From the Trenches

Open House

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Thursday, June 04, 2015

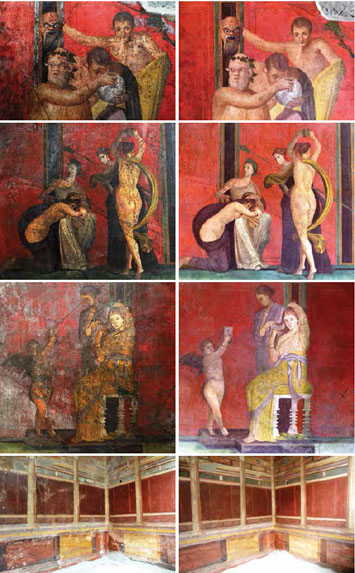

After being closed for the past two years, all 70 rooms of Pompeii’s most famous house, the Villa of the Mysteries, have reopened, revealing to the public for the first time the astonishing results of an extensive restoration and conservation project (“Saving the Villa of the Mysteries,” March/April 2014). Much of the most recent work, begun in 2013, focused on removing the layer of wax that had been used to protect the frescoes in the 1930s. However, it was discovered that the wax had damaged and faded the paintings’ once-vibrant colors. With the wax eradicated and the frescoes cleaned using chemical solutions and lasers, it is now possible to see, for the first time since they were buried by the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, just how remarkable the paintings are. In addition to conserving the frescoes, the researchers also cleaned, repaired, and consolidated the luxurious villa’s walls and floors, both to restore their appearance and to improve the stability of the building from top to bottom.

After being closed for the past two years, all 70 rooms of Pompeii’s most famous house, the Villa of the Mysteries, have reopened, revealing to the public for the first time the astonishing results of an extensive restoration and conservation project (“Saving the Villa of the Mysteries,” March/April 2014). Much of the most recent work, begun in 2013, focused on removing the layer of wax that had been used to protect the frescoes in the 1930s. However, it was discovered that the wax had damaged and faded the paintings’ once-vibrant colors. With the wax eradicated and the frescoes cleaned using chemical solutions and lasers, it is now possible to see, for the first time since they were buried by the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, just how remarkable the paintings are. In addition to conserving the frescoes, the researchers also cleaned, repaired, and consolidated the luxurious villa’s walls and floors, both to restore their appearance and to improve the stability of the building from top to bottom.

Slime Molds and Roman Roads

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, June 04, 2015

Can an acellular slime mold mimic the Roman road network in the Balkans? It’s not a riddle, but the subject of a new study by researchers in Greece and the United Kingdom.

Can an acellular slime mold mimic the Roman road network in the Balkans? It’s not a riddle, but the subject of a new study by researchers in Greece and the United Kingdom.

That slime mold, called Physarum polycephalum, consists of a single large membrane around many cell nuclei, and has drawn the attention of a wide range of scientists because of its uncanny ability to solve almost impossibly complex computational problems.

Through rhythmic contractions of its membrane, called shuttle streaming, the slime mold grows out in search of food. If you put a P. polycephalum into a maze with two food sources in it, over a few days the organism will grow toward the food sources and retract from everywhere else except the shortest path between them. Mathematicians and network analysts call this the “shortest path problem.” When presented with additional food sources, the slime mold forms ever more complex and efficient networks. These “Physarum machines,” as they are known, may help in the understanding of communication, road, and transport networks, which also, over time, come to balance complexity and efficiency.

The new study applied the power of a Physarum machine (and a computer program that simulates its behavior) to landscape-scale archaeology, specifically Roman roads in the Balkans. Researchers placed a P. polycephalum in a petri dish containing 17 little bits of food representing 17 urban centers in the Balkans from the Roman imperial period. The slime mold “imitated rather spectacularly the two main military roads of the area, the Via Egnatia [across Macedonia] and the Via Diagonalis [from central Europe to Constantinople],” says archaeologist Vasilis Evangelidis of the Hellenic Ministry of Education. This was a test case, but future experiments with P. polycephalum might reveal previously unobserved patterns in complex networks of human settlement, trade, and migration.

Finding Lost African Homelands

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, June 04, 2015

During the height of the transatlantic slave trade, from 1500 to 1850, some 12 million people were enslaved, most from West and West Central Africa. Diverse cultures, languages, traditions, and religions were found in these regions, but the ethnic and geographic origins of most of these individuals are lost to history. This is no longer the case for three slaves who were buried on the Caribbean island of St. Martin in the seventeenth century.

During the height of the transatlantic slave trade, from 1500 to 1850, some 12 million people were enslaved, most from West and West Central Africa. Diverse cultures, languages, traditions, and religions were found in these regions, but the ethnic and geographic origins of most of these individuals are lost to history. This is no longer the case for three slaves who were buried on the Caribbean island of St. Martin in the seventeenth century.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen and the Stanford University School of Medicine have employed a new technique for studying fragmented DNA to learn more about where these individuals came from. DNA does not last long in the tropics, but the researchers found small bits of it in tooth roots, which they then subjected to a technique called whole-genome capture. This allowed them to isolate and identify enough DNA to compare with modern samples from West Africa. One of the slaves belonged to a Bantu-speaking population in northern Cameroon, while the other two came from non-Bantu-speaking groups in Nigeria and Ghana. Though they were buried together, these three people may not have had a language in common.

“The findings demonstrate that genomic data can be used to trace the genetic ancestry of long-dead and poorly preserved individuals,” says lead researcher Hannes Schroeder of the Natural History Museum of Denmark, “a finding with important implications for archeology, especially in cases where historical information is missing.”

Neanderthal Necklace

By ZACH ZORICH

Thursday, June 04, 2015

More than 100 years ago, eight eagle talons were excavated from a famous Neanderthal site called Krapina, and subsequently left in a drawer at the Croatian Natural History Museum in Zagreb. Davorka Radovčic recently took over as curator, and she discovered the talons while reexamining the museum’s collections. She noticed several deep cut marks and evidence that the talons had been strung together as a necklace. The talons have been dated to about 130,000 years ago, predating the arrival of Homo sapiens in the area by about 50,000 years. The talon necklace is now thought to be the earliest known symbolic Neanderthal artifact.

More than 100 years ago, eight eagle talons were excavated from a famous Neanderthal site called Krapina, and subsequently left in a drawer at the Croatian Natural History Museum in Zagreb. Davorka Radovčic recently took over as curator, and she discovered the talons while reexamining the museum’s collections. She noticed several deep cut marks and evidence that the talons had been strung together as a necklace. The talons have been dated to about 130,000 years ago, predating the arrival of Homo sapiens in the area by about 50,000 years. The talon necklace is now thought to be the earliest known symbolic Neanderthal artifact.

A Parisian Plague

By DANIEL WEISS

Thursday, June 04, 2015

Several mass graves—one of which includes the remains of at least 150 bodies—have been discovered beneath a Paris supermarket located just a mile from Notre Dame Cathedral. The French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) unearthed the graves in advance of an expansion of the supermarket’s basement.

Several mass graves—one of which includes the remains of at least 150 bodies—have been discovered beneath a Paris supermarket located just a mile from Notre Dame Cathedral. The French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) unearthed the graves in advance of an expansion of the supermarket’s basement.

Based on the largest grave’s placement among other underground features, archaeologists believe it dates to between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries. The people in the grave, men and women of all ages as well as children, appear to have been the victims of a fierce epidemic, most likely plague. The bodies were buried snugly, with children nestled into spaces between adults, says Mark Guillon, a physical anthropologist with INRAP Paris and the French National Center for Scientific Research in Bordeaux. A hospital cemetery consisting largely of individual burials was located nearby, though it is unclear whether there is any connection between the two sets of burials.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

A Spin through Augustan Rome

Off The Grid

The First Toolkit

Anglo-Saxon Jewelry Box

Wrecks of the Pacific Theater

The Environmental Cost of Empire

One Ring to Bind Them

Cosmic Rays and Australopithecines

Bison Bone Mystery

Rome's Earliest Fort

A Parisian Plague

Finding Lost African Homelands

Neanderthal Necklace

Slime Molds and Roman Roads

Open House

World Roundup

Civil War booze, world’s oldest pretzels, Austria’s war camels, coral tombs of the Pacific, and a 2.8-million-year-old human

Artifact

Styling hair in Bronze Age Wales

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement