From the Trenches

The Gates of Gath

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, October 05, 2015

In the tenth and ninth centuries B.C., and probably even earlier, Gath was likely the largest city in Philistia, a pentapolis—five-city confederation—in the southern Levant. A team of archaeologists led by Aren Maeir of Bar-Ilan University has just uncovered one source of Gath’s strength—the monumental stone gate and a section of the wall that served as both entrance to and protection for the city. As home to the Philistines, including, according to the Old Testament, the giant warrior Goliath, Gath was the strongest and most dominant city in the region for nearly two centuries. Along with Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gaza, it was also a formidable foe of the early Judahite kingdom (also called the “United Kingdom” of David and Solomon) and, says Maeir, “played a central role in the geopolitical scene during these periods.”

Friars' Leather Shop

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, October 05, 2015

An excavation in Oxford, England, conducted by Oxford Archaeology in advance of the expansion of a shopping center, has turned up a large number of leather and wood objects dating to the fourteenth century, when the site was occupied by buildings associated with the Greyfriars religious order. The artifacts were unusually well preserved because they were buried beneath the water table. Among the finds are around 100 leather shoes, a leather bag, a leather money purse, and a wooden bowl. “Somebody seems to have been saving up worn-out shoes,” says Ben Ford, the excavation’s project manager. “Maybe it was a cobbler working at the friary.”

How Much Water Reached Rome?

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, October 05, 2015

Rome’s 11 aqueducts, some extending for more than 50 miles, transported enough water to feed the city’s 591 public fountains, as well as countless private residences. However, experts have long been divided about how much water each aqueduct could actually convey. “Many assumptions have been made based on some pretty unreliable ancient data concerning the size of the flows of Rome’s aqueducts, giving some very inflated figures,” says archaeologist Duncan Keenan-Jones of the University of Glasgow. “We thought it was important to adopt a more scientific approach.”

Rome’s 11 aqueducts, some extending for more than 50 miles, transported enough water to feed the city’s 591 public fountains, as well as countless private residences. However, experts have long been divided about how much water each aqueduct could actually convey. “Many assumptions have been made based on some pretty unreliable ancient data concerning the size of the flows of Rome’s aqueducts, giving some very inflated figures,” says archaeologist Duncan Keenan-Jones of the University of Glasgow. “We thought it was important to adopt a more scientific approach.”

Keenan-Jones is part of a team of scientists who measured the amount of residual mineral deposits in the Anio Novus aqueduct to accurately gauge the depth and flow rate of water. By analyzing travertine—a type of limestone deposit—that was left on the aqueduct’s interior walls and floor, the researchers calculated a flow rate of 1.4 cubic meters per second, or between 100,000 and 150,000 cubic meters (25 to 40 million gallons) per day, a number below traditional estimates. The amount of water actually reaching the city was hindered by the buildup of travertine on the aqueduct’s interior, which considerably lessened the flow. “Our work has shown that often, even shortly after the aqueducts were built, the flow rates were well below the capacity estimates,” says Keenan-Jones. “Ancient Rome had a lot of water, but not nearly as much as has often been claimed.”

Paleo-Dentistry

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, October 05, 2015

A team led by Stefano Benazzi of the University of Bologna has discovered the earliest known evidence of dental work in a 14,000-year-old molar from a male skeleton found in northern Italy in 1988. Examination of the tooth with a scanning electron microscope revealed striations consistent with scratching and chipping with a sharp stone tool, apparently to remove decayed material. Enamel in the area of the cavity is worn away, suggesting the treatment occurred long before death. Benazzi believes that the likely very painful practice of removing tooth decay probably evolved from the use of wooden and bone toothpicks, many of which have been found at Paleolithic sites.

A team led by Stefano Benazzi of the University of Bologna has discovered the earliest known evidence of dental work in a 14,000-year-old molar from a male skeleton found in northern Italy in 1988. Examination of the tooth with a scanning electron microscope revealed striations consistent with scratching and chipping with a sharp stone tool, apparently to remove decayed material. Enamel in the area of the cavity is worn away, suggesting the treatment occurred long before death. Benazzi believes that the likely very painful practice of removing tooth decay probably evolved from the use of wooden and bone toothpicks, many of which have been found at Paleolithic sites.

Off the Grid

By MALIN GRUNBERG BANYASZ

Monday, October 05, 2015

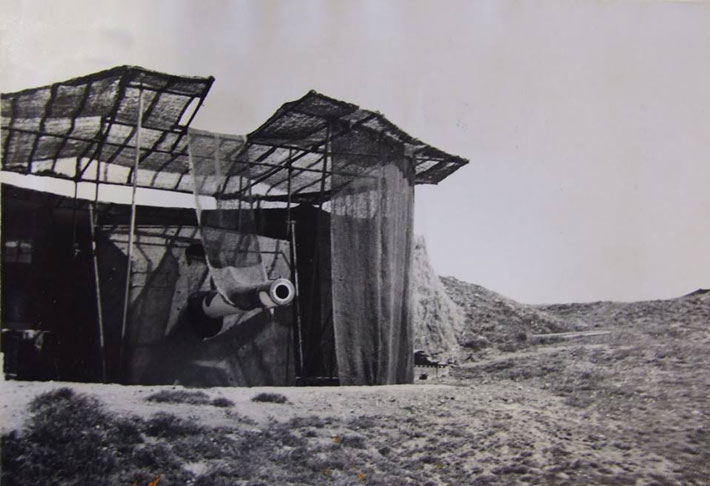

In 1940, newly installed British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the construction of gun batteries and tunnels in the chalk of the White Cliffs of Dover, just 21 miles from Nazi-occupied France, to prevent German ships from moving freely through the English Channel. The Fan Bay Deep Shelter, a series of tunnels to protect the gun battery teams from bombardment, was completed in just 100 days and could house up to 185 soldiers.

In 1940, newly installed British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the construction of gun batteries and tunnels in the chalk of the White Cliffs of Dover, just 21 miles from Nazi-occupied France, to prevent German ships from moving freely through the English Channel. The Fan Bay Deep Shelter, a series of tunnels to protect the gun battery teams from bombardment, was completed in just 100 days and could house up to 185 soldiers.

The tunnels were taken out of commission in the 1950s and filled with rubble in the 1970s. The National Trust purchased the land in 2012, and the next year the shelter was rediscovered. The volunteer staff of the Fan Bay Project, alongside archaeologists, mine consultants, engineers, and geologists, moved 100 tons of debris by hand over 18 months, revealing the tunnels’ infrastructure and a wealth of graffiti from the time. Jon Barker of the National Trust and Keith Parfitt of the Canterbury Archaeological Trust say that the tunnels are time capsules of emotion and provide great insight into wartime life.

The site

The site

The Fan Bay installation consisted of a gun battery, searchlights, a generator house, barracks, magazines, and a plotting room, all situated above the Deep Shelter—five bomb-proof tunnels and a hospital totaling 3,500 square feet, sitting 75 feet below the top of the cliffs. The clearing of the tunnels has made them accessible to the general public for the first time. Reinforced with girders and metal sheeting, they preserve an abundance of wartime graffiti, including soldiers’ names and service numbers. Near a toilet are rhymes about one challenge of wartime: the lack of toilet paper. “If you come into this hall use the paper not this wall,” one reads. “If no paper can be found then run your arse along the ground.” Guides lead visitors—with hard hats and flashlights—down 125 steps to the tunnels, as well as to two World War I sound mirrors, large concave concrete discs that were among the first early warning air defense devices in Britain.

While you’re there

The White Cliffs of Dover live up to their name, and a variety of viewpoints offer sweeping vistas—Stay away from the cliff edge!—of the chalk facade, the channel, and, on a clear day, France. An engineering marvel of the Victorian period, the South Foreland Lighthouse just outside Dover was the first in the world to use electric light, and still serves traditional tea in the lighthouse-keeper’s cottage. In addition, there are Roman lighthouses in Dover, overlooking the site of Portus Dubris, a second-century port, which includes the Roman Painted House, a mansio, or government hostel, decorated with more than 400 square feet of murals related to Bacchus, the god of wine.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Second Americans?

Off the Grid

How Much Water Reached Rome?

Paleo-Dentistry

Friars' Leather Shop

The Gates of Gath

Slinky Nordic Treasures

Lake George's Unfinished Fort

Last Flight of a Tuskegee Airman

Mysterious Golden Sacrifice

Aftermath of War

Game of Diplomacy

The Magnetism of the Iron Age

Rituals of Maya Kingship

Premature Aging

Switzerland Everlasting

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement