From the Trenches

The First Casus Belli

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, April 11, 2016

The massacre took place roughly 10,000 years ago, but the victims’ bones weren’t buried; they lay on the ground at the site of Nataruk near the shore of Kenya’s Lake Turkana. Millennia later, they were discovered entirely by accident. Marta Mirazon-Lahr of the University of Cambridge had planned to explore a sediment layer dating to the time when the first Homo sapiens lived in the area, but her team first found 12 skeletons emerging from the ground due to erosion. Ten of the skeletons show signs of violent deaths: heads had been smashed with clubs, an obsidian arrow tip was embedded in the top of one skull, and another person’s face has a deep cut that may have come from a club inset with obsidian blades. Mirazon-Lahr believes the attack was not the result of a chance encounter between bands of hunters because the wounds were caused by fragile weapons that would have had little use in hunting.

The massacre took place roughly 10,000 years ago, but the victims’ bones weren’t buried; they lay on the ground at the site of Nataruk near the shore of Kenya’s Lake Turkana. Millennia later, they were discovered entirely by accident. Marta Mirazon-Lahr of the University of Cambridge had planned to explore a sediment layer dating to the time when the first Homo sapiens lived in the area, but her team first found 12 skeletons emerging from the ground due to erosion. Ten of the skeletons show signs of violent deaths: heads had been smashed with clubs, an obsidian arrow tip was embedded in the top of one skull, and another person’s face has a deep cut that may have come from a club inset with obsidian blades. Mirazon-Lahr believes the attack was not the result of a chance encounter between bands of hunters because the wounds were caused by fragile weapons that would have had little use in hunting.

Archaeological evidence of prehistoric warfare is hard to find, and mostly comes from much later villages or settlements. This had previously led researchers to believe that sedentism was a prerequisite for organized conflict. What is interesting about the incident at Nataruk is that it appears to have occurred between groups of hunter-gatherers, and the discovery is upending assumptions about what provokes violence between groups of people. According to Mirazon-Lahr, the area around Lake Turkana was an excellent hunting ground 10,000 years ago—a paradise, in effect. The attackers were probably not starving and probably did not go to war as a last resort. Lake Turkana is surrounded by mountains, which might have allowed one group of people to control access to the area near Nataruk. The critical issue was not sedentism, thinks Mirazon-Lahr, but differences in wealth. “In the world of hunter-gatherers,” she says, “wealth is probably defined as access to the best hunting grounds.”

Egypt’s Immigrant Elite

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, April 11, 2016

Two shrines at Gebel el-Silsila on the banks of the Nile River in southern Egypt—thought to have been completely destroyed by an earthquake and erosion—have been discovered largely intact. The shrines, located by a team from Lund University in Sweden led by Maria Nilsson, served as memorials to elite families. One includes statues of a man, his wife, and a son and daughter. Hieroglyphics identify the man as Neferkhewe, the “overseer of foreign lands” under pharaoh Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 B.C.), and his wife as Ruiuresti. “The mother’s name is foreign and the part that we have of the daughter’s name is also foreign,” says John Ward, the project’s associate director. “So it looks as if we have a Nubian family who have taken on the Egyptian religion and produced this shrine in order to gain immortality.”

Two shrines at Gebel el-Silsila on the banks of the Nile River in southern Egypt—thought to have been completely destroyed by an earthquake and erosion—have been discovered largely intact. The shrines, located by a team from Lund University in Sweden led by Maria Nilsson, served as memorials to elite families. One includes statues of a man, his wife, and a son and daughter. Hieroglyphics identify the man as Neferkhewe, the “overseer of foreign lands” under pharaoh Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 B.C.), and his wife as Ruiuresti. “The mother’s name is foreign and the part that we have of the daughter’s name is also foreign,” says John Ward, the project’s associate director. “So it looks as if we have a Nubