Acropolis

Circuit Walls

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Wednesday, October 07, 2015

Although people had been living on the Acropolis since the Neolithic period (ca. 4000–3200 B.C.), it was not until the Bronze Age (ca. 3200–1100 B.C.) that the rock became a fortified citadel with a palace. The first defensive wall atop the Acropolis was built in the thirteenth century B.C. by the Mycenaeans, a civilization that thrived in Greece between about 1600 and 1100 B.C. Long after the Mycenaeans were gone, their wall survived—and some sections still do—until it was severely damaged by the Persians in 480 B.C., after which a new 2,500-foot circuit wall was built as part of the fifth-century B.C. building program. In some places, pieces of monuments destroyed earlier in the century were used.

Although people had been living on the Acropolis since the Neolithic period (ca. 4000–3200 B.C.), it was not until the Bronze Age (ca. 3200–1100 B.C.) that the rock became a fortified citadel with a palace. The first defensive wall atop the Acropolis was built in the thirteenth century B.C. by the Mycenaeans, a civilization that thrived in Greece between about 1600 and 1100 B.C. Long after the Mycenaeans were gone, their wall survived—and some sections still do—until it was severely damaged by the Persians in 480 B.C., after which a new 2,500-foot circuit wall was built as part of the fifth-century B.C. building program. In some places, pieces of monuments destroyed earlier in the century were used.

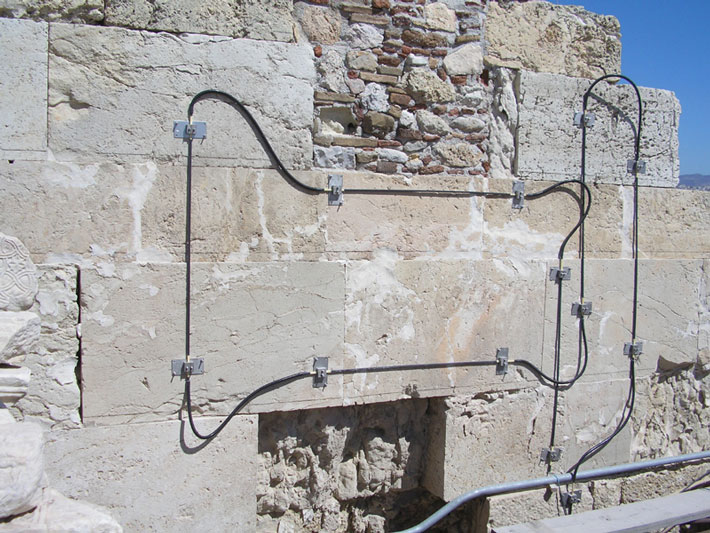

For more than three decades the circuit walls have been exhaustively documented, constantly maintained, and actively monitored using traditional methods, such as inspecting cracks and removing roots and plants, in combination with the latest and most accurate technology available. A complete photogrammetric survey and 3-D scan of the walls has been completed, optical fibers have been installed to measure strain, and a highly precise nickel-iron alloy underground wire has been placed between the Parthenon and the south wall to measure micromovements.

For more than three decades the circuit walls have been exhaustively documented, constantly maintained, and actively monitored using traditional methods, such as inspecting cracks and removing roots and plants, in combination with the latest and most accurate technology available. A complete photogrammetric survey and 3-D scan of the walls has been completed, optical fibers have been installed to measure strain, and a highly precise nickel-iron alloy underground wire has been placed between the Parthenon and the south wall to measure micromovements.

As part of the conservation of the walls, the limestone and schist of the Acropolis itself was also consolidated. Between 1979 and 1993, unstable rocks were anchored to the main mass of the Acropolis in 22 places with stainless steel rods, and gaps and fissures in the rock were sealed with injections of cement.

Propylaia

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Wednesday, October 07, 2015

Ever since the mid-sixth century B.C., a monumental gateway has stood on the west side of the Acropolis at the entrance to Athena’s sanctuary. The original gate was replaced by one that was subsequently destroyed by the Persians and then repaired. The impressive structure seen today—actually three buildings on two different levels—was built between 437 and 432 B.C. by the architect Mnesikles. Many sections of the gate restored by Nikolaos Balanos in the early twentieth century have been dismantled, repaired, and replaced, with much of the recent work focused on the Propylaia’s once brightly painted marble coffered ceilings. Now completed, this project required arresting the deterioration of the marble resulting from the iron reinforcements used by Balanos. In addition, 24,00 architectural members needed to be properly identified—including ones that hadn’t been used in earlier restorations, fragments wrongly placed, and pieces that required their own restoration—in order to determine what needed to be fashioned anew. As with the other buildings of the Acropolis, the Propylaia was repeatedly used for purposes different from those originally intended—it has been a church, a residence for Frankish dukes, and a garrison and munitions store under the Turks. The most recent effort has succeeded in restoring the fifth-century B.C. experience of entering the Acropolis through an impressively roofed structure, as Mnesikles intended.

Ever since the mid-sixth century B.C., a monumental gateway has stood on the west side of the Acropolis at the entrance to Athena’s sanctuary. The original gate was replaced by one that was subsequently destroyed by the Persians and then repaired. The impressive structure seen today—actually three buildings on two different levels—was built between 437 and 432 B.C. by the architect Mnesikles. Many sections of the gate restored by Nikolaos Balanos in the early twentieth century have been dismantled, repaired, and replaced, with much of the recent work focused on the Propylaia’s once brightly painted marble coffered ceilings. Now completed, this project required arresting the deterioration of the marble resulting from the iron reinforcements used by Balanos. In addition, 24,00 architectural members needed to be properly identified—including ones that hadn’t been used in earlier restorations, fragments wrongly placed, and pieces that required their own restoration—in order to determine what needed to be fashioned anew. As with the other buildings of the Acropolis, the Propylaia was repeatedly used for purposes different from those originally intended—it has been a church, a residence for Frankish dukes, and a garrison and munitions store under the Turks. The most recent effort has succeeded in restoring the fifth-century B.C. experience of entering the Acropolis through an impressively roofed structure, as Mnesikles intended.

Erechtheion

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Wednesday, October 07, 2015

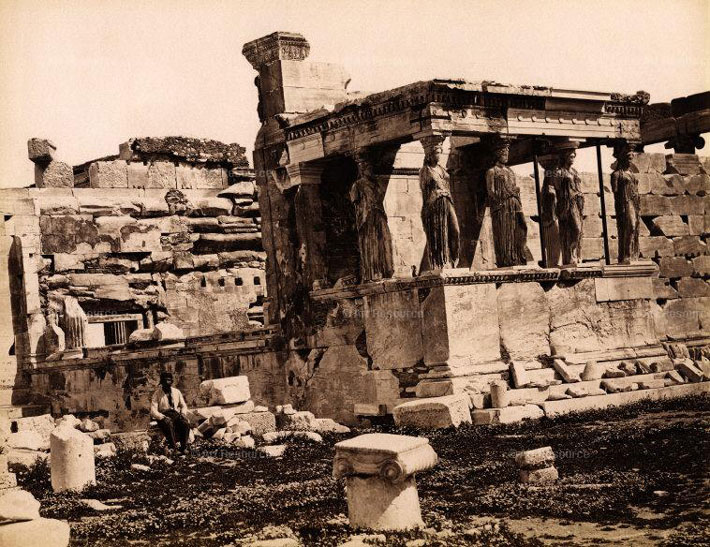

In many ways, the story of the Erechtheion is the story of Athens. “The Erechtheion was a means to encompass, within its footprint, relics of early Athenian myth and religion,” says classical art historian Jeffrey Hurwit. It was there that the memory of the dispute between Athena and Poseidon over the patronage of the city was preserved in what the Athenians regarded as the impression of the god’s trident, visible through a hole left in the floor of the north porch. That foundational legend was also preserved in the tales of a sea he caused to well up during the contest, long believed to be under the building, and in the olive tree that Athena caused to sprout on this spot and that marked her victory. And in this location was kept the olivewood statue of Athena Polias (Athena of the City), the Athenians’ most sacred relic, an object so ancient that not even they knew where it had come from.

