From the Trenches

Rome's Earliest Fort

By JASON URBANUS

Thursday, June 04, 2015

Archaeologists working outside Trieste, Italy, have discovered what may be the oldest surviving Roman fortification system. An interdisciplinary study used ground-penetrating radar, lidar, and archaeological survey to reveal three Roman forts—one large central camp and two minor outposts—that are the only Roman camps ever identified on Italian soil. The largest of the three, San Rocco, was strategically located across 32 acres of land, with outer and inner networks of ramparts. Dating to the beginning of the second century B.C., the camp predates the previous earliest known examples of Roman encampments, in Iberia. The fort was likely built to support Rome’s conquest of the Istrian Peninsula in 178–177 B.C., and would have been an essential resource in helping Rome secure its unstable borders against the native Celtic population. “These forts are very important in understanding the origins of Roman military architecture, the Roman conquest of the area, and also the origins of modern Trieste,” says Federico Bernardini of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics.

Archaeologists working outside Trieste, Italy, have discovered what may be the oldest surviving Roman fortification system. An interdisciplinary study used ground-penetrating radar, lidar, and archaeological survey to reveal three Roman forts—one large central camp and two minor outposts—that are the only Roman camps ever identified on Italian soil. The largest of the three, San Rocco, was strategically located across 32 acres of land, with outer and inner networks of ramparts. Dating to the beginning of the second century B.C., the camp predates the previous earliest known examples of Roman encampments, in Iberia. The fort was likely built to support Rome’s conquest of the Istrian Peninsula in 178–177 B.C., and would have been an essential resource in helping Rome secure its unstable borders against the native Celtic population. “These forts are very important in understanding the origins of Roman military architecture, the Roman conquest of the area, and also the origins of modern Trieste,” says Federico Bernardini of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics.

Bison Bone Mystery

By ERIC A. POWELL

Thursday, June 04, 2015

In southern Alberta, University of Lethbridge archaeologist Shawn Bubel and her team were excavating a bison kill site dating to 500 B.C. when they encountered something bizarre. Beneath the remains of at least 68 butchered bison, prehistoric hunters had pressed collections of bison bones deep into the earth. “I had my students dig below the bone bed, not expecting to find anything,” says Bubel. “Then we started to see bones shoved down into clay.” Eventually the team unearthed eight of these enigmatic bone structures, which dated to the same time as the bone bed above them. Bubel says that while prehistoric Native Americans were known to use upright bison bones as anvils or to tie down tepees, none of these bones bore the telltale marks of those activities. “It’s a cliché for archaeologists to call things ceremonial when they don’t understand them, but I think in this case that’s really what we have,” says Bubel.

In southern Alberta, University of Lethbridge archaeologist Shawn Bubel and her team were excavating a bison kill site dating to 500 B.C. when they encountered something bizarre. Beneath the remains of at least 68 butchered bison, prehistoric hunters had pressed collections of bison bones deep into the earth. “I had my students dig below the bone bed, not expecting to find anything,” says Bubel. “Then we started to see bones shoved down into clay.” Eventually the team unearthed eight of these enigmatic bone structures, which dated to the same time as the bone bed above them. Bubel says that while prehistoric Native Americans were known to use upright bison bones as anvils or to tie down tepees, none of these bones bore the telltale marks of those activities. “It’s a cliché for archaeologists to call things ceremonial when they don’t understand them, but I think in this case that’s really what we have,” says Bubel.

One Ring to Bind Them

By ERIC A. POWELL

Thursday, June 04, 2015

Scientists recently examined a silver ring holding a gem engraved with the word “Allah” that was discovered in a Viking-era woman’s grave by Swedish archaeologists in the late nineteenth century. The team used a scanning electron microscope to determine that the gem, thought to be an amethyst, is actually colored glass, which would have been an exotic material in the Viking world. They also discovered that the ring is still in mint condition, with no sign of wear. “That means it was not an heirloom passed from person to person that randomly ended up in Scandinavia,” says Stockholm University biophysicist Sebastian Wärmländer, who led the team. “The ring was brought here soon after it was made, and corroborates ancient tales about direct contact between Viking Age Scandinavia and the Islamic world.”

Scientists recently examined a silver ring holding a gem engraved with the word “Allah” that was discovered in a Viking-era woman’s grave by Swedish archaeologists in the late nineteenth century. The team used a scanning electron microscope to determine that the gem, thought to be an amethyst, is actually colored glass, which would have been an exotic material in the Viking world. They also discovered that the ring is still in mint condition, with no sign of wear. “That means it was not an heirloom passed from person to person that randomly ended up in Scandinavia,” says Stockholm University biophysicist Sebastian Wärmländer, who led the team. “The ring was brought here soon after it was made, and corroborates ancient tales about direct contact between Viking Age Scandinavia and the Islamic world.”

Cosmic Rays and Australopithecines

By ZACH ZORICH

Thursday, June 04, 2015

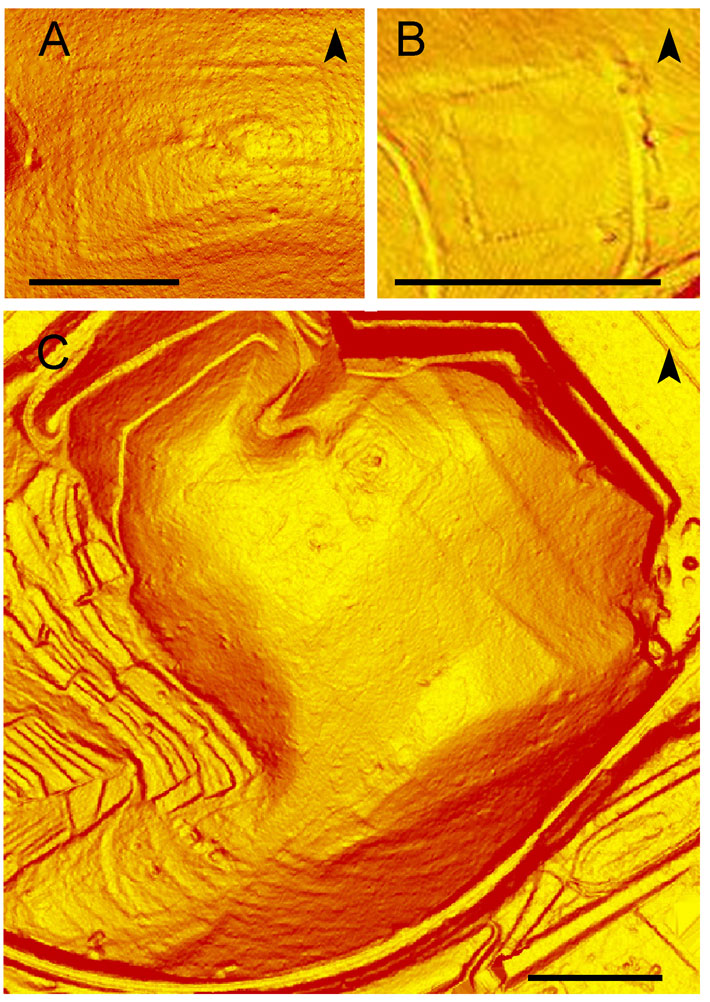

A new dating technique is making it easier for paleoanthropologists to study the human evolutionary record by making it possible to date a wider range of stones and sediments. A team of scientists, including Darryl Granger of Purdue University, has looked to aluminum-26 and beryllium-10, isotopes that are created when rocks are out in the open, exposed to cosmic rays. Once the rocks are buried, the isotopes no longer form, and then begin to decay at known rates. Ultrasensitive instruments that can measure the tiny amounts of these isotopes can tell scientists how long a rock has been underground. Granger used this technique on quartz crystals from South Africa’s Sterkfontein Cave that surrounded the skeletal remains of an early hominin dubbed “Little Foot,” formally known as Australopithecus prometheus. Granger dated the skeleton at 3.67 million years old. The results are controversial because they show that A. prometheus lived at the same time as the human ancestor A. afarensis, which raises questions about the relationship between these species.

A new dating technique is making it easier for paleoanthropologists to study the human evolutionary record by making it possible to date a wider range of stones and sediments. A team of scientists, including Darryl Granger of Purdue University, has looked to aluminum-26 and beryllium-10, isotopes that are created when rocks are out in the open, exposed to cosmic rays. Once the rocks are buried, the isotopes no longer form, and then begin to decay at known rates. Ultrasensitive instruments that can measure the tiny amounts of these isotopes can tell scientists how long a rock has been underground. Granger used this technique on quartz crystals from South Africa’s Sterkfontein Cave that surrounded the skeletal remains of an early hominin dubbed “Little Foot,” formally known as Australopithecus prometheus. Granger dated the skeleton at 3.67 million years old. The results are controversial because they show that A. prometheus lived at the same time as the human ancestor A. afarensis, which raises questions about the relationship between these species.

The Environmental Cost of Empire

By DANIEL WEISS

Thursday, June 04, 2015

Powerful empires throughout history have exploited precious resources, but this extraction can take a toll on the environment. Researchers have recently discovered two examples of imperial mining efforts—separated by hundreds of years and thousands of miles—that left behind pollution that can still be measured today.

Powerful empires throughout history have exploited precious resources, but this extraction can take a toll on the environment. Researchers have recently discovered two examples of imperial mining efforts—separated by hundreds of years and thousands of miles—that left behind pollution that can still be measured today.

When the Mongols conquered China and founded the Yuan Dynasty (A.D. 1271–1368), they established an ambitious silver mining operation near Lake Erhai in Yunnan Province. Production grew rapidly, and by 1328 almost half of the national tax revenue came from silver mined and processed there. Once ore containing silver was mined, it was heated to release impurities such as lead. A recent analysis of sediment cores from Lake Erhai found that lead pollution spiked during the Yuan Dynasty, peaking at three to four times the level caused by modern mining. This surprisingly high level of ancient pollution may be due more to the inefficiency of the refining process than to the amount of silver mined, says Aubrey Hillman, a doctoral candidate in geology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Preindustrial lead pollution due to silver mining has also been found in South America, where the traces show up in a core sample from the Quelccaya Ice Cap, high in the Peruvian Andes. The Incas pioneered silver extraction in the area, but it wasn’t until Spanish colonizers dramatically ramped up production in the sixteenth century that lead was released in quantities large enough to be detected almost five hundred years later by a team led by geoscientist Paolo Gabrielli of The Ohio State University. The Spanish increased the amount of ore mined by using forced Inca labor, and introduced a more efficient refining process in which ore was pulverized, releasing lead-laden dust into the atmosphere. The ore was then mixed with liquid mercury to remove impurities. Taken together, these discoveries provide ample evidence that mineral wealth and pollution have long traveled hand in hand.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

A Spin through Augustan Rome

Off The Grid

The First Toolkit

Anglo-Saxon Jewelry Box

Wrecks of the Pacific Theater

The Environmental Cost of Empire

One Ring to Bind Them

Cosmic Rays and Australopithecines

Bison Bone Mystery

Rome's Earliest Fort

A Parisian Plague

Finding Lost African Homelands

Neanderthal Necklace

Slime Molds and Roman Roads

Open House

World Roundup

Civil War booze, world’s oldest pretzels, Austria’s war camels, coral tombs of the Pacific, and a 2.8-million-year-old human

Artifact

Styling hair in Bronze Age Wales

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement