Features

Cultural Revival

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, August 24, 2015

In recent years, Quinhagak, a small southwestern Alaskan village just inland from the Bering Sea, has, along with other coastal communities in the state, witnessed dramatic erosion due to climate change. The area, located at the southern end of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, has historically been prone to damaging storms and flooding, but now, melting sea ice is resulting in larger waves and has left the shoreline more vulnerable to storm surges. Land once held firm by permafrost has softened and is now easily eaten away by the tides, with the result that anything previously embedded in the permafrost is released.

Around 2007, carved wooden objects started washing up on the beach near Quinhagak, and the source seemed to be a site several miles to the south known to have once been inhabited. The native Yup’ik people who live in the area generally believe in not disturbing their ancestors’ settlements, but they recognized that this was a special case. Artifacts of their past were in danger of being lost forever, and they believed that if these objects could be recovered, younger, culturally adrift members of the community might forge a deeper connection with their heritage. So they called in Rick Knecht, an archaeologist at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, who has extensive experience excavating in Alaska, to examine the threatened site. “We landed there,” Knecht says, “and right away found a complete wooden doll on the beach. We followed the tide line and saw more and more evidence of wooden artifacts. A couple miles down the beach, we could see where they were coming from.” A dark midden partially concealed carved wooden shafts and half of a bentwood bowl. Knecht could tell that large chunks of earth had calved off, and big, grassy clumps could be seen on the beach with artifacts essentially pouring out of them.

The site has been dubbed Nunalleq, which means “Old Village” in the Yup’ik language. Since 2009, Knecht has led an excavation team there for up to six weeks each summer. He now recognizes that Nunalleq was occupied on and off between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, well before the first contact between the Yup’ik people and Russian traders, which took place in the 1830s. The archaeologists have found tens of thousands of artifacts—most made of wood or other organic materials, preserved only because they had been embedded in permafrost—that are providing a rare glimpse of precontact Yup’ik life. Hundreds of wooden dolls, from simple flat sticks to three-dimensional carvings, and a number of wooden masks, some large enough for use in a masked dancing ritual and some small enough that they appear to have been designed for use as playthings with the dolls, have been found. Carvings in wood and ivory of animals important to the Yup’ik people, such as seals and birds, have also been discovered. “On average, a person might find two hundred pieces a day,” says Knecht. “There’s so much information there.” Among the most striking finds has been evidence of a period of fierce internecine conflict that may have gone on for hundreds of years.

New York's Original Seaport

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, September 22, 2015

Over the past 250 years, perhaps no stretch of land in America has undergone greater transformation than Lower Manhattan. Today, its shoreline barely resembles what the earliest Dutch immigrants encountered in the 1600s. The labyrinthine canyons formed by block after block of modern skyscraper construction were once an idyllic setting of small hills, streams, and wetlands. Lower Manhattan is a palimpsest on which each new era has written its own physical history. With the help of archaeology, it is occasionally possible to reconstruct those faintly visible landscapes of the past. The South Street Seaport is located along Lower Manhattan’s eastern shore, near the place where the East River meets the top of New York’s magnificently sheltered harbor. Today it is a tourist-friendly destination with shops, tour boats, and restaurants, and serves as a refuge from the bustle of neighboring Wall Street. No other place epitomizes the growth and transformation of Manhattan in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries more than the South Street Seaport, when it was the busiest port in the United States.

The 11-block area right around the Seaport, nestled in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, has recently been the focus of a city-led initiative to improve its utilities and infrastructure. The city has long hoped to stimulate the neighborhood’s commercial, residential, and touristic appeal, most recently after it was devastated by a seven-foot storm surge during 2012’s Hurricane Sandy. The initiative includes installing new curbs, resurfacing the streets, and maintaining and replacing damaged subterranean utility lines. All of these projects permit and, in fact, require that archaeologists be brought in prior to the work. Alyssa Loorya, founder of Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, is one of the archaeologists contacted by city officials to evaluate sensitive areas slated for construction. Over the past decade her team has excavated areas along Fulton, Front, Beekman, Water, and Pearl Streets, as well as extensive sections of Peck Slip. “We have covered pretty much every block in the historic district that has been excavated since 2005,” she says. “It’s been really nice to get a whole little picture of the way this area developed.”

The 11-block area right around the Seaport, nestled in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, has recently been the focus of a city-led initiative to improve its utilities and infrastructure. The city has long hoped to stimulate the neighborhood’s commercial, residential, and touristic appeal, most recently after it was devastated by a seven-foot storm surge during 2012’s Hurricane Sandy. The initiative includes installing new curbs, resurfacing the streets, and maintaining and replacing damaged subterranean utility lines. All of these projects permit and, in fact, require that archaeologists be brought in prior to the work. Alyssa Loorya, founder of Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, is one of the archaeologists contacted by city officials to evaluate sensitive areas slated for construction. Over the past decade her team has excavated areas along Fulton, Front, Beekman, Water, and Pearl Streets, as well as extensive sections of Peck Slip. “We have covered pretty much every block in the historic district that has been excavated since 2005,” she says. “It’s been really nice to get a whole little picture of the way this area developed.”

Almost none of the land where Loorya’s team has worked existed when the first Europeans arrived in New York Harbor. The original Manhattan shoreline coincides roughly with the line of present-day Pearl Street, three blocks inland. The land associated with Water, Front, and South Streets, which form the backbone of the South Street Seaport, was completely created by human activity. From the late 1600s through the early 1800s, Lower Manhattan’s shoreline gradually crept farther into the East River as part of a deliberate landfilling process. Land, especially waterfront land, has always been at a premium in New York, and it was no different during the city’s early history. The real estate created for the South Street Seaport was extremely valuable, especially to the merchants, ship owners, and shopkeepers responsible for its growth.

|

Article:

|

The Hidden History of New York’s Harbor

|

Golden House of an Emperor

By FEDERICO GURGONE

Monday, August 10, 2015

In no other matter did he act more wasteful than in building a house that stretched from the Palatine to the Esquiline Hill, which he originally named “Transitoria” [House of Passages], but when soon afterwards it was destroyed by fire and rebuilt he called it “Aurea” [Golden House]. A house whose size and elegance these details should be sufficient to relate: Its courtyard was so large that a 120-foot colossal statue of the emperor himself stood there; it was so spacious that it had a mile-long triple portico; also there was a pool of water like a sea, that was surrounded by buildings which gave it the appearance of cities; and besides that, various rural tracts of land with vineyards, cornfields, pastures, and forests, teeming with every kind of animal both wild and domesticated. In other parts of the house, everything was covered in gold and adorned with jewels and mother-of-pearl; dining rooms with fretted ceilings whose ivory panels could be turned so that flowers or perfumes from pipes were sprinkled down from above; the main hall of the dining rooms was round, and it would turn constantly day and night like the Heavens; there were baths, flowing with seawater and with the sulfur springs of the Albula; when he dedicated this house, that had been completed in this manner, he approved of it only so much as to say that he could finally begin to live like a human being. Suetonius, The Lives of the Caesars

In no other matter did he act more wasteful than in building a house that stretched from the Palatine to the Esquiline Hill, which he originally named “Transitoria” [House of Passages], but when soon afterwards it was destroyed by fire and rebuilt he called it “Aurea” [Golden House]. A house whose size and elegance these details should be sufficient to relate: Its courtyard was so large that a 120-foot colossal statue of the emperor himself stood there; it was so spacious that it had a mile-long triple portico; also there was a pool of water like a sea, that was surrounded by buildings which gave it the appearance of cities; and besides that, various rural tracts of land with vineyards, cornfields, pastures, and forests, teeming with every kind of animal both wild and domesticated. In other parts of the house, everything was covered in gold and adorned with jewels and mother-of-pearl; dining rooms with fretted ceilings whose ivory panels could be turned so that flowers or perfumes from pipes were sprinkled down from above; the main hall of the dining rooms was round, and it would turn constantly day and night like the Heavens; there were baths, flowing with seawater and with the sulfur springs of the Albula; when he dedicated this house, that had been completed in this manner, he approved of it only so much as to say that he could finally begin to live like a human being. Suetonius, The Lives of the Caesars

