Features

Recovering Hidden Texts

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

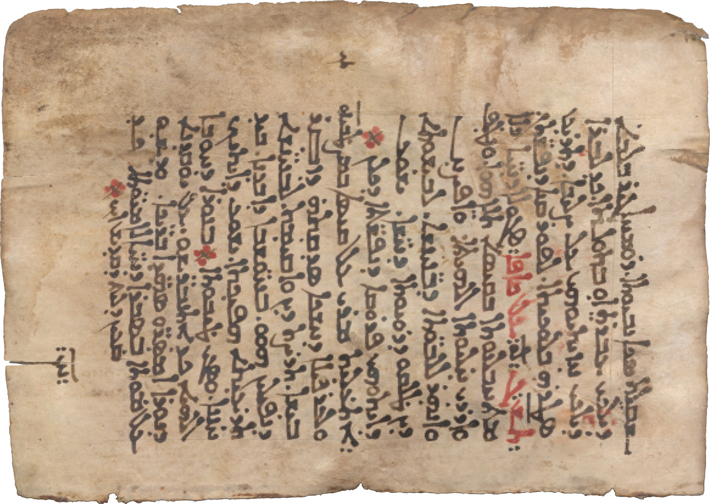

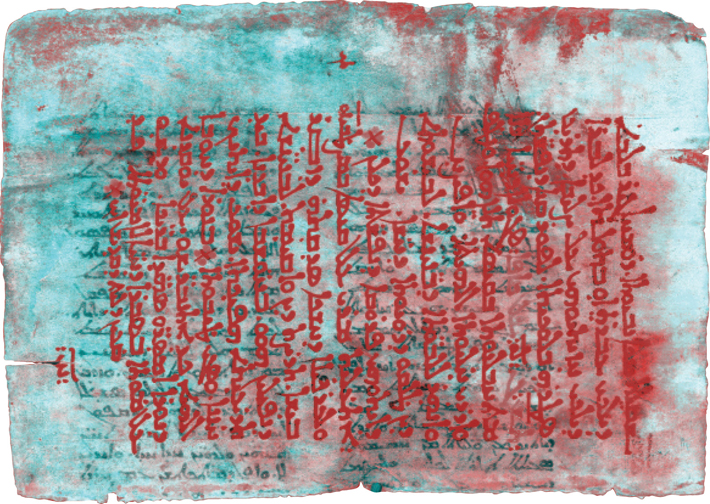

Sometime in the eighth century, a monk at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula was preparing to transcribe a book of the Bible in Arabic and needed fresh parchment. New parchment was an expensive commodity at the time and was difficult to obtain, especially for a humble monk copyist living in a remote desert monastery. Luckily for him, the venerable religious community had a massive library that included books that were no longer in use. These manuscripts, some written in extinct languages, or thought to be unimportant, were valued only for their potential as sources of recycled parchment. No one in the monastery would have thought twice, for instance, when, while searching for writing material, the monk plucked out of the collection an ancient Greek text that had gone unread for a generation or more. None of his brothers would have batted an eye as he used a knife to carefully scrape away the centuries-old ink. Soon, the words were gone and the parchment was ready for the monk’s fresh transcription of Bible verses. Today, erasing an ancient text seems an incalculable loss, but to the eighth-century scribe, it was an act of devotion and even a measure of progress—an obsolete text was gone, and a holy manuscript that would enrich countless spiritual lives was left in its place.

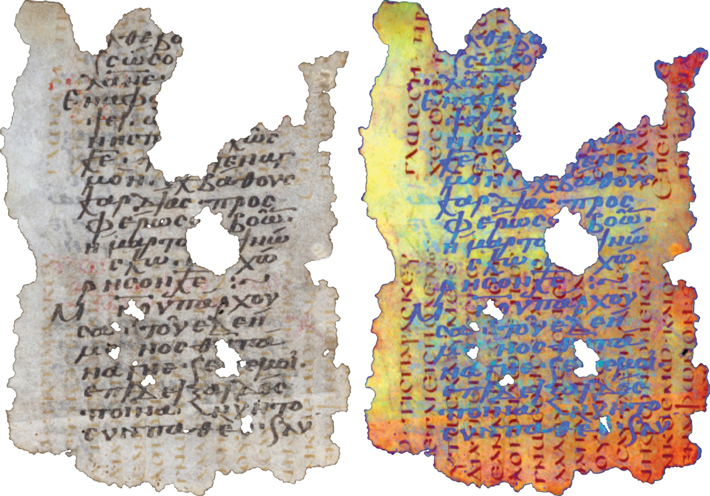

The original words on this reused text, or palimpsest, have been lost for over a thousand years. But now with the help of modern multispectral imaging technology, a team of scientists and scholars is able to peer through the manuscript’s visible ink and read the long-vanished text below. The library at St. Catherine’s contains well over a hundred such palimpsests, each one offering vivid new glimpses of the early Christian era. Later this year, after a large number of the palimpsests have been studied and translated by specialists, the monastery will make them available online, meaning that texts that have gone unread for a millennia can be pored over by scholars and interested laypeople from all over the world. “These are cultural treasures that are important to our common history,” says Michael Phelps, executive director of the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, which works with the UCLA Library to coordinate the project. “We’re helping recover lost communities that made important spiritual and literary contributions, and allowing their voices to speak again.”

The original words on this reused text, or palimpsest, have been lost for over a thousand years. But now with the help of modern multispectral imaging technology, a team of scientists and scholars is able to peer through the manuscript’s visible ink and read the long-vanished text below. The library at St. Catherine’s contains well over a hundred such palimpsests, each one offering vivid new glimpses of the early Christian era. Later this year, after a large number of the palimpsests have been studied and translated by specialists, the monastery will make them available online, meaning that texts that have gone unread for a millennia can be pored over by scholars and interested laypeople from all over the world. “These are cultural treasures that are important to our common history,” says Michael Phelps, executive director of the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, which works with the UCLA Library to coordinate the project. “We’re helping recover lost communities that made important spiritual and literary contributions, and allowing their voices to speak again.”

|

Sidebar:

|

The Bible Hunters

|

France’s Roman Heritage

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

The Roman city of Arelate, today known as Arles, France, was one of the most important ports of the later Roman Empire. After siding with Julius Caesar during his civil war against Pompey, the town was formally established as a Roman colony for Caesar’s veterans in 46 or 45 B.C. Strategically located along the Rhône River in southern Gaul, Arelate developed into such a major economic, political, and cultural center that it was referred to as the “little Rome of the Gauls” by the fourth-century poet Ausonius.

The Roman city of Arelate, today known as Arles, France, was one of the most important ports of the later Roman Empire. After siding with Julius Caesar during his civil war against Pompey, the town was formally established as a Roman colony for Caesar’s veterans in 46 or 45 B.C. Strategically located along the Rhône River in southern Gaul, Arelate developed into such a major economic, political, and cultural center that it was referred to as the “little Rome of the Gauls” by the fourth-century poet Ausonius.

Today, the city’s left bank, which served as the Roman settlement’s civic and administrative heart, is strewn with the remnants of ancient monuments: a theater, an amphitheater, baths, and a circus. It has long been thought that the city’s right bank was far less developed in the early Roman period, only witnessing significant growth decades or centuries later. However, this perception of ancient Arles is beginning to change as an ongoing investigation uncovers parts of a wealthy Roman residential area, providing new evidence of the early development of Arles’ periphery and also revealing some of the finest Roman wall paintings found anywhere in France.

A project led by the Museum of Ancient Arles is in the middle of a multiyear campaign to excavate the site of an eighteenth-century glassworks factory in the Trinquetaille district along Arles’ right bank. The glassworks complex—itself a designated historic site—was acquired by the city in the late 1970s. During the initial excavation of the property in the 1980s, archaeologists discovered a second-century A.D. Roman residential neighborhood buried beneath it, but the investigation was short-lived.

Over the past two years, a plan for rehabilitating and restoring the site has brought archaeologists back for the first time in decades. According to lead archaeologist Marie-Pierre Rothé, the renewed excavation has allowed researchers to dig deeper beneath the property and to unravel the surprisingly early history of the site. Beneath at least one Roman house discovered in the 1980s lies the much earlier foundation of an opulent Roman property dating back to the first decades of the Roman colony. Researchers know that as the new colony was incorporated into the Roman political and economic system, there was a sudden influx of wealth into the city, along with opportunities for advancement for both locals and Romans who migrated there. “One of our objectives,” says Rothé, “is to better understand the development of the Roman city of Arles during this early period in a neighborhood that was assumed to have been deserted.”

The discovery of this first-century B.C. domus, or home, is remarkable not only because it dates to a time when archaeologists believed the Trinquetaille area was void of such structures, but also for the quality of the house’s wall paintings. Its frescoes were designed in the Second Pompeian Style, according to August Mau’s nineteenth-century classification of the four major styles of Roman painting. The Second Style, which dates to between 70 and 20 B.C. in Roman Gaul, frequently used trompe l’oeil composition and painted architectural elements such as columns, windows, and marble panels to create the illusion of three-dimensional masonry. Although paintings such as these are common in Italy, especially Pompeii, they are rare in France, where only around 20 known examples exist. The excavations in Trinquetaille have uncovered the best in situ Second Style paintings in France, thanks to the preservation of a nearly five-foot-tall Roman wall to which the frescoes are still attached.

The discovery of this first-century B.C. domus, or home, is remarkable not only because it dates to a time when archaeologists believed the Trinquetaille area was void of such structures, but also for the quality of the house’s wall paintings. Its frescoes were designed in the Second Pompeian Style, according to August Mau’s nineteenth-century classification of the four major styles of Roman painting. The Second Style, which dates to between 70 and 20 B.C. in Roman Gaul, frequently used trompe l’oeil composition and painted architectural elements such as columns, windows, and marble panels to create the illusion of three-dimensional masonry. Although paintings such as these are common in Italy, especially Pompeii, they are rare in France, where only around 20 known examples exist. The excavations in Trinquetaille have uncovered the best in situ Second Style paintings in France, thanks to the preservation of a nearly five-foot-tall Roman wall to which the frescoes are still attached.

While some sections of the frescoes still remain in situ, most of the painted plaster must be retrieved from the debris and fill layers. Archaeologists now have hundreds of boxes containing thousands of fragments that need to be pieced back together like a giant jigsaw puzzle. Although this process will take years to complete, large portions of the painted ceilings and walls are already being reconstructed.

Öland, Sweden. Spring, A.D. 480

By ANDREW CURRY

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

The scene might have been lifted from the pages of a Scandinavian crime novel: Under a steely sky, a half-dozen skeletons emerge from the cold, wet earth. A strip of yellow and blue tape, fluttering in the wind blowing in from the Baltic Sea, holds back curious onlookers. Portable fences, the kind that go up around construction sites, form a protective ring-within-a-ring around the scene. Yellow plastic stakes mark the spots where bodies, some with clear evidence of brutal blows to the head with an ax or other edged weapon, have already been found.

Slowly, trowelful by trowelful, a 12-person team of investigators is excavating the scene of a gruesome mass murder on Öland, an island several miles off the coast of Sweden. In the last five years, they’ve found body after body, sprawled out with many of their bones shattered, on the rough limestone slabs and gravel floor of a 1,500-square-foot house. But it’s a cold case.

The floor is part of a house—the scene of the crime—surrounded by an oval ring of stones and earth, the remains of what was once a wall. Built around A.D. 400, it encircled an area the size of a football field. Now called Sandby Borg, the site is one of more than a dozen similar “borgs,” or forts, on Öland, all built during the Migration Period, a tumultuous era in Europe that began in the fourth century A.D. and hastened the collapse of the Roman Empire. The forts were like safe rooms in case of a siege or surprise attack and could be reached within a few minutes at a dead run from surrounding farms. Sandby Borg’s 15-foot-high ramparts once protected 53 houses and their stores of food. What remains of Sandby Borg’s walls now surround a flat expanse of grass, and aren’t even tall enough to break the strong winds. But 1,500 years ago, Sandby Borg would have been impossible to miss.

Despite its defensive advantages, its end was violent and swift. In a sudden onslaught not long after its construction, its residents were slaughtered, with just enough warning before the attack to hide their valuables. Their bodies were left where they lay, on the floors of their homes and even in smoldering fire pits. The houses were closed up and the place was abandoned. It wasn’t looted after the murders, and neighbors on the densely populated island didn’t interfere with the site, so archaeologists believe that the area was considered taboo for years after the attack. As the turf walls of its houses collapsed, Sandby Borg became a shallow grave, with bones concealed just inches below the surface. It’s unique, says Helena Victor, an archaeologist at the Kalmar County Museum on the mainland just across from the island, because the attack and destruction were so sudden, and the site was never resettled. “This intact moment of an ordinary day is very important, because we know so little about daily life at this time,” she says.

The Sandby Borg project began in 2010 in response to the threat of looting. Researchers at that time had little idea of what they would actually find. Archaeologists testing geophysical prospecting methods in the area noticed that treasure hunters had recently dug pits around the fort, perhaps looking for gold coins. Professional metal detectorists were mobilized to search for anything the looters had missed. They uncovered five different jewelry stashes from houses at the center of the fort. The caches include silver brooches and bells, gold rings, and amber and glass beads. There were even cowrie shell fragments, pierced to be strung on a necklace.

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Öland, Sweden. Spring, A.D. 480

France’s Roman Heritage

Recovering Hidden Texts

Letter from Guatemala

From the Trenches

Legends of Glastonbury Abbey

Off the Grid

A Circle of Skulls

Medieval Russian Memo

The Ring’s the Thing

Chinatown before the Quake

Tomb from a Lost Tribe

Alfred the Great’s Forgotten Ally

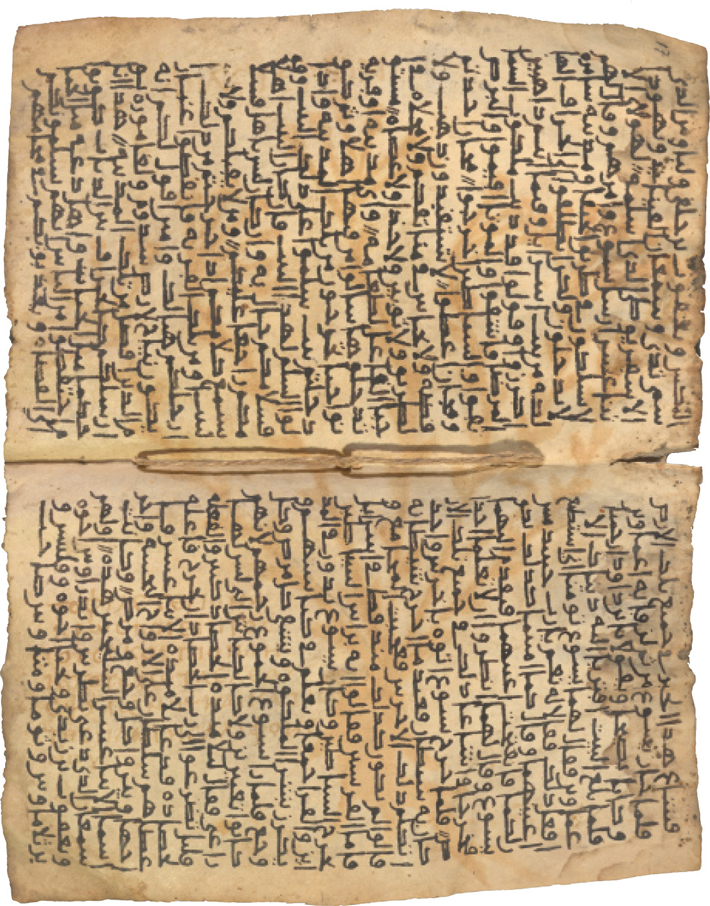

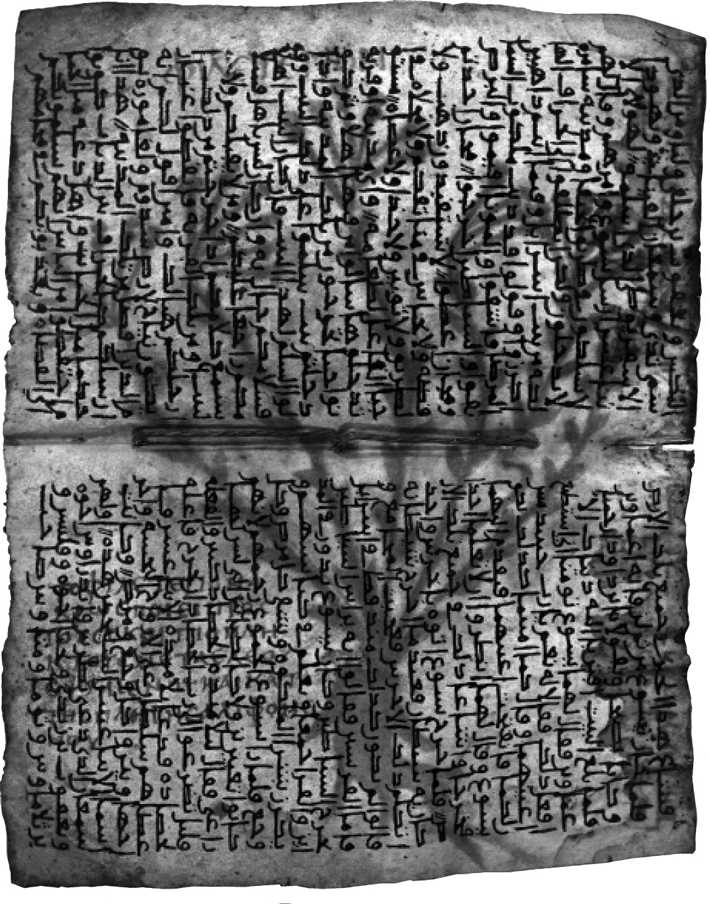

Reading an Inca Archive

Minding the Beeswax

Quarrying Stonehenge

A Viral Fingerprint

Caesar’s Diplomatic Breakdown

Ship Underground

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

The monastery has a rich collection of icons and other religious objects, but it is most famous for its library, which, with more than 3,300 manuscripts, is second only to that of the Vatican in terms of the number of ancient texts it contains. While the Vatican library was assembled carefully over the centuries, St. Catherine’s collection is different, more eclectic. “The Sinai library differs from most libraries in that it grew organically to provide the monks with copies of the scriptures and books that would inspire and guide them in their dedication,” says Father Justin, who serves as the monastery’s librarian. Many of the monks and pilgrims who came to the monastery over the centuries left manuscripts as gifts, resulting in an especially idiosyncratic collection. In addition to important Christian texts, the library contains, for instance, one of the world’s earliest known copies of the Iliad.

The monastery has a rich collection of icons and other religious objects, but it is most famous for its library, which, with more than 3,300 manuscripts, is second only to that of the Vatican in terms of the number of ancient texts it contains. While the Vatican library was assembled carefully over the centuries, St. Catherine’s collection is different, more eclectic. “The Sinai library differs from most libraries in that it grew organically to provide the monks with copies of the scriptures and books that would inspire and guide them in their dedication,” says Father Justin, who serves as the monastery’s librarian. Many of the monks and pilgrims who came to the monastery over the centuries left manuscripts as gifts, resulting in an especially idiosyncratic collection. In addition to important Christian texts, the library contains, for instance, one of the world’s earliest known copies of the Iliad.

