Features

Where There's Smoke...

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, October 27, 2015

One morning in 2008, while waiting for a light to change at the corner of Wilshire and Sepulveda Boulevards in Los Angeles, archaeologist Anthony Graesch jumped out of his pickup truck. In the 75 seconds between green lights, much to the mystification of his fellow commuters, he swept all the garbage—primarily hundreds of cigarette butts—that had accumulated against the curb of the median into a 10-gallon trash bag. Graesch tossed it into the truck bed, hopped back in the cab, and continued to his office at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he was a postdoctoral researcher in anthropology and archaeology.

Like many archaeologists, Graesch says, he looks down a lot, reflexively observing the bits of urban flotsam around him, and he had developed a minor obsession with cigarette butts. “I couldn’t stop seeing them,” he says. A few years later, when he took a full-time position at Connecticut College in New London, where he is now chair of the anthropology department, this interest and that bag of L.A. curbside trash went cross-country with him.

Garbage has long been a critical part of the human material record to archaeologists, middens, privies, and trash heaps are consistent sources of knowledge, full of bones, potsherds, broken tools, pipestems, and more, across the world and throughout human history. “It’s pretty much the bread and butter of archaeological research,” says Graesch—so much so that when archaeologists began to look at the contemporary world, garbage was a natural target. In the 1970s, William Rathje, a legendary archaeologist at the University of Arizona, pioneered the field of garbology, or the study of modern waste using archaeological methods. There have been many other examinations of modern artifacts, but decades later Rathje’s work remains the most cited example of archaeology of the contemporary—how modern material culture reflects behavior and society.

Garbage has long been a critical part of the human material record to archaeologists, middens, privies, and trash heaps are consistent sources of knowledge, full of bones, potsherds, broken tools, pipestems, and more, across the world and throughout human history. “It’s pretty much the bread and butter of archaeological research,” says Graesch—so much so that when archaeologists began to look at the contemporary world, garbage was a natural target. In the 1970s, William Rathje, a legendary archaeologist at the University of Arizona, pioneered the field of garbology, or the study of modern waste using archaeological methods. There have been many other examinations of modern artifacts, but decades later Rathje’s work remains the most cited example of archaeology of the contemporary—how modern material culture reflects behavior and society.

Graesch’s impulse to collect trash, which grew from the work of Rathje and others, has again brought the archaeological eye to modern rubbish and is providing a useful approach for teaching theory and methods to his undergraduate students. Among the challenges of teaching archaeology, Graesch explains, is demonstrating why archaeology matters. Modern artifacts, he has found, can help illustrate how behavior relates to community and how modern questions and problems appear, and can be studied, in the material record.

The Acropolis of Athens

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Wednesday, October 07, 2015

It’s much easier to build a new building,” says Vassiliki Eleftheriou, “than to rebuild an ancient one.” Eleftheriou, an architect by training, is director of the Acropolis Restoration Service, where she oversees what could be considered the most daunting project in the history of archaeological conservation.

For thousands of years the monuments of the Athenian Acropolis have been regarded not only as examples of extraordinary skill and beauty, but also as potent symbols of religious devotion and civic and national identity. “Although there were many important sanctuaries and public spaces in Athens and across Attica,” says classical art historian Jeffrey Hurwit of the University of Oregon, “the Acropolis stands as what might be called the central repository of Athenians’ conceptions of themselves. These monuments and sculptures presented images of the gods and goddesses—Athena herself above all—and also of the Athenians and their heroes.” The intention, says Hurwit, was to represent Athens as the greatest of Greek cities and the Athenians as the greatest of Greeks. “To walk through the classical Acropolis was to traverse a marble paean to Athens itself,” he says.

The Acropolis rises nearly 500 feet above the Ilissos Valley, measures about 360 feet north to south and 820 feet east to west, and has a surface area of about seven and a half acres. The site was leveled with artificial fill, in places as much as 55 feet thick, to create a surface upon which to build. Atop it sit the four major standing structures dating to the city’s massive building program of the fifth century B.C., initiated after the destruction of earlier monuments in 480 B.C. by the Persians: the Propylaia, Temple of Athena Nike, Erechtheion, and Parthenon. Over the millennia the deterioration of these monuments as a result of the passage of time, and the damage to them from myriad other causes including wars, improper or overly intrusive excavations, new construction, earthquakes, previous restoration efforts, the vast number of visitors to the site, and, most recently, the ravages of pollution and acid rain, have been almost incalculable. In 1975, the Greek government began a large-scale, multidisciplinary project to address the declining condition of these structures, as well as of a lesser-known building called the Arrephorion, the defensive walls encircling the Acropolis, and the so-called “scattered members,” the thousands of complete, nearly complete, and fragmentary pieces of stone and marble that lie all over the surface of the Acropolis.

What began as a project to rescue the monuments from further decay and instability has evolved into a comprehensive effort not only to restore them, but also to re-create their original appearance insofar as possible. When faced with this exceptional task, the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments followed a governing principle that is applied to all their work. Since the project’s inception, teams working on the Acropolis have employed anastylosis, an intervention technique dating to the beginning of the nineteenth century whereby a structure is rebuilt using original materials. New materials are employed only when necessary, must be easily distinguishable from the old, and must be replaceable should better materials or technologies be found. According to Eleftheriou, this has always been one of the greatest challenges. “It’s important to use as much ancient material as we can, but there is a limit to how much we can actually use,” she says. This is especially true when the team confronts previous efforts at anastylosis. “When we work on sections that have been restored before, it’s difficult not to use new materials because previous restorers often put ancient materials in the wrong places and damaged them. So we try to use compatible materials in a compatible way,” she explains.

The most ubiquitous and catastrophic of these previous efforts were those of the engineer Nikolaos Balanos, who, between 1898 and 1940, supervised an early attempt to restore the Acropolis. Although the techniques he employed, primarily the use of Portland cement mortar, steel reinforcements, and iron clamps, were generally accepted at the time, after only a short while, the materials started to deteriorate and rust, damaging and often cracking the ancient stone.

After four decades of intensive work by hundreds of experts in archaeology, architecture, marble working, masonry, restoration, conservation, and mechanical, chemical, and structural engineering, much has been accomplished. Already the restoration of two of the major buildings, the Erechtheion and the Temple of Athena Nike, has been completed, as has much of the work on the Propylaia and on large sections of the Parthenon. In the process, the team has acquired new information about these emblematic buildings. “The Acropolis restoration project has added immeasurably to our knowledge of the fifth-century B.C. monuments atop the Acropolis. Not only has it recovered, identified, and repositioned many once-scattered blocks,” says Hurwit, “it has also revealed new features, such as evidence for previously unsuspected windows on the east wall of the Parthenon.”

Despite the magnitude of the tasks that remain, Eleftheriou takes both heart and inspiration from the work that she and the team of more than 150 do every day, and also from the ancient artisans who created the Acropolis’ monuments. “What I have learned,” she says, “is that the ancient architects and engineers faced the same challenges we still do.”

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Second Americans?

Off the Grid

How Much Water Reached Rome?

Paleo-Dentistry

Friars' Leather Shop

The Gates of Gath

Slinky Nordic Treasures

Lake George's Unfinished Fort

Last Flight of a Tuskegee Airman

Mysterious Golden Sacrifice

Aftermath of War

Game of Diplomacy

The Magnetism of the Iron Age

Rituals of Maya Kingship

Premature Aging

Switzerland Everlasting

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

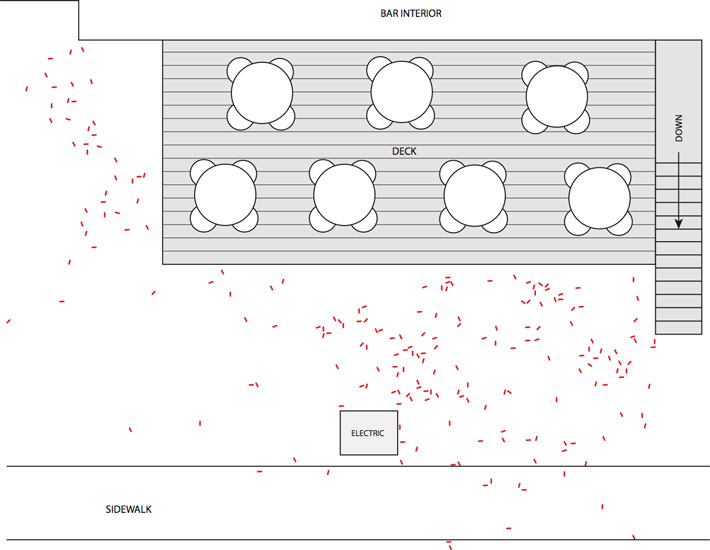

It’s little surprise that Graesch saw cigarette butts everywhere upon his arrival in Connecticut. He observed that they were clustered around the town’s high concentration of bars, each with its own style: sports bars, biker bars, rock ’n’ roll bars, gay bars, an Irish pub, and others. This got him thinking about drinking establishments and how a small city such as New London could support so many. They are places where people congregate primarily for social purposes—a role historically served by town squares, markets, or churches. “Identity,” Graesch says, “is at the root of all archaeological research, even if it isn’t explicitly recognized as such. We aim to understand the behaviors—social, economic, political, religious—that bring together and divide groups of humans.” In these social spaces people form shared identities, identities that might be visible in their material culture.

It’s little surprise that Graesch saw cigarette butts everywhere upon his arrival in Connecticut. He observed that they were clustered around the town’s high concentration of bars, each with its own style: sports bars, biker bars, rock ’n’ roll bars, gay bars, an Irish pub, and others. This got him thinking about drinking establishments and how a small city such as New London could support so many. They are places where people congregate primarily for social purposes—a role historically served by town squares, markets, or churches. “Identity,” Graesch says, “is at the root of all archaeological research, even if it isn’t explicitly recognized as such. We aim to understand the behaviors—social, economic, political, religious—that bring together and divide groups of humans.” In these social spaces people form shared identities, identities that might be visible in their material culture.

The contents of each sample bag were placed in a plastic tray and then the butts were allotted to petri dishes based on type and provenience. “We sorted through our collection bags like we were digging for gold,” says Zoë Leib, a student in the 2013 class. “Really stinky, damp gold.” The students documented the presence of lipstick or gloss, weathering, how much unsmoked paper remained, and the method of extinguishing (the twist, the crush, the twist and crush, and the “I’m so angry I’m going to squish it into a tiny ball”—terms of art, all). Each of these attributes may reflect, together or in isolation, some aspect of the social ritual of smoking and bar-centric community building.

The contents of each sample bag were placed in a plastic tray and then the butts were allotted to petri dishes based on type and provenience. “We sorted through our collection bags like we were digging for gold,” says Zoë Leib, a student in the 2013 class. “Really stinky, damp gold.” The students documented the presence of lipstick or gloss, weathering, how much unsmoked paper remained, and the method of extinguishing (the twist, the crush, the twist and crush, and the “I’m so angry I’m going to squish it into a tiny ball”—terms of art, all). Each of these attributes may reflect, together or in isolation, some aspect of the social ritual of smoking and bar-centric community building.