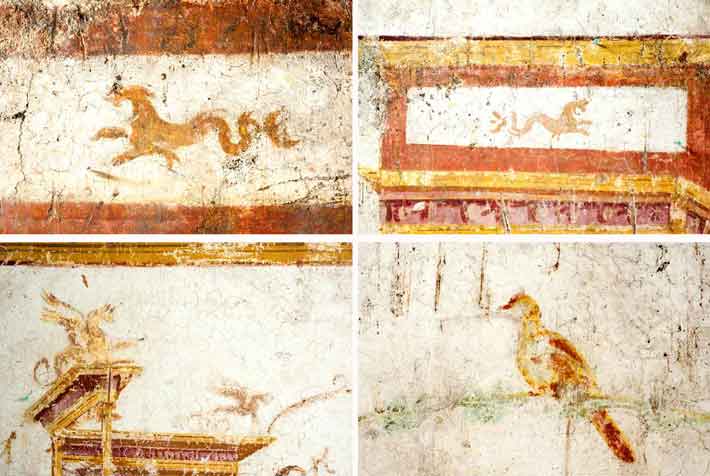

In the mid-first century A.D. there was no building in Rome as sumptuous, ornate, or grand as the Domus Aurea, or “Golden House,” a lavish imperial residence and sprawling park covering hundreds of acres in an area known as the Oppian Hill between the Palatine and Esquiline Hills on the city’s northern side. Constructed by the emperor Nero and born from the ashes of the massive A.D. 64 fire that destroyed the city center and cleared the space that it would occupy—perhaps explaining the persistent suspicion held by many Romans that the emperor himself had set the fire—the vast property had hundreds of rooms. There were walls sheathed in polychrome marble, vaults and ceilings covered in vibrant frescoes by the artist Fabullus, and in precious stones, ivory, and gold, and gardens full of masterpieces of sculpture from Greece and Asia Minor. According to the Roman historian Tacitus, who praises the palace’s architects, Severus and Celer, for having the “ingenuity and courage to try the force of art even against the veto of nature,” what was even more marvelous than the spectacular interiors were “the fields and lakes and the air of solitude given by wooden ground alternating with clear tracts and open landscapes.”

Yet the emperor’s extraordinary palace was never finished, and it stood for only four years—on June 9, A.D. 68, Nero committed suicide after being convinced he was condemned by the Senate to die as a public enemy. His death brought to a close the Julio-Claudian dynasty that had begun with Augustus, and ended a reign distinguished by excessive lasciviousness, cruelty, and violence, and that led to civil war. The next three emperors ruled for only 18 months in total, and all were either murdered or committed suicide. It was not until December of A.D. 69, when Vespasian became emperor, that a period of relative calm that was to last more than a decade began.

Yet the emperor’s extraordinary palace was never finished, and it stood for only four years—on June 9, A.D. 68, Nero committed suicide after being convinced he was condemned by the Senate to die as a public enemy. His death brought to a close the Julio-Claudian dynasty that had begun with Augustus, and ended a reign distinguished by excessive lasciviousness, cruelty, and violence, and that led to civil war. The next three emperors ruled for only 18 months in total, and all were either murdered or committed suicide. It was not until December of A.D. 69, when Vespasian became emperor, that a period of relative calm that was to last more than a decade began.

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Golden House of an Emperor

New York's Original Seaport

Cultural Revival

Letter From England

From the Trenches

Bronze Age Ireland’s Taste in Gold

Off the Grid

A Rare Bird

Atacama’s Decaying Mummies

Bronze Age Traveler

Great Lakes Shipwreck Spotting

Early Parrots in the Southwest

The Red Lady of El Mirón

For the Love of a Noblewoman

Blood on the Ice

Under the Rug

What’s in a Name?

A Place to Hide the Bodies

“T” Marks the Spot

As American as Sliced Bacon in a Can

Surely You Joust?

Artifact

The dragon that guarded Xanadu

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

The site that Knecht and his team are excavating appears, based on carbon dating of organic material, to have been inhabited for some time around 1300 and then steadily from roughly 1450 through 1650. At the end of this period, the archaeologists have discovered, the site was the scene of a terrible massacre in which attackers set a qasgiq on fire with people and dogs still inside. “We found this burned floor with all this burned stuff on it, riddled with arrow points—absolutely riddled,” says Knecht. “We also found the bodies of people who were dragged out of the house, along with the long grass ropes that were used to do so. Their skeletons are burned and kind of dismembered.” Another human skeleton was found inside the house, with an arm outstretched, apparently attempting to dig out from under a sod wall. The displaced skull of a young woman was found with an arrow tip embedded in the back of it. Also discovered inside the house were the remains of a number of dogs that had perished in the fire. “We found this charred beam right across the middle of a dog,” says Knecht, “and it cooked him so fast, so intensely, that he was pretty well preserved.”

The site that Knecht and his team are excavating appears, based on carbon dating of organic material, to have been inhabited for some time around 1300 and then steadily from roughly 1450 through 1650. At the end of this period, the archaeologists have discovered, the site was the scene of a terrible massacre in which attackers set a qasgiq on fire with people and dogs still inside. “We found this burned floor with all this burned stuff on it, riddled with arrow points—absolutely riddled,” says Knecht. “We also found the bodies of people who were dragged out of the house, along with the long grass ropes that were used to do so. Their skeletons are burned and kind of dismembered.” Another human skeleton was found inside the house, with an arm outstretched, apparently attempting to dig out from under a sod wall. The displaced skull of a young woman was found with an arrow tip embedded in the back of it. Also discovered inside the house were the remains of a number of dogs that had perished in the fire. “We found this charred beam right across the middle of a dog,” says Knecht, “and it cooked him so fast, so intensely, that he was pretty well preserved.” The Bow and Arrow Wars came to an end when the Russians arrived in the 1830s, according to Yup’ik oral tradition. The massacre documented by the Nunalleq excavation establishes that warfare was taking place around 1650, nearly 200 years before this encounter, and Fienup-Riordan believes it raged for 300 to 500 years in all. The archaeologists have found evidence that this sustained state of war was so traumatic that it led the residents of Nunalleq to alter the traditional layout of their village. “As the wars heated up,” says Knecht, “they actually took the men’s house and divided it up into apartments so everyone was living in one big building, creating a more fortified setting. It had to be really extreme warfare to actually change your architecture in response to it.”

The Bow and Arrow Wars came to an end when the Russians arrived in the 1830s, according to Yup’ik oral tradition. The massacre documented by the Nunalleq excavation establishes that warfare was taking place around 1650, nearly 200 years before this encounter, and Fienup-Riordan believes it raged for 300 to 500 years in all. The archaeologists have found evidence that this sustained state of war was so traumatic that it led the residents of Nunalleq to alter the traditional layout of their village. “As the wars heated up,” says Knecht, “they actually took the men’s house and divided it up into apartments so everyone was living in one big building, creating a more fortified setting. It had to be really extreme warfare to actually change your architecture in response to it.” The Yup’ik masked dance ritual was called agayuyaraq, which means “way of requesting,” and was traditionally the last of a series of annual winter ceremonies. According to Fienup-Riordan, everyone from a given village, or sometimes multiple villages, would gather in the qasgiq to watch dancers perform with carved wooden masks that frequently depicted animals or part-human, part-animal beings. The dancers were believed to take on the spirits of the animals portrayed by the masks and would make the animals’ sounds as well as entreat them to offer themselves up to hunters in the coming year. Once used, the masks were typically burned, broken, or left out on the tundra to decay. Yup’ik masks were collected by late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century explorers, and their vivid expression of a non-European belief system served as an inspiration to artists such as the Surrealists. Intact masks from the precontact period are extremely rare. However, the archaeologists have found a number of complete masks at the Nunalleq site, the largest of which depicts a creature that is part human and part wolf. These masks may have been undamaged because they had not yet been used in an agayuyaraq when the village was burned to the ground. They may be the oldest complete Yup’ik masks in existence.

The Yup’ik masked dance ritual was called agayuyaraq, which means “way of requesting,” and was traditionally the last of a series of annual winter ceremonies. According to Fienup-Riordan, everyone from a given village, or sometimes multiple villages, would gather in the qasgiq to watch dancers perform with carved wooden masks that frequently depicted animals or part-human, part-animal beings. The dancers were believed to take on the spirits of the animals portrayed by the masks and would make the animals’ sounds as well as entreat them to offer themselves up to hunters in the coming year. Once used, the masks were typically burned, broken, or left out on the tundra to decay. Yup’ik masks were collected by late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century explorers, and their vivid expression of a non-European belief system served as an inspiration to artists such as the Surrealists. Intact masks from the precontact period are extremely rare. However, the archaeologists have found a number of complete masks at the Nunalleq site, the largest of which depicts a creature that is part human and part wolf. These masks may have been undamaged because they had not yet been used in an agayuyaraq when the village was burned to the ground. They may be the oldest complete Yup’ik masks in existence.

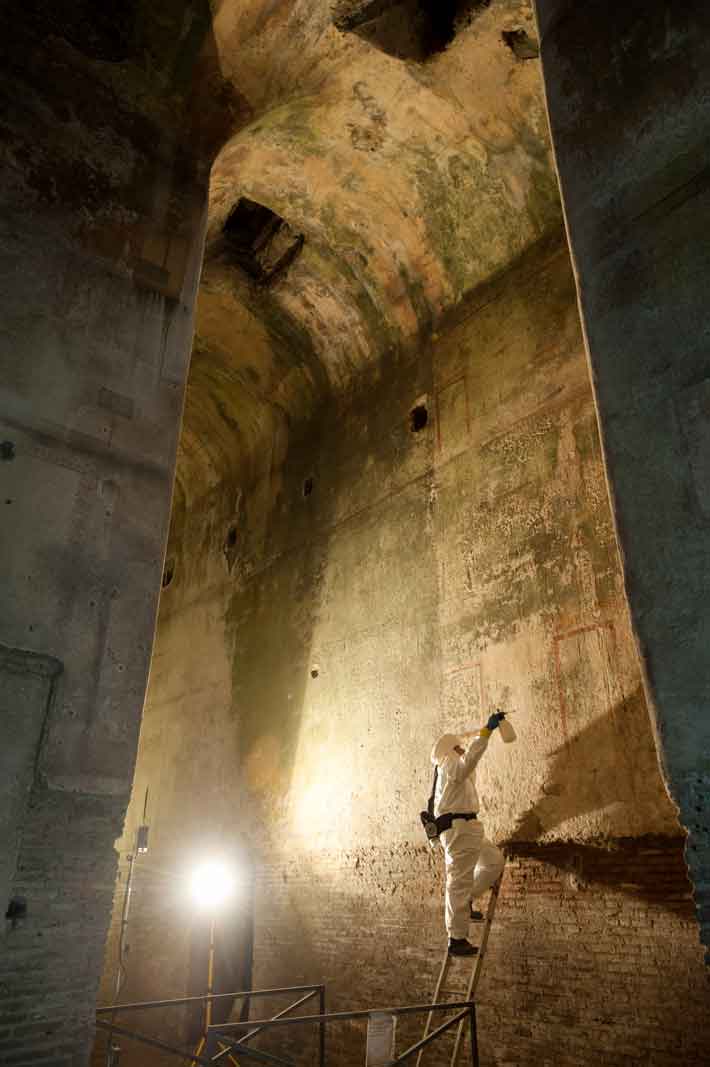

Despite the protection that should have been afforded it by being filled in and covered over so completely, time has not been kind to Nero’s luxurious palace. In the eighteenth century, vineyards covered the Oppian Hill, and in 1871, a large public park incorporating the ruins of the ancient baths was created there. The park was then enlarged during Mussolini’s reign and served as a backdrop for the opening of the newly renovated area around the Colosseum on April 21, 1936—a date that recalls the legendary founding of Rome on the same date in 753 B.C. These decisions were disastrous for the ruins that lay beneath the park. Plant life, including weeds, the roots of ailanthus, acacia, and oak trees, and even a Himalayan pine that, according to very old local residents, was given to Rome by Hirohito, the future emperor of Japan, in 1921, have been infiltrating the cocciopesto (pieces of pottery or brick mixed with lime and sand used as mortar) that holds together the floor of Trajan’s baths and threatens the remains of the Domus Aurea underneath for more than a century. Not only have the plants’ roots, in search of the minerals that abound in ancient mortar, cracked the floor, but chemical compounds released from the roots are also contributing to the cocciopesto’s disintegration.

Despite the protection that should have been afforded it by being filled in and covered over so completely, time has not been kind to Nero’s luxurious palace. In the eighteenth century, vineyards covered the Oppian Hill, and in 1871, a large public park incorporating the ruins of the ancient baths was created there. The park was then enlarged during Mussolini’s reign and served as a backdrop for the opening of the newly renovated area around the Colosseum on April 21, 1936—a date that recalls the legendary founding of Rome on the same date in 753 B.C. These decisions were disastrous for the ruins that lay beneath the park. Plant life, including weeds, the roots of ailanthus, acacia, and oak trees, and even a Himalayan pine that, according to very old local residents, was given to Rome by Hirohito, the future emperor of Japan, in 1921, have been infiltrating the cocciopesto (pieces of pottery or brick mixed with lime and sand used as mortar) that holds together the floor of Trajan’s baths and threatens the remains of the Domus Aurea underneath for more than a century. Not only have the plants’ roots, in search of the minerals that abound in ancient mortar, cracked the floor, but chemical compounds released from the roots are also contributing to the cocciopesto’s disintegration. An ambitious restoration and excavation project led by the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome is now under way. The first priority has been to completely rethink and redesign the park, which is in terrible condition. “Until we have lightened the volume of the park—whose weight increases by up to 30 percent when it rains—by more than half, we are far from any effective solution,” says Fedora Filippi, the archaeologist responsible for the Domus Aurea excavations. “We have had to map and then remove existing trees that are causing the most damage, while documenting the entire excavation phase in detail,” she says. “We can’t just dismantle the garden without taking precautions or we will destroy the palace’s frescoed walls, which have managed to adapt and stay standing over the centuries.” According to landscape architect Gabriella Strano, who, along with agronomist Pier Luigi Cambi and biologist Irene Amici, has worked at the mapping project’s pilot site—the first of 22 planned lots—the weight of the earth covering the archaeological remains is conservatively estimated at 5,500–6,600 pounds per square meter, not including the weight of the trees. One laurel tree, which had stood above the Domus Aurea’s ornate frescoes, was removed and found to have weighed more than 30,000 pounds.

An ambitious restoration and excavation project led by the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome is now under way. The first priority has been to completely rethink and redesign the park, which is in terrible condition. “Until we have lightened the volume of the park—whose weight increases by up to 30 percent when it rains—by more than half, we are far from any effective solution,” says Fedora Filippi, the archaeologist responsible for the Domus Aurea excavations. “We have had to map and then remove existing trees that are causing the most damage, while documenting the entire excavation phase in detail,” she says. “We can’t just dismantle the garden without taking precautions or we will destroy the palace’s frescoed walls, which have managed to adapt and stay standing over the centuries.” According to landscape architect Gabriella Strano, who, along with agronomist Pier Luigi Cambi and biologist Irene Amici, has worked at the mapping project’s pilot site—the first of 22 planned lots—the weight of the earth covering the archaeological remains is conservatively estimated at 5,500–6,600 pounds per square meter, not including the weight of the trees. One laurel tree, which had stood above the Domus Aurea’s ornate frescoes, was removed and found to have weighed more than 30,000 pounds.