Cuneiform

Last Tablets

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

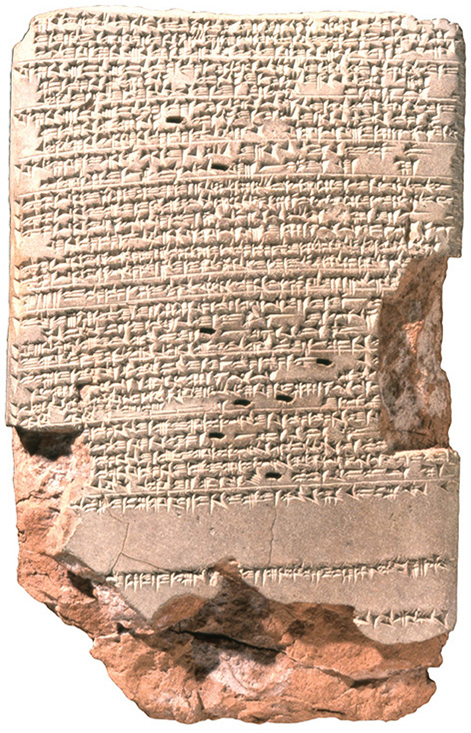

Though Akkadian as a spoken language in Mesopotamia died out toward the end of the first millennium B.C., cuneiform continued to be used by temple scribes and astrologers. Greek scholars are known to have flocked to Babylon during this time to learn astronomy, and excavated tablets inscribed in both Greek and Akkadian show that at least a few of these visiting astronomers even tried to master the art of writing cuneiform. But the end was near. The last known tablets that can be dated were written in the late first century A.D. Some scholars believe cuneiform ceased to be used around that time, but Assyriologist Markham Geller of the Free University of Berlin believes it endured for another two centuries. He points to classical sources that mention that Babylonian temples continued to thrive, and believes that they would have maintained scribes still capable of reading and writing cuneiform to ensure that rituals were properly performed. He also thinks cuneiform medical texts may have continued to be used to diagnose illnesses during this era.

Though Akkadian as a spoken language in Mesopotamia died out toward the end of the first millennium B.C., cuneiform continued to be used by temple scribes and astrologers. Greek scholars are known to have flocked to Babylon during this time to learn astronomy, and excavated tablets inscribed in both Greek and Akkadian show that at least a few of these visiting astronomers even tried to master the art of writing cuneiform. But the end was near. The last known tablets that can be dated were written in the late first century A.D. Some scholars believe cuneiform ceased to be used around that time, but Assyriologist Markham Geller of the Free University of Berlin believes it endured for another two centuries. He points to classical sources that mention that Babylonian temples continued to thrive, and believes that they would have maintained scribes still capable of reading and writing cuneiform to ensure that rituals were properly performed. He also thinks cuneiform medical texts may have continued to be used to diagnose illnesses during this era.

But in the third century A.D., the neighboring Sassanian Empire, known to be hostile to foreign religions, seized Babylon. “They shut the temples down,” says Geller, “and they sent everyone home.” He believes it was only when the very last of these temple scribes died that the rich, 3,000-year-old cuneiform record finally fell silent.

Warfare

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

During the millennia in which cuneiform script was used, Mesopotamia saw city-states jockey for resources, empires grow and dissipate, and seemingly countless kings made and unmade on the battlefield. Successful military campaigns brought land and resources, affirmed royal power, and granted privileged access to the gods. In turn, sculptures, reliefs, and cuneiform writings were commissioned to memorialize victories and legitimize claims. The Stela of the Vultures documents one of these conflicts from Sumer’s Early Dynastic III period (2600–2350 B.C.). “The monument stands at the beginning of a long line of historical narratives in the history of art,” says Irene J. Winter, a professor emeritus at Harvard University, in her analysis of the stela.

During this period, Sumer was a collection of city-states surrounded by agricultural land. As the city-states grew, so did the potential for border conflicts, such as one that raged for 200 years between Lagash and Umma, both in present-day Iraq. The Stela of the Vultures, which survives as seven fragments of what was once a six-foot slab of limestone, records Lagash’s eventual victory. One side depicts the god Ningirsu, holding his enemies in a sack, while the other shows a series of scenes from the conflict. A cuneiform account by Lagash’s leader, Eannatum, wraps around the stela: “Eannatum struck at Umma,” it reads. “The bodies were soon 3,600 in number....I, Eannatum, like a fierce storm wind, I unleashed the tempest!”

The historical side depicts Eannatum leading a phalanx of soldiers trampling enemies underfoot, a victory parade, a funeral ceremony, and another, poorly preserved tableau—along with, at top, the image that gives the stela its name, a kettle of vultures consuming the heads of Umma soldiers. It is, in a way, a document both poetic and legal—it invokes the grace and power of Ningirsu, and stakes a claim to land won by force.

Lagash’s primacy was short-lived. By the end of the period, Umma had plundered its rival and begun the consolidation of power that would result in the rise of the Akkadian Empire. The tradition of documenting battles in words and pictures continued, perhaps reaching a peak with the Assyrians in the seventh century B.C., when they carved elaborate battle reliefs in the North Palace of Nineveh in present-day Iraq, and documented the siege of Jerusalem on a series of octagonal clay prisms called Sennacherib’s Annals.

Religion

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

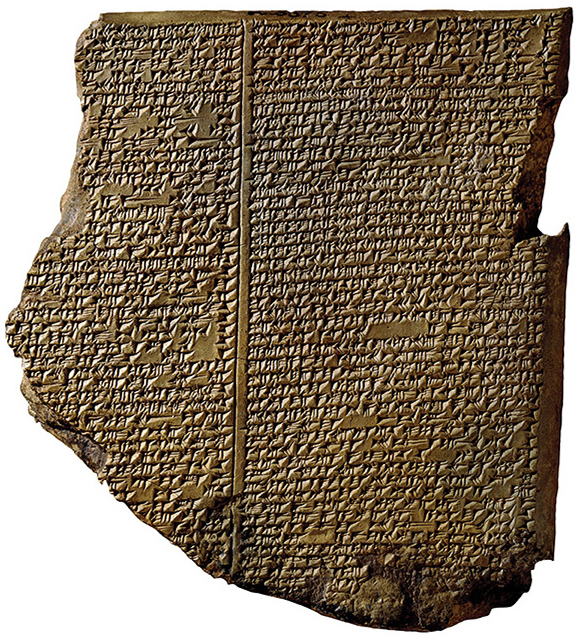

In November 1872, a self-taught Assyriologist named George Smith working as an assistant at the British Museum happened upon a fragment of a tablet that would soon become the most famous cuneiform text in the world. One of thousands excavated decades earlier at Nineveh, in present-day Iraq, the tablet told a story eerily similar to that of Noah in the Old Testament. In it, the gods resolve to destroy the world and all life with a great flood, but one of the chief gods warns one man in time to prevent the extinction of all living things: “Demolish the house, build a boat!” the god urges. “Abandon riches and seek survival! Spurn property and save life! Put on board the boat the seed of all living creatures!”

In November 1872, a self-taught Assyriologist named George Smith working as an assistant at the British Museum happened upon a fragment of a tablet that would soon become the most famous cuneiform text in the world. One of thousands excavated decades earlier at Nineveh, in present-day Iraq, the tablet told a story eerily similar to that of Noah in the Old Testament. In it, the gods resolve to destroy the world and all life with a great flood, but one of the chief gods warns one man in time to prevent the extinction of all living things: “Demolish the house, build a boat!” the god urges. “Abandon riches and seek survival! Spurn property and save life! Put on board the boat the seed of all living creatures!”

The man, his family, and assorted animals wait out the flood in the boat while all other living things perish. Smith presented his translation several weeks later at the Society of Biblical Archaeology to a packed audience that included the prime minister, the archbishop of Canterbury, and many members of the press. “When Smith announced that one of these unappetizing-looking tablets from the barbaric, strange world of the Middle East contained a parallel text to Holy Writ, people were astonished,” says Irving Finkel, a cuneiform expert at the British Museum.

The tablet deciphered by Smith turned out to be the 11th part of the 12-tablet Epic of Gilgamesh and had belonged to the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.), who aspired to gather all known cuneiform writings. Since Smith’s discovery, more than a dozen cuneiform tablets containing some portion of the flood myth have been identified, the earliest of which predate the earliest known versions of the biblical flood text by a thousand years.

Kings

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Royal inscriptions are among the most important sources of ancient Near Eastern history. One of the most intriguing examples is found on the statue of King Idrimi, who ruled Alalakh, a city in present-day Turkey, in the fifteenth century B.C. A lengthy cuneiform inscription sprawls across the statue, spinning a first-person tale of exile, triumph, and redemption.

Royal inscriptions are among the most important sources of ancient Near Eastern history. One of the most intriguing examples is found on the statue of King Idrimi, who ruled Alalakh, a city in present-day Turkey, in the fifteenth century B.C. A lengthy cuneiform inscription sprawls across the statue, spinning a first-person tale of exile, triumph, and redemption.

“In Aleppo, the house of my father,” it begins, “a bad thing occurred, so we fled to the Emarites, my mother’s kin.” Idrimi, a younger son unwilling to play a diminished role, decamps for Canaan, where he finds countrymen who recognize his royal lineage. With their help, he wins over his home city and is proclaimed its rightful ruler by the king of Mitanni, the major regional power. Idrimi then repairs Alalakh’s toppled city wall, conquers more cities, builds a palace, cares for his people, and performs the necessary prayers and sacrifices.

The portion of the inscription that covers Idrimi’s reign is very similar to inscriptions left behind by kings from across the ancient Near East, from Hammurabi of Babylonia (r. 1792–1750 B.C.) to Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria (r. 883–859 B.C.). “The things Idrimi does once he becomes king are the things that Near Eastern kings conventionally claimed to have done in their inscriptions,” says Jacob Lauinger, an Assyriologist at Johns Hopkins University. However, Lauinger adds, the portion covering Idrimi’s exile is more akin to the Old Testament stories of Joseph and David, both younger sons who reach great heights. Just as the inscription’s narrative is a hybrid, so is its language. It is written in Akkadian cuneiform—as was only proper for a royal inscription at the time—but with clear Canaanite influences, such as the placement of verbs at the beginning of clauses.

Although the text reads as if written by Idrimi during his reign, a recent reanalysis of the statue’s stratigraphy suggests it may actually have been written several decades later. As scholars continue to puzzle over this most unusual royal inscription, the wish expressed in its final lines has been fulfilled: “I wrote my service down on my tablet. May one regularly look upon them [the words] so that they [the words] may call blessings on me regularly.”

Medicine

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

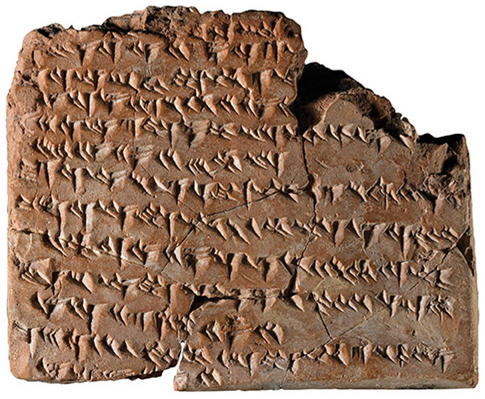

In the ancient Near East, illness was as much a spiritual affliction as a physical one. Demons and ghosts played large roles in diagnosis and treatment, but that’s not to say that the practice of medicine wasn’t codified. One collection of cuneiform texts lists hundreds of medically active substances. And the Late Babylonian diagnostic manual called Sakikku, or “All Diseases,” reveals the careful diagnostic observation of ashipu, or doctor-scholars. The manual, which dates to around the sixth century B.C., consists of 40 tablets, including a treatise on the diagnosis of epilepsy, called miqtu, or “the falling disease.” The writer explains the subtleties of the neurological disease’s presentation in great detail, provides basic prognoses, and ascribes different kinds of seizures to particular malevolent spirits. “[If the epilepsy] demon falls upon him and on a given day he seven times pursues him—[he has been touched by the] hand of the departed spirit of a murderer. He will die.”

In the ancient Near East, illness was as much a spiritual affliction as a physical one. Demons and ghosts played large roles in diagnosis and treatment, but that’s not to say that the practice of medicine wasn’t codified. One collection of cuneiform texts lists hundreds of medically active substances. And the Late Babylonian diagnostic manual called Sakikku, or “All Diseases,” reveals the careful diagnostic observation of ashipu, or doctor-scholars. The manual, which dates to around the sixth century B.C., consists of 40 tablets, including a treatise on the diagnosis of epilepsy, called miqtu, or “the falling disease.” The writer explains the subtleties of the neurological disease’s presentation in great detail, provides basic prognoses, and ascribes different kinds of seizures to particular malevolent spirits. “[If the epilepsy] demon falls upon him and on a given day he seven times pursues him—[he has been touched by the] hand of the departed spirit of a murderer. He will die.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement