Top 10

Baby Bobcat

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, December 07, 2015

The native cultures of ancient North America expressed their close relationship to animals in their art and their rituals, none more so than the Hopewell Culture, which flourished along the rivers of the Northeast and Midwest between 200 B.C. and A.D. 500. When Angela Perri of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology opened a box in the Illinois State Museum’s collection labeled “puppy,” she expected to find the remains of a dog burial, common enough in the Hopewell Culture. The bones had come from a 1980s rescue excavation at the Elizabeth Mounds site in western Illinois. “As soon as I opened it, I said, ‘I think we have a problem,’” Perri recalls. “I knew right away from its distinctive teeth that it was a cat.”

The native cultures of ancient North America expressed their close relationship to animals in their art and their rituals, none more so than the Hopewell Culture, which flourished along the rivers of the Northeast and Midwest between 200 B.C. and A.D. 500. When Angela Perri of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology opened a box in the Illinois State Museum’s collection labeled “puppy,” she expected to find the remains of a dog burial, common enough in the Hopewell Culture. The bones had come from a 1980s rescue excavation at the Elizabeth Mounds site in western Illinois. “As soon as I opened it, I said, ‘I think we have a problem,’” Perri recalls. “I knew right away from its distinctive teeth that it was a cat.”

She determined that the nearly complete skeleton belonged to a juvenile bobcat, between four and seven months old. The bones show no signs of trauma, indicating the bobkitten likely died of natural causes, probably malnutrition. “It looks like they came across a baby that they tried to raise but failed,” says Perri. “When it died they had become close enough to it that it warranted this special burial.”

Along with the bones, Perri found four shell beads and two carved effigies of bear teeth worn as a necklace—grave goods common to Hopewell human burials—making this the only decorated burial of a wild cat found in North America, as well as the only animal buried alone in its own mound. Though the Hopewell had had domesticated dogs for hundreds of years, Perri says that having a tamed bobcat would have been “a very uncommon experience.”

|

Video:

|

Discovering a Bobkitten

|

World’s Oldest Pretzels

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, December 07, 2015

Archaeologists digging at the site of the future Museum of Bavarian History in Regensburg, Germany, expected their most exciting finds would date to the Roman era, but they were in for a surprise. In an eighteenth-century privy, they discovered the carbonized pieces of two pretzels. “We never have the opportunity to recover baked goods,” says government archaeologist Silvia Codreanu-Windauer. “Generally they were eaten, or, if burned, they were fed to dogs or chickens.” She speculates that in this case an absentminded baker or his apprentice forgot the pretzels in the oven and was so disgusted at burning them that he threw them in the toilet. It seems to have happened more than once. In the same privy, the team found the charred remains of three bread rolls and a fragment of a crescent-shaped local delicacy called a kipferl.

Archaeologists digging at the site of the future Museum of Bavarian History in Regensburg, Germany, expected their most exciting finds would date to the Roman era, but they were in for a surprise. In an eighteenth-century privy, they discovered the carbonized pieces of two pretzels. “We never have the opportunity to recover baked goods,” says government archaeologist Silvia Codreanu-Windauer. “Generally they were eaten, or, if burned, they were fed to dogs or chickens.” She speculates that in this case an absentminded baker or his apprentice forgot the pretzels in the oven and was so disgusted at burning them that he threw them in the toilet. It seems to have happened more than once. In the same privy, the team found the charred remains of three bread rolls and a fragment of a crescent-shaped local delicacy called a kipferl.

Mythological Mercury Pool

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, December 07, 2015

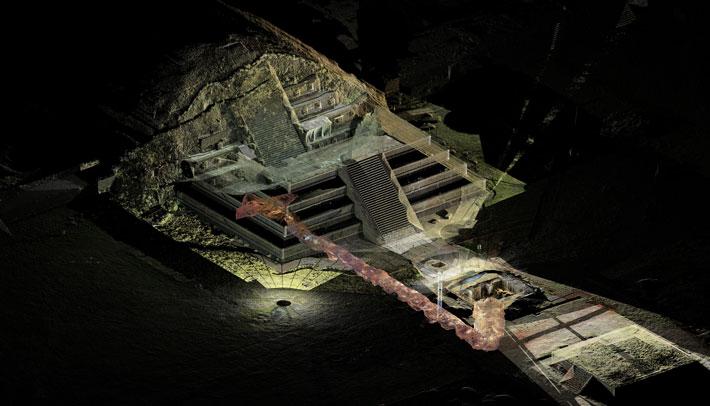

Mercury is often found in Mesoamerican tombs in the form of a powdery red pigment called cinnabar, but its liquid form is extremely rare. So it was with some surprise that Sergio Gomez, an archaeologist with Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, discovered traces of liquid mercury this year in three chambers under the early-third-century A.D. Feathered Serpent Pyramid in the ancient city of Teotihuacan. Gomez believes the mercury was part of a representation of the geography of the underworld, the mythological realm where the dead reside. The silvery liquid was probably used to depict lakes and rivers.

Since uncovering the entrance to a tunnel leading beneath the pyramid in 2003, Gomez has found five underground chambers containing thousands of artifacts, including many thought to be offerings, such as skeletons of large jaguars and wolves. Other objects, such as figurines made of jade from Guatemala and seashells from the Caribbean, indicate how far Teotihuacan’s influence extended. In addition to helping maintain the mercury in liquid form, the humidity and lack of oxygen in the underground chambers have preserved plant seeds and fragments of something that might be human skin.

Tracing Slave Origins

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, December 07, 2015

Researchers using a newly developed technique that permits the targeted retrieval of ancient genetic material were able to successfully identify the ethnic origins of three enslaved Africans found buried together on the Caribbean island of St. Martin, even though the surviving DNA was highly fragmented. Known locally as the Zoutsteeg Three, the two men and one woman (ages 25–40) had been found by construction workers in 2010. At that time, archaeologists were immediately struck by the condition of the individuals’ teeth, which had been intentionally filed down, a modification commonly associated with certain regions of Africa.

Researchers using a newly developed technique that permits the targeted retrieval of ancient genetic material were able to successfully identify the ethnic origins of three enslaved Africans found buried together on the Caribbean island of St. Martin, even though the surviving DNA was highly fragmented. Known locally as the Zoutsteeg Three, the two men and one woman (ages 25–40) had been found by construction workers in 2010. At that time, archaeologists were immediately struck by the condition of the individuals’ teeth, which had been intentionally filed down, a modification commonly associated with certain regions of Africa.

While DNA does not survive well in tropical environments, experts from the University of Copenhagen and Stanford University used whole-genome capture and next-generation sequencing to isolate the scant DNA remains of the Zoutsteeg Three. By comparing this evidence with the DNA of modern West African populations, they have learned that one of the slaves likely originated among the Bantu-speaking population of Cameroon, while the other two probably came from non-Bantu-speaking regions of Nigeria and Ghana. “We were able to show that we can use genome data to trace the genetic origins of enslaved Africans with far greater precision than previously thought possible,” says Hannes Schroeder of the University of Copenhagen. “This has important implications for the study of Caribbean slavery and the archaeology of the African diaspora.”

Jamestown’s VIPs

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, December 07, 2015

Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in the Americas, is perhaps the United States’ most consistently prolific archaeological site. This year researchers have analyzed four previously excavated graves found in the chancel of the original 1608 church, a burial location surely reserved for prominent figures. Scientific, forensic, and genealogical work identified the remains of four members of Jamestown’s leadership—and turned up at least one new mystery.

The Chaplain—Reverend Robert Hunt, the chaplain of the settlement, is thought to have died in 1608. His remains were wrapped in a shroud instead of a coffin, reflecting his piety, and he was buried facing the congregation.

The Soldier—By contrast, Captain William West, killed by Native Americans in 1610, was buried in an ornate coffin, of which only the nails remain. His bones had high lead content, due to use of high-status drinking vessels, and found with him were the delicate remnants of a silk military sash.

The Nobleman—An even more elaborate, human-shaped coffin held the remains of Sir Ferdinando Wainman, Jamestown’s master of ordnance, who died during the “starving time” of 1609–1610, when some 70 percent of the colonists perished. His remains also had the high lead content of an aristocrat.

The Explorer—Captain Gabriel Archer, another victim of the starving time, had explored much of the northeast coast of America before the colony was established. His grave contained a fragment of a staff carried by British officers, as well as a silver box holding human bone fragments and a lead ampulla—almost certainly a Catholic reliquary. Was Archer a secret Catholic in the Protestant colony, or was the box repurposed and given some new significance for the first American outpost of the Anglican Church?

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement