Horses

Taming the Horse

Thursday, June 04, 2015

The earliest evidence for encounters between humans and horses is found at Paleolithic sites in Eurasia. Butchered horse bones indicate that early peoples used horses as an important source of food. But these swift and spirited animals also clearly fired the human imagination in ways other animals did not. Depictions of them abound in Paleolithic cave art, where horses appear more frequently than any other animal.

In the New World, where it originated, the horse became extinct after the last Ice Age, some 9,000 years ago. A changing climate, and possibly overhunting—by that time humans shared the environment—may have been factors. In much of the Old World, too, horse species disappeared as forest replaced steppe, shrinking their habitat. But on the steppe of what is today Ukraine, Russia, and Kazakhstan, Equus caballus, the species to which modern horses belong, continued to thrive in large numbers. Sometime after 5000 B.C., people in the region who were already familiar with domesticated cattle and sheep may have taken the first step toward taming the horse. Despite being powerful and aggressive, horses had an important advantage over other animals that had already been domesticated: “Horses are easier to feed through harsh winters than sheep or cattle,” says Hartwick College archaeologist David Anthony. “They are well adapted to winter on the steppe, and can break through ice and snow with their hooves to reach winter grass to feed themselves.” There is indirect evidence, such as bone carvings depicting horses together with cattle, that people on the steppe took advantage of this trait and began to maintain herds of horses for winter meat.

There is also evidence that riding horses soon followed domestication. Anthony and his colleague Dorcas Brown have analyzed horse teeth dating to around 3500 B.C. from Kazakhstan and have found wear patterns consistent with the use of rope or leather bits. “I think the first person to climb on a horse was an adolescent or child,” says Anthony. “Some kid probably jumped on the back of a mare as a prank and everyone looked on in astonishment.” But the advantages of horseback riding must have become immediately apparent. It not only made it much easier to manage livestock, but would also have allowed for maintaining larger herds. Riding horses enabled the spread of goods and ideas, not the least of which was horseback riding itself, as never before. The domesticated horse transformed people’s material lives, but it also caused a more subtle, yet radical, change in human culture. “The world opened up to people who could travel on horseback,” says Anthony. “Their sense of distances and what was possible in life would have changed dramatically.”

Horses and the Heavens

Thursday, June 04, 2015

Some of the oldest myths in the Indo-European tradition concern the existence of supernatural or divine horses. The earliest text in Sanskrit, or indeed any Indo-European language—the family that includes most of the main languages of Europe, South Asia, and parts of western and central Asia—is the Rig Veda, a collection of sacred hymns written sometime in the late second millennium B.C., during the Bronze Age. Among its more than 1,000 hymns are prayers and poems appealing to and honoring the gods. At the time the Rig Veda was set down, the myths it references were already centuries, if not millennia, old, but it was during the Bronze Age that Indo-European-speaking peoples began to travel and trade across great distances, carrying with them beliefs that were then communicated across a vast territory, stretching from Asia to Scandinavia.

Archaeological evidence collected in Europe provides the strongest parallels for early Indo-European myths first set down on the Indian subcontinent, says Kristian Kristiansen of the University of Gothenberg. One of the most important of these shared Bronze Age myths is that of the sun cult, wherein the sun’s daily journey is symbolized by a horse drawing a chariot across the heavens. This is also widely interpreted as the journey from death to the afterlife.

In both ancient Greek and Norse mythology, too, there are supernatural horses. The winged stallion Pegasus is the offspring of the god Poseidon and the Gorgon Medusa, from whose neck he was born when she was beheaded by Perseus. After taming Pegasus, the Corinthian hero Bellerophon attempts to ride the horse to the gods’ home on Mount Olympus. But Zeus compels the horse to buck, sending Bellerophon back to Earth as punishment for his pride. Pegasus continues his journey heavenward to live in Zeus’ stables and carry his thunderbolts. Zeus also set Pegasus in the sky as a constellation marking the arrival of spring. Odin, the powerful Norse god of war, poetry, knowledge, and wisdom, also has a divine horse in his service. Renowned for his speed, the eight-legged horse Sleipnir carries Odin on his journeys through the Nine Worlds that are the homelands of the elements found in the Norse worldview—humanity, tribes of gods and goddesses, giants, fire, ice, dwarves, elves, and death.

In both ancient Greek and Norse mythology, too, there are supernatural horses. The winged stallion Pegasus is the offspring of the god Poseidon and the Gorgon Medusa, from whose neck he was born when she was beheaded by Perseus. After taming Pegasus, the Corinthian hero Bellerophon attempts to ride the horse to the gods’ home on Mount Olympus. But Zeus compels the horse to buck, sending Bellerophon back to Earth as punishment for his pride. Pegasus continues his journey heavenward to live in Zeus’ stables and carry his thunderbolts. Zeus also set Pegasus in the sky as a constellation marking the arrival of spring. Odin, the powerful Norse god of war, poetry, knowledge, and wisdom, also has a divine horse in his service. Renowned for his speed, the eight-legged horse Sleipnir carries Odin on his journeys through the Nine Worlds that are the homelands of the elements found in the Norse worldview—humanity, tribes of gods and goddesses, giants, fire, ice, dwarves, elves, and death.

Warhorses

Thursday, June 04, 2015

By the mid-second millennium B.C., the use of horses in warfare had become common throughout the Near East and Egypt. This development was made possible by advances both in the design of chariots, in particular the invention of the spoked wheel, which replaced the solid wooden wheel and reduced a chariot’s weight, and the introduction of all-metal bits, which gave chariot drivers more control over their horses. Though chariot warfare was expensive, and its effectiveness was determined by the durability of the chariots and suitability of the terrain, the vehicles became essential battlefield equipment. According to archaeologist Brian Fagan of the University of California, Santa Barbara, Bronze Age chariots acted largely as mobile archery platforms, with the bulkier four-wheeled ones also being used to carry kings into battle or to allow generals to observe the fighting. Lighter two-wheeled versions, such as those found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, were better suited to carrying a single archer and a driver.

One of the most informative sources for the use of chariot horses in the ancient Near East is a tablet discovered in 1906–1907 in the royal archive at the Hittite site of Hattusa in Anatolia. The “Kikkuli Text,” written in cuneiform script and dating to around 1400 B.C., is named after its author. Kikkuli introduces himself in the first line as a “horse trainer from the land of the Mitanni,” a state in what is now northern Syria and southeastern Turkey. He then describes an approximately 184-day training cycle that begins in the fall, in which he includes instructions for the horses’ feeding, watering, and care, recommending stable rest, massages, and blankets.

One of the most informative sources for the use of chariot horses in the ancient Near East is a tablet discovered in 1906–1907 in the royal archive at the Hittite site of Hattusa in Anatolia. The “Kikkuli Text,” written in cuneiform script and dating to around 1400 B.C., is named after its author. Kikkuli introduces himself in the first line as a “horse trainer from the land of the Mitanni,” a state in what is now northern Syria and southeastern Turkey. He then describes an approximately 184-day training cycle that begins in the fall, in which he includes instructions for the horses’ feeding, watering, and care, recommending stable rest, massages, and blankets.

For nearly a millennium, warhorses were used almost exclusively to pull chariots, but after about 850 B.C. chariotry began to decline. Horses, however, never lost their usefulness in battle. Within about 150 years, cavalry, which is suitable to almost any terrain, virtually replaced chariotry in the Near East, and, eventually, horse-drawn chariots were employed primarily for racing, in ceremonial parades, and as prestige vehicles. In time this happened not only in this region, but across most of Europe as well. The rise of true cavalry was the determining force behind many of the major events that influenced European history, including Charles Martel’s defeat of the Saracens at the Battle of Poitiers in A.D. 732, the creation of the Holy Roman Empire, and the victory of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in A.D. 1066. “I think that the most important development in history with respect to animals was the adoption of the horse as a weapon of war,” says Fagan.

For nearly a millennium, warhorses were used almost exclusively to pull chariots, but after about 850 B.C. chariotry began to decline. Horses, however, never lost their usefulness in battle. Within about 150 years, cavalry, which is suitable to almost any terrain, virtually replaced chariotry in the Near East, and, eventually, horse-drawn chariots were employed primarily for racing, in ceremonial parades, and as prestige vehicles. In time this happened not only in this region, but across most of Europe as well. The rise of true cavalry was the determining force behind many of the major events that influenced European history, including Charles Martel’s defeat of the Saracens at the Battle of Poitiers in A.D. 732, the creation of the Holy Roman Empire, and the victory of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in A.D. 1066. “I think that the most important development in history with respect to animals was the adoption of the horse as a weapon of war,” says Fagan.

Riding into the Afterlife

Thursday, June 04, 2015

Once horses were domesticated, they began to play an important role in funeral rituals. Archaeologists have found horse bones mingled with cow and sheep remains in human burials on the Eurasian steppe dating to as early as 5000 B.C. All the animals were probably sacrificed and eaten during funeral rituals. Later, the increasingly singular role horses played in human lives was reflected in more elaborate burial rites that were practiced by unrelated cultures from China to England. Perhaps the first to accord horses an honored role in burials were the Sintashta people, a sedentary culture that built large fortified settlements south of the Ural Mountains around 2000 B.C. Important members of this society were buried with their chariots and the horses that pulled them. Unlike other livestock that may have been sacrificed and eaten during funeral rites, these horses went with their owners to the afterlife intact.

Once horses were domesticated, they began to play an important role in funeral rituals. Archaeologists have found horse bones mingled with cow and sheep remains in human burials on the Eurasian steppe dating to as early as 5000 B.C. All the animals were probably sacrificed and eaten during funeral rituals. Later, the increasingly singular role horses played in human lives was reflected in more elaborate burial rites that were practiced by unrelated cultures from China to England. Perhaps the first to accord horses an honored role in burials were the Sintashta people, a sedentary culture that built large fortified settlements south of the Ural Mountains around 2000 B.C. Important members of this society were buried with their chariots and the horses that pulled them. Unlike other livestock that may have been sacrificed and eaten during funeral rites, these horses went with their owners to the afterlife intact.

Many steppe cultures that came after the Sintashta also practiced horse burials. In Siberia, the fifth-century B.C. Iron Age Pazyrk people buried their noble dead in huge mounds, accompanied by horses outfitted with cloth saddles and dramatic headdresses. But it was in China that horse burials achieved their most elaborate expression. Excavation of the sixth-century B.C. tomb of Chinese ruler Duke Jing of Qi has revealed the remains of 200 horses, which would have represented a vast fortune. The tomb has not been fully excavated, and some archaeologists estimate it might have held up to 600 horses. This number is only rivaled by representations of horses accompanying the terracotta army discovered in pits near the famed mausoleum of China’s first emperor, Qin Shihuangdi (r. 220–210 B.C.). Archaeologists estimate that 130 chariots were buried there, along with bronze and terracotta depictions of more than 650 horses.

Sport and Spectacle

Thursday, June 04, 2015

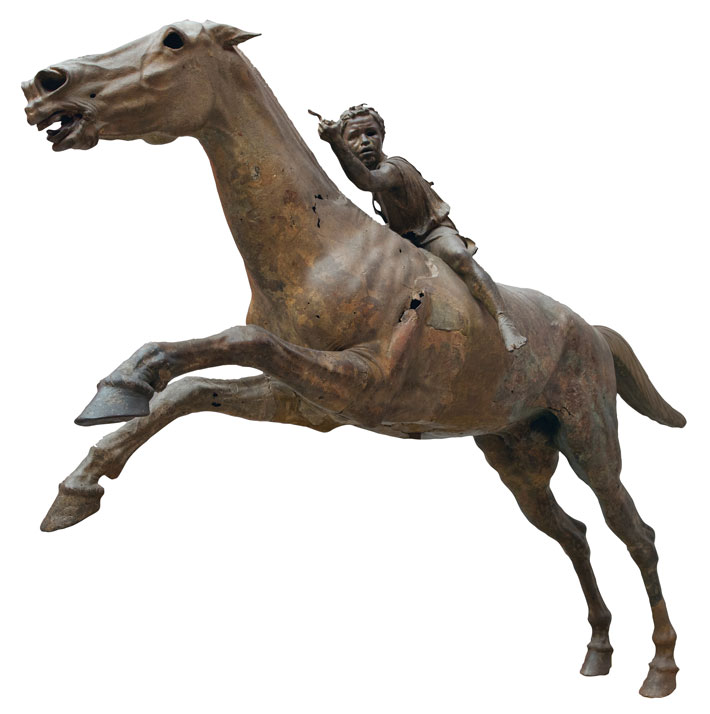

In the Greco-Roman world, racehorses were potent symbols used by both individuals and the state to express power, encourage civic pride, and celebrate special events. For the Greeks, chariot racing likely began sometime around 1500 B.C. and became a central element of their most sacred festivals. A memory of these early contests appears in Homer’s description of the funeral games honoring the fallen warrior Patroclus, during which Greek kings and heroes race once around a tree stump for the prize of a female slave. Perhaps a century after the founding of the Olympics in 776 B.C., chariot and jockeyed races were included in the games. This provided an opportunity for families to display their “hippic”—or horse—wealth as social and political capital, explains historian Donald Kyle of the University of Texas at Arlington.

Yet for the Romans, hippic contests were just as often part of extravagant state-sponsored displays intended to entertain the masses. The historian Livy says that the first and largest Roman hippodrome, the Circus Maximus, was built by Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the legendary fifth king of Rome (r. 616–579 B.C.), in a valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills. Though originally a simple open oval space similar to a Greek hippodrome, the Romans gradually created a massive stadium-style building that, by the first century A.D., could accommodate perhaps as many as 250,000 spectators. While there were certainly other crowd-pleasing events such as gladiatorial contests in ancient Rome, “chariot racing is the earliest and longest-enduring major spectacle in Roman history,” says Kyle.

Yet for the Romans, hippic contests were just as often part of extravagant state-sponsored displays intended to entertain the masses. The historian Livy says that the first and largest Roman hippodrome, the Circus Maximus, was built by Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the legendary fifth king of Rome (r. 616–579 B.C.), in a valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills. Though originally a simple open oval space similar to a Greek hippodrome, the Romans gradually created a massive stadium-style building that, by the first century A.D., could accommodate perhaps as many as 250,000 spectators. While there were certainly other crowd-pleasing events such as gladiatorial contests in ancient Rome, “chariot racing is the earliest and longest-enduring major spectacle in Roman history,” says Kyle.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement