Features

An Overlooked Inca Wonder

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, April 05, 2016

Members of the public regularly get in touch with Charles Stanish, an expert on Andean cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. Two years ago, Stanish received a call from a man in Pittsburgh who had just seen a program claiming that aliens played a large role in the lives of ancient people. He was interested in getting Stanish’s take on a particular Peruvian site purported to be the handiwork of extraterrestrials. “I always try to be nice to people like that,” says Stanish. “For whatever reason, they are interested in the ancient past, and I share with them what archaeologists know about the subject.” In this case, the man asked Stanish what he thought about the idea of aliens constructing a strange alignment of pits, known popularly as the “Band of Holes,” in Peru’s Pisco Valley. Though he has worked in the area for more than 30 years, Stanish had never heard of the site. He and his colleague Henry Tantaleán took a look at its coordinates on Google Earth for themselves, and were surprised by satellite imagery showing that the Band of Holes is indeed a highly unusual artificial feature. It seemed to be made up of thousands of small depressions running upslope. “I’d never seen anything like it,” says Stanish. “It really seemed unique.” It was also only 10 miles from Stanish and Tantaleán’s own excavations in the nearby Chincha Valley. Intrigued, they decided to try to understand the curious site.

Members of the public regularly get in touch with Charles Stanish, an expert on Andean cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. Two years ago, Stanish received a call from a man in Pittsburgh who had just seen a program claiming that aliens played a large role in the lives of ancient people. He was interested in getting Stanish’s take on a particular Peruvian site purported to be the handiwork of extraterrestrials. “I always try to be nice to people like that,” says Stanish. “For whatever reason, they are interested in the ancient past, and I share with them what archaeologists know about the subject.” In this case, the man asked Stanish what he thought about the idea of aliens constructing a strange alignment of pits, known popularly as the “Band of Holes,” in Peru’s Pisco Valley. Though he has worked in the area for more than 30 years, Stanish had never heard of the site. He and his colleague Henry Tantaleán took a look at its coordinates on Google Earth for themselves, and were surprised by satellite imagery showing that the Band of Holes is indeed a highly unusual artificial feature. It seemed to be made up of thousands of small depressions running upslope. “I’d never seen anything like it,” says Stanish. “It really seemed unique.” It was also only 10 miles from Stanish and Tantaleán’s own excavations in the nearby Chincha Valley. Intrigued, they decided to try to understand the curious site.

Together, Stanish and Tantaleán speculated as to what the Band of Holes might have been. They reasoned it could have been part of a defensive structure, or served as a marker for a trail, or might even be a geoglyph in the tradition of the nearby Nazca lines. In searching the archaeological literature, they found that the site had first been documented in 1931 by aerial photographer and geographer Robert Shippee. Since then, a few archaeologists had visited and described it as being made up of segments of shallow holes running a mile up a hill known as Monte Sierpe. The consensus seemed to be that the holes were made to store something, but exactly what remained unclear. Despite the fact that previous generations of archaeologists knew about the site, no excavations had been conducted, and no obvious artifacts had been found near the holes. There was no agreement on when it was built or by what culture. For Stanish and Tantaleán, the mystery was deepening.

In the 2015 field season, Stanish set up his team in the Chincha Valley and then drove with Tantaleán to Monte Sierpe. From below, the row upon row of holes creeping up the slope made for an imposing view. “Really, it is very impressive,” says Tantaleán. “I’d never seen anything like it in my entire career.” They quickly found a small amount of pottery dating to just before the time the Spanish invaded Peru, when the Inca ruled this part of it. There were also other signs it could be an Inca site. “I began to suspect it dated to the Inca period because at the base of the site there are tombs similar to those in the Chincha Valley that date to the time of the Incas,” says Tantaleán.

The World's Oldest Writing

By THE EDITORS

Tuesday, April 05, 2016

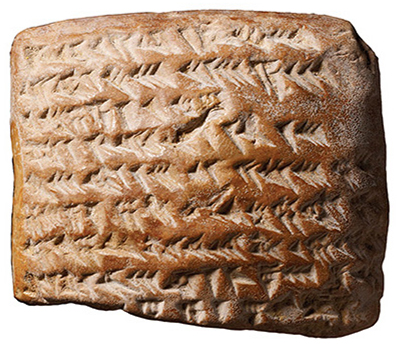

In early 2016, hundreds of media outlets around the world reported that a set of recently deciphered ancient clay tablets revealed that Babylonian astronomers were more sophisticated than previously believed. The wedge-shaped writing on the tablets, known as cuneiform, demonstrated that these ancient stargazers used geometric calculations to predict the motion of Jupiter. Scholars had assumed it wasn’t until almost A.D. 1400 that these techniques were first employed—by English and French mathematicians. But here was proof that nearly 2,000 years earlier, ancient people were every bit as advanced as Renaissance-era scholars. Judging by the story’s enthusiastic reception on social media, this discovery captured the public imagination. It implicitly challenged the perception that cuneiform tablets were used merely for basic accounting, such as tallying grain, rather than for complex astronomical calculations. While most tablets were, in fact, used for mundane bookkeeping or scribal exercises, some of them bear inscriptions that offer unexpected insights into the minute details of and momentous events in the lives of ancient Mesopotamians.

In early 2016, hundreds of media outlets around the world reported that a set of recently deciphered ancient clay tablets revealed that Babylonian astronomers were more sophisticated than previously believed. The wedge-shaped writing on the tablets, known as cuneiform, demonstrated that these ancient stargazers used geometric calculations to predict the motion of Jupiter. Scholars had assumed it wasn’t until almost A.D. 1400 that these techniques were first employed—by English and French mathematicians. But here was proof that nearly 2,000 years earlier, ancient people were every bit as advanced as Renaissance-era scholars. Judging by the story’s enthusiastic reception on social media, this discovery captured the public imagination. It implicitly challenged the perception that cuneiform tablets were used merely for basic accounting, such as tallying grain, rather than for complex astronomical calculations. While most tablets were, in fact, used for mundane bookkeeping or scribal exercises, some of them bear inscriptions that offer unexpected insights into the minute details of and momentous events in the lives of ancient Mesopotamians.

First developed around 3200 B.C. by Sumerian scribes in the ancient city-state of Uruk, in present-day Iraq, as a means of recording transactions, cuneiform writing was created by using a reed stylus to make wedge-shaped indentations in clay tablets. Later scribes would chisel cuneiform into a variety of stone objects as well. Different combinations of these marks represented syllables, which could in turn be put together to form words. Cuneiform as a robust writing tradition endured 3,000 years. The script—not itself a language—was used by scribes of multiple cultures over that time to write a number of languages other than Sumerian, most notably Akkadian, a Semitic language that was the lingua franca of the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires.

After cuneiform was replaced by alphabetic writing sometime after the first century A.D., the hundreds of thousands of clay tablets and other inscribed objects went unread for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until the early nineteenth century, when archaeologists first began to excavate the tablets, that scholars could begin to attempt to understand these texts. One important early key to deciphering the script proved to be the discovery of a kind of cuneiform Rosetta Stone, a circa 500 B.C. trilingual inscription at the site of Bisitun Pass in Iran. Written in Persian, Akkadian, and an Iranian language known as Elamite, it recorded the feats of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great (r. 521–486 B.C.). By deciphering repetitive words such as “Darius” and “king” in Persian, scholars were able to slowly piece together how cuneiform worked. Called Assyriologists, these specialists were eventually able to translate different languages written in cuneiform across many eras, though some early versions of the script remain undeciphered.

After cuneiform was replaced by alphabetic writing sometime after the first century A.D., the hundreds of thousands of clay tablets and other inscribed objects went unread for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until the early nineteenth century, when archaeologists first began to excavate the tablets, that scholars could begin to attempt to understand these texts. One important early key to deciphering the script proved to be the discovery of a kind of cuneiform Rosetta Stone, a circa 500 B.C. trilingual inscription at the site of Bisitun Pass in Iran. Written in Persian, Akkadian, and an Iranian language known as Elamite, it recorded the feats of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great (r. 521–486 B.C.). By deciphering repetitive words such as “Darius” and “king” in Persian, scholars were able to slowly piece together how cuneiform worked. Called Assyriologists, these specialists were eventually able to translate different languages written in cuneiform across many eras, though some early versions of the script remain undeciphered.

Today, the ability to read cuneiform is the key to understanding all manner of cultural activities in the ancient Near East—from determining what was known of the cosmos and its workings, to the august lives of Assyrian kings, to the secrets of making a Babylonian stew. Of the estimated half-million cuneiform objects that have been excavated, many have yet to be catalogued and translated. Here, a few fine and varied examples of some of the most interesting ones that have been.

Today, the ability to read cuneiform is the key to understanding all manner of cultural activities in the ancient Near East—from determining what was known of the cosmos and its workings, to the august lives of Assyrian kings, to the secrets of making a Babylonian stew. Of the estimated half-million cuneiform objects that have been excavated, many have yet to be catalogued and translated. Here, a few fine and varied examples of some of the most interesting ones that have been.

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Dressing for the Ages

Off the Grid

Let a Turtle Be Your Psychopomp

The Price of Tea in China

What Happened After 1492?

Women in a Temple of Death

Islam North of the Pyrenees

Mesolithic Markings

Vikings, Worms, and Emphysema

Medieval River Engineering

The Death of Joe the Quilter

Egypt’s Immigrant Elite

The First Casus Belli

Artifact

The Wild Man of the medieval world

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Back at UCLA, Stanish attended a lecture given by Harvard University archaeologist Gary Urton. Urton spoke about recent discoveries at the Inca site of Inkawasi, which is about 75 miles north of Monte Sierpe. The Peruvian archaeologist Alejandro Chu had found a number of the knotted-string recording devices known as khipus in colcas there. Many of the khipus were associated with the remains of various agricultural produce, such as peanuts and chilies, that had been laid out on a floor that was divided like a checkerboard (see “

Back at UCLA, Stanish attended a lecture given by Harvard University archaeologist Gary Urton. Urton spoke about recent discoveries at the Inca site of Inkawasi, which is about 75 miles north of Monte Sierpe. The Peruvian archaeologist Alejandro Chu had found a number of the knotted-string recording devices known as khipus in colcas there. Many of the khipus were associated with the remains of various agricultural produce, such as peanuts and chilies, that had been laid out on a floor that was divided like a checkerboard (see “ If, in fact, the thousands of holes at the site were dug in order to measure tribute, the Band of Holes might be suggestive of the inner workings of the Inca Empire. “Troops were, of course, the blunt force of the state’s power,” says Urton. “But it was the khipukamayuqs who really established and maintained control over the regions.” Simply being conquered by the Inca didn’t make one a citizen of the empire, but paying taxes certainly did. And pouring beans and chilies into holes in front of state accountants would have brought the average farmer in the Pisco Valley face to face with the power of the state. “Inca accounting practices were the keys to maintaining control over the empire,” says Urton. “Khipukamayuqs really shaped the world of the Incas’ subjects.”

If, in fact, the thousands of holes at the site were dug in order to measure tribute, the Band of Holes might be suggestive of the inner workings of the Inca Empire. “Troops were, of course, the blunt force of the state’s power,” says Urton. “But it was the khipukamayuqs who really established and maintained control over the regions.” Simply being conquered by the Inca didn’t make one a citizen of the empire, but paying taxes certainly did. And pouring beans and chilies into holes in front of state accountants would have brought the average farmer in the Pisco Valley face to face with the power of the state. “Inca accounting practices were the keys to maintaining control over the empire,” says Urton. “Khipukamayuqs really shaped the world of the Incas’ subjects.”