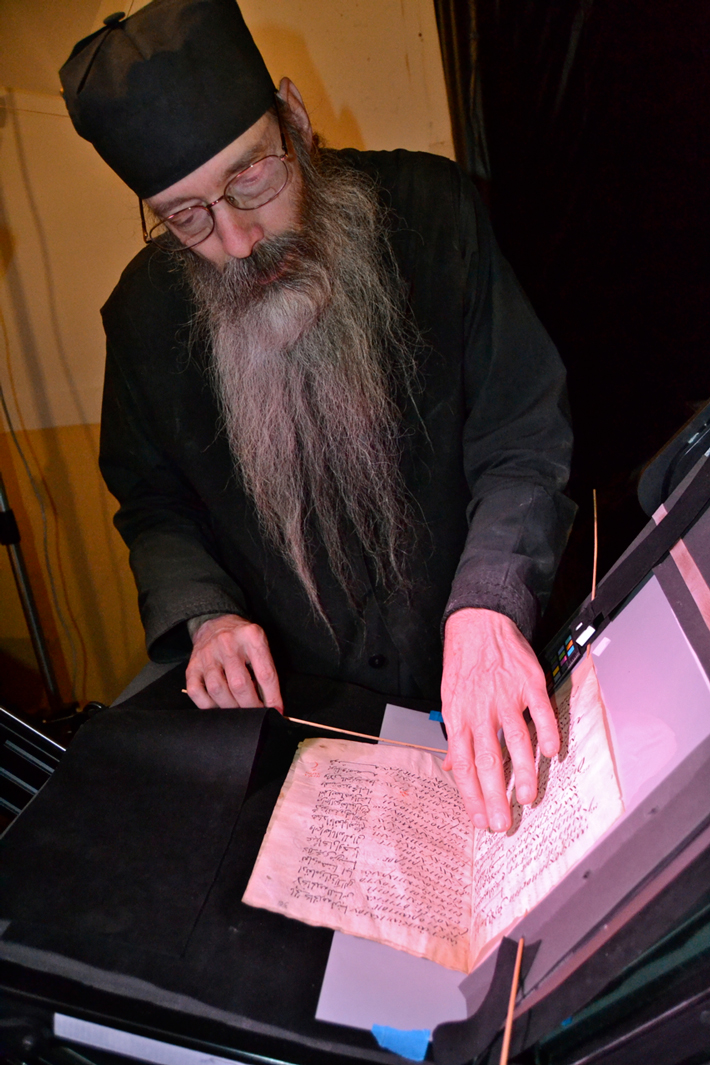

Father Justin learned of an ambitious scientific and scholarly effort under way from 1998 to 2008 to use multispectral imaging technologies to read the Archimedes Palimpsest, a tenth-century copy of the great Greek philosopher’s writings that had been overwritten by thirteenth-century Christian monks. He contacted the team decoding the Archimedes Palimpsest, and soon many of the scientists involved in the project agreed to again pool their resources to read the Sinai palimpsests. Organization of the project fell to Phelps and the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, which uses digital technology to make ancient manuscripts available online to both scholars and the general public.

Father Justin learned of an ambitious scientific and scholarly effort under way from 1998 to 2008 to use multispectral imaging technologies to read the Archimedes Palimpsest, a tenth-century copy of the great Greek philosopher’s writings that had been overwritten by thirteenth-century Christian monks. He contacted the team decoding the Archimedes Palimpsest, and soon many of the scientists involved in the project agreed to again pool their resources to read the Sinai palimpsests. Organization of the project fell to Phelps and the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, which uses digital technology to make ancient manuscripts available online to both scholars and the general public.

Those works hint at how the monks may have understood and treated illnesses, a very practical dimension of their lives, but the team has also found evidence that at least some monks could have relied on the library for pleasure reading. They have identified a palimpsest containing the illustrated version of a secular fictional work, the oldest known non-biblical illustrated manuscript, perhaps suggesting that monks may have not confined themselves to religious reading.

Those works hint at how the monks may have understood and treated illnesses, a very practical dimension of their lives, but the team has also found evidence that at least some monks could have relied on the library for pleasure reading. They have identified a palimpsest containing the illustrated version of a secular fictional work, the oldest known non-biblical illustrated manuscript, perhaps suggesting that monks may have not confined themselves to religious reading.

As archaeologists have explored House 40, they’ve uncovered some fascinating details. The team has found lamb bones that place the fort’s final days in the spring. Grains of rye and the earliest mustard seeds yet found in Scandinavia hint at what else might have been on the table. “We’ve even found the skeleton of half a herring, perhaps part of a last meal,” says Victor. “It’s a kind of frozen moment you almost never have.” Clara Alfsdotter, an osteologist at the Bohusläns County Museum in Uddevalla, Sweden, took soil samples from near the stomachs of several skeletons and will send them to a lab in Stockholm. “Hopefully we can see what they consumed before they died,” she says.

As archaeologists have explored House 40, they’ve uncovered some fascinating details. The team has found lamb bones that place the fort’s final days in the spring. Grains of rye and the earliest mustard seeds yet found in Scandinavia hint at what else might have been on the table. “We’ve even found the skeleton of half a herring, perhaps part of a last meal,” says Victor. “It’s a kind of frozen moment you almost never have.” Clara Alfsdotter, an osteologist at the Bohusläns County Museum in Uddevalla, Sweden, took soil samples from near the stomachs of several skeletons and will send them to a lab in Stockholm. “Hopefully we can see what they consumed before they died,” she says.