From the Trenches

Off the Grid

By MALIN GRUNBERG BANYASZ

Monday, December 07, 2015

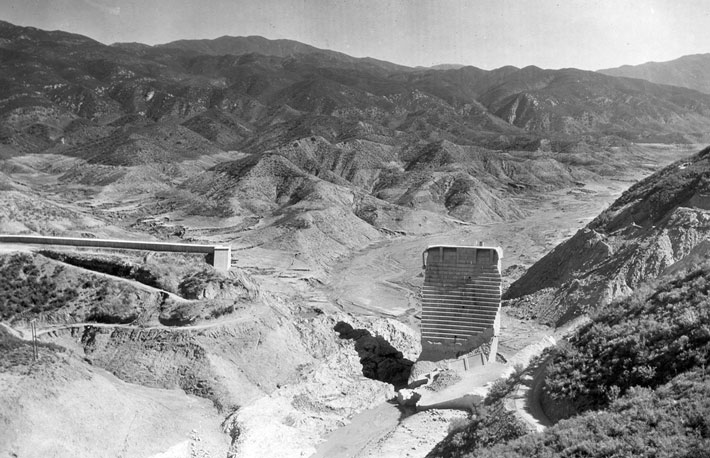

The history of Los Angeles’ water supply is long and complicated—remember Chinatown?—and continues through today’s drought crisis. In the early 1900s, William Mulholland, then superintendent of Los Angeles’ Water Department, oversaw the construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct to bring water to the city from Owens Valley, more than 200 miles away. About a decade later, he built the St. Francis Dam, in San Francisquito Canyon, to guard the city against drought and to generate hydroelectric power. St. Francis, a curved gravity dam like the later Hoover Dam, was completed in 1926. On March 12, 1928, two years to the day after the reservoir began to fill, the St. Francis Dam failed catastrophically, sending a wall of water through the towns of Piru, Fillmore, and Santa Paula that killed at least 450 people. The disaster, the result of flaws in construction, design, and location, is considered one of America’s greatest civil engineering failures. It ended Mulholland’s storied career and informed the construction of the Hoover Dam, which was completed in 1936. According to David S. Peebles, acting heritage manager for the Angeles National Forest, the recent 100-year anniversary of the Los Angeles Aqueduct sparked new interest in the protected historical site.

The history of Los Angeles’ water supply is long and complicated—remember Chinatown?—and continues through today’s drought crisis. In the early 1900s, William Mulholland, then superintendent of Los Angeles’ Water Department, oversaw the construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct to bring water to the city from Owens Valley, more than 200 miles away. About a decade later, he built the St. Francis Dam, in San Francisquito Canyon, to guard the city against drought and to generate hydroelectric power. St. Francis, a curved gravity dam like the later Hoover Dam, was completed in 1926. On March 12, 1928, two years to the day after the reservoir began to fill, the St. Francis Dam failed catastrophically, sending a wall of water through the towns of Piru, Fillmore, and Santa Paula that killed at least 450 people. The disaster, the result of flaws in construction, design, and location, is considered one of America’s greatest civil engineering failures. It ended Mulholland’s storied career and informed the construction of the Hoover Dam, which was completed in 1936. According to David S. Peebles, acting heritage manager for the Angeles National Forest, the recent 100-year anniversary of the Los Angeles Aqueduct sparked new interest in the protected historical site.

The site

The site

When 12.4 billion gallons of water surged through the narrow canyon, it scoured much of the dam site. The only portions left standing were part of the wing wall and a section of the middle of the dam, which was nicknamed “The Tombstone.” The next year that, too, was demolished. Today, the site is accessible to the public year-round, and can be reached from existing county roads. Visitors can see the narrow valley opening, portions of the wing wall and railings, and massive chunks of concrete that still have ridges remaining from the dam’s stair-stepped face. The U.S. Forest Service, Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, and California State University, Northridge, are all exploring the oral history and documentation of the site, and are making plans to excavate areas associated with dam and aqueduct construction, as well as provide additional interpretive signage for visitors.

While you’re there

Angeles National Forest is crisscrossed by hiking, riding, and biking trails that provide sweeping views of the San Gabriel Mountains, just north of the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society in Newhall gives an annual tour of the St. Francis Dam site, maintains a museum of local history, from the pioneers to the film industry, and gives regular tours of Heritage Junction Historic Park, a collection of relocated and restored historic buildings, including a train station.

Reading the Invisible Ink

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, December 07, 2015

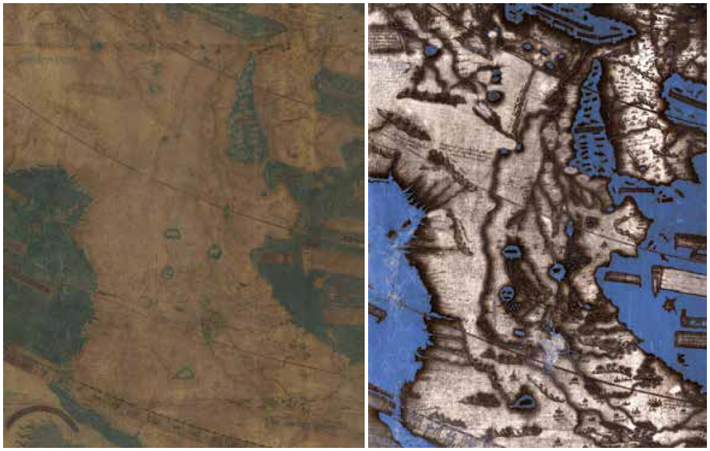

When Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean in 1492, he assumed he was in Japan. This was partly due to his fifteenth-century naïveté regarding world geography, but also because he had departed Spain armed with misinformation. It is believed that one of the sources that Columbus consulted before his journey was a map produced by German cartographer Henricus Martellus in 1491. The map locates Japan a thousand miles from the Asian mainland, where Columbus expected to find it on his way to the East Indies. The Martellus map reflected the sum total of European geographical knowledge at that time, and is considered by experts today to be one of the seminal maps of the Age of Discovery. “It seems to have influenced Columbus’ ideas about world geography, Martin Behaim’s terrestrial globe of 1492, and Martin Waldseemüller’s famous world map of 1507,” says map historian Chet Van Duzer. A recent project led by Van Duzer has used modern imaging technology to analyze the 525-year-old Martellus map, revealing details that provide a previously unseen glimpse into how Columbus and his peers perceived the world.

The existence of Martellus’ map was publicized in the 1960s when it was anonymously donated to Yale University. Measuring six feet by four feet, the map represents the Earth’s surface from the Atlantic in the west to the Pacific in the east—with Japan occupying the top right corner. Even as it was declared a vital piece of history, centuries of neglect and mistreatment had left many of the map’s details invisible. “Almost all of the text had faded to illegibility,” says Van Duzer, “making perhaps the most important map of the fifteenth century unstudiable.” Originally, the map was covered in dozens of Latin passages that described the people or characteristics of certain regions. Over the past two years, Van Duzer and his team have been recovering this information, bit by bit, with the help of multispectral imaging, which involves taking a series of photographs using a variety of frequencies of light, from ultraviolet to infrared. By stitching these images together and using digital enhancement tools, elements no longer visible to the naked eye can be seen. Similar techniques have been used recently to identify hidden details of Etruscan and Roman wall paintings, and to scrutinize ancient papyrus scrolls.

These newly revealed images attest to the ways in which fifteenth-century Europeans regarded unfamiliar lands. One passage over Asia reads, “Here are found the Hippopodes: They have a human form but the feet of horses.” Another in southern Asia describes the Panotii people, who had ears so large they could use them as sleeping bags. Text written over Africa declares, “Here there are large wildernesses in which there are lions, large leopards, and many other animals different from ours.” Now that these details have been brought to light, map historians can speculate not only on Martellus’ sources, but also on how he influenced later cartographers.

These newly revealed images attest to the ways in which fifteenth-century Europeans regarded unfamiliar lands. One passage over Asia reads, “Here are found the Hippopodes: They have a human form but the feet of horses.” Another in southern Asia describes the Panotii people, who had ears so large they could use them as sleeping bags. Text written over Africa declares, “Here there are large wildernesses in which there are lions, large leopards, and many other animals different from ours.” Now that these details have been brought to light, map historians can speculate not only on Martellus’ sources, but also on how he influenced later cartographers.

The new research has turned what was an “unstudiable” object into one that can finally be examined. As the use of imaging technology in ancient studies grows, it will have an impact both on new archaeological discoveries and on artifacts and sites uncovered centuries ago. “Multispectral imaging is a powerful tool for recovering texts from damaged manuscripts,” says Van Duzer. “I hope that it will prove useful in the study of damaged documents found in archaeological sites, and also perhaps in examining old texts that describe archaeological sites.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Top 10 Discoveries of 2015

The Many Lives of an English Manor House

Family History

Letter from Hawaii

From the Trenches

Reading the Invisible Ink

Off the Grid

Irish Roots

A Kestrel’s Last Meal

Pompeii Before the Romans

A Baltic Sea Monster Surfaces

Built upon Bones

An Opportunity for Early Humans in China

Hidden Blues

Mr. Jefferson’s Laboratory

Under a Haitian Palace

From Yacht to Trawler to Wreck

Buddha Stands Tall

Denmark’s Bog Dogs

Leftover Mammoth

Finding Parker’s Revenge

Living the Good Afterlife

Artifact

How a Medusa survived Christianity

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement