman territory stretched from Iberia to the Near East, enveloping all the coastal land bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Romans considered the Mediterranean such an innate part of Roman life that they often referred to it simply as Mare Nostrum, or “our sea.” However, paradoxically, as it was located nearly 20 miles inland, Rome was without a suitable nearby maritime port. This obstacle had periodically inconvenienced the city over the course of the previous millennium. In a sense, Rome’s growth had always relied on its capacity to connect with ever-broadening Italian and Mediterranean trade networks. The more Rome expanded, the more it turned to outside resources to feed its population.

By the dawn of the first century A.D., just before Portus was conceived, Roman territory stretched from Iberia to the Near East, enveloping all the coastal land bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Romans considered the Mediterranean such an innate part of Roman life that they often referred to it simply as Mare Nostrum, or “our sea.” However, paradoxically, as it was located nearly 20 miles inland, Rome was without a suitable nearby maritime port. This obstacle had periodically inconvenienced the city over the course of the previous millennium. In a sense, Rome’s growth had always relied on its capacity to connect with ever-broadening Italian and Mediterranean trade networks. The more Rome expanded, the more it turned to outside resources to feed its population. A significant step was taken in 386 B.C. when Rome founded the colony of Ostia at the Tiber’s mouth, some 20 miles away, not only to help supply the growing city with grain and other foodstuffs, but to enhance its connections with the Mediterranean. While Ostia eventually became a significant Roman city and played a major role in imperial Rome’s multifaceted port system, it proved insufficient as the city’s sole port. Although adjacent to the Mediterranean Sea, the site had geographical drawbacks. “Ostia could never handle massive numbers of ships,” says Keay. “It’s a river port, and the river itself is no good. It floods, it’s treacherous at the river mouth, and it’s not really deep enough.”

A significant step was taken in 386 B.C. when Rome founded the colony of Ostia at the Tiber’s mouth, some 20 miles away, not only to help supply the growing city with grain and other foodstuffs, but to enhance its connections with the Mediterranean. While Ostia eventually became a significant Roman city and played a major role in imperial Rome’s multifaceted port system, it proved insufficient as the city’s sole port. Although adjacent to the Mediterranean Sea, the site had geographical drawbacks. “Ostia could never handle massive numbers of ships,” says Keay. “It’s a river port, and the river itself is no good. It floods, it’s treacherous at the river mouth, and it’s not really deep enough.”

The establishment of Portus by Claudius was just the first step in a process that led to the continual expansion and enhancement of the site over the next two centuries. In the early second century A.D., as Rome grew to its greatest territorial extent, the emperor Trajan was responsible for a massive enlargement and reorganization of Portus. Trajan, whose building projects were transforming the city of Rome, turned his architects toward the redevelopment of the existing harbor. As with many Trajanic projects, the goal was not only to provide new functional facilities, but ones that also symbolically celebrated the power and glory of his empire.

The establishment of Portus by Claudius was just the first step in a process that led to the continual expansion and enhancement of the site over the next two centuries. In the early second century A.D., as Rome grew to its greatest territorial extent, the emperor Trajan was responsible for a massive enlargement and reorganization of Portus. Trajan, whose building projects were transforming the city of Rome, turned his architects toward the redevelopment of the existing harbor. As with many Trajanic projects, the goal was not only to provide new functional facilities, but ones that also symbolically celebrated the power and glory of his empire. At the heart of Trajan’s new harbor was another artificially dug basin just east of the existing Claudian basin. Its hexagonal shape, which has become Portus’ most iconic feature, survives today as a private lake for fishing on the estate of Duke Sforza Cesarini. The unusual design, which had no precedents in Roman harbor construction, provided increased functionality, as well as a unique aesthetic signature. The hexagonal basin not only increased Portus’ overall protected harbor space by nearly 600 acres, but the six sides of the new basin expedited the docking and unloading processes. Each of its sides, at a length of almost 1,200 feet, provided ample quayside space for berthing ships and handling cargo.

At the heart of Trajan’s new harbor was another artificially dug basin just east of the existing Claudian basin. Its hexagonal shape, which has become Portus’ most iconic feature, survives today as a private lake for fishing on the estate of Duke Sforza Cesarini. The unusual design, which had no precedents in Roman harbor construction, provided increased functionality, as well as a unique aesthetic signature. The hexagonal basin not only increased Portus’ overall protected harbor space by nearly 600 acres, but the six sides of the new basin expedited the docking and unloading processes. Each of its sides, at a length of almost 1,200 feet, provided ample quayside space for berthing ships and handling cargo.