Since its construction on the Acropolis’ north side between 421 and 406 B.C., when it replaced an earlier temple to Athena, the Erechtheion—named after Erechtheus, king of Athens and foster son of Athena—has had a complicated history of use, reuse, destruction, and renovation that mirrors the history of the city. In the fifth century B.C., the unique, asymmetrical structure—its highly unusual shape largely determined by the irregular terrain—served not only as a temple to both Athena and Poseidon, but also as home to the cults of the god Hephaistos, Erechtheus, and the hero Boutes, Erechtheus’ brother. The building underwent its first major repairs after it was burned during the Roman general Sulla’s siege of Athens in the first century B.C. Since then the Erechtheion has been a church (in the early Byzantine period), a palace for the bishop (during the Frankish period), and a dwelling for the harem of the Turkish garrison commander (in the Ottoman period). Between 1801 and 1812, sculptures, including one of the six caryatids that held up the south porch, were removed to England by Lord Elgin, and during the Greek War of Independence, the ceiling of the north porch was blown up.

Since its construction on the Acropolis’ north side between 421 and 406 B.C., when it replaced an earlier temple to Athena, the Erechtheion—named after Erechtheus, king of Athens and foster son of Athena—has had a complicated history of use, reuse, destruction, and renovation that mirrors the history of the city. In the fifth century B.C., the unique, asymmetrical structure—its highly unusual shape largely determined by the irregular terrain—served not only as a temple to both Athena and Poseidon, but also as home to the cults of the god Hephaistos, Erechtheus, and the hero Boutes, Erechtheus’ brother. The building underwent its first major repairs after it was burned during the Roman general Sulla’s siege of Athens in the first century B.C. Since then the Erechtheion has been a church (in the early Byzantine period), a palace for the bishop (during the Frankish period), and a dwelling for the harem of the Turkish garrison commander (in the Ottoman period). Between 1801 and 1812, sculptures, including one of the six caryatids that held up the south porch, were removed to England by Lord Elgin, and during the Greek War of Independence, the ceiling of the north porch was blown up.

The Erechtheion was the first building that Nikolaos Balanos addressed during his Acropolis restoration project, and thus the first place where he employed the techniques that were to prove so disastrous—the use of corrosive iron to reinforce fragile architectural members, the cutting and removal of ancient stones, and the haphazard placement of random fragments to fill in and restore missing sections of the ancient buildings. As a result of Balanos’ interventions and the building’s repeated recasting, much about its ancient appearance is lost. But between 1979 and 1987, 23 blocks of the north wall that had been incorrectly used to restore the south wall were replaced in their original positions, and new blocks were made for the south wall. This raised the height of the north wall by four courses, bringing it closer to its original height. Because scholars haven’t yet discovered a way to protect the surface of the marble that makes up the Acropolis’ major monuments, the remaining caryatids that supported the south porch were removed in 1978 and all were replaced with copies. The originals now sit in the Acropolis Museum, where they were recently cleaned using pulse laser ablation, the same technique that was used on the coffered ceiling of the caryatid porch and on the west frieze of the Parthenon. This technique, explains Demetrios Anglos of the Foundation for Research and Technology at the Institute of Electronic Structure and Laser in Crete, who oversaw the efforts, involves directing the laser for a short time in a highly focused way and concentrating it on a small volume of material so the dirt is removed in a nondestructive manner. “We do this to clean the marble,” Anglos explains, “and to reach a place that is acceptable from both a materials and aesthetic point of view.”

Temple of Athena Nike

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Wednesday, October 07, 2015

The small marble temple on the rock’s southwest corner dedicated to Athena Nike (Victorious Athena), built between 427 and 424 B.C., was the first building on the Acropolis to be restored. In the seventeenth century, the temple was demolished and its stones used to strengthen the Turkish fortification wall. From 1836 to 1845, it was re-erected in the first of three attempts at anastylosis. Between 1935 and 1940, as part of Nikolaos Balanos’ restoration work, the temple was again dismantled and put back together, and finally, between 2000 and 2010, the most recent restoration was completed. This last required demolition and replacement of the concrete slab installed by Balanos, upon which the temple sat, with a stainless steel grid, as well as the complete dismantling, restoration, and resetting of all its architectural members. During this process, pieces of column drums and capitals, parts of the coffered ceiling, and blocks of the frieze, cornices, and the pediment were all put back where they had originally been. “We had the opportunity to correct mistakes in the positions of stones from the walls and columns. Balanos had put the best-looking ones in the front, even though some of them had originally been on the back,” says architect Vassiliki Eleftheriou. In addition, some fragments that had never been used in previous restorations were identified and set on the building.

The restored temple seen today is not the only monument in this location. As part of the current project, scholars have also conserved an earlier limestone temple to Athena, probably dating to the sixth century B.C., that was discovered in 1936 and that lies beneath the later temple. This earlier structure, along with the base of the cult statue of the goddess also found in 1936, and a tower dating to the Mycenaean period, have been restored and are visible in the basement of the classical structure. Work is currently under way to make this ancient sanctuary accessible to the public.

The restored temple seen today is not the only monument in this location. As part of the current project, scholars have also conserved an earlier limestone temple to Athena, probably dating to the sixth century B.C., that was discovered in 1936 and that lies beneath the later temple. This earlier structure, along with the base of the cult statue of the goddess also found in 1936, and a tower dating to the Mycenaean period, have been restored and are visible in the basement of the classical structure. Work is currently under way to make this ancient sanctuary accessible to the public.

Arrephorion

Wednesday, October 07, 2015

Against the Acropolis’ north fortification wall sits a small, square building that Wilhelm Dörpfeld identified in the 1920s as the Arrephorion. (Dörpfeld was the German archaeologist and architect who pioneered the techniques of stratigraphic archaeology and was Heinrich Schliemann’s successor at Troy.) The Arrephorion was the home of the Arrephoroi, two aristocratic girls between the ages of 7 and 11, who were chosen each year to serve in the cult of the goddess Athena. During the festival of the Arrephoria, celebrated at night in mid-summer, the girls enacted a secret ritual in which they carried chests above their heads—the contents were and still remain a mystery—and descended the Acropolis, likely by means of a stairway concealed inside the north wall.

While it is known that the Arrephorion, constructed in the fifth century B.C., once had a square hall and four-column colonnade, as well as a rectangular courtyard, all that survive are limestone foundation blocks and fragments of marble. Because the limestone is fragile and the marble cannot be used to restore any extant structure, it was decided that, in contrast to the plans for any other monument on the Acropolis, the Arrephorion would be reburied to protect it. The structure was backfilled in 2006 with soil that could easily be removed if necessary, but is also intended to remain in place for at least 120 years with minimal changes resulting from moisture, seismic activity, or pressure applied to it by contact with the circuit walls.

While it is known that the Arrephorion, constructed in the fifth century B.C., once had a square hall and four-column colonnade, as well as a rectangular courtyard, all that survive are limestone foundation blocks and fragments of marble. Because the limestone is fragile and the marble cannot be used to restore any extant structure, it was decided that, in contrast to the plans for any other monument on the Acropolis, the Arrephorion would be reburied to protect it. The structure was backfilled in 2006 with soil that could easily be removed if necessary, but is also intended to remain in place for at least 120 years with minimal changes resulting from moisture, seismic activity, or pressure applied to it by contact with the circuit walls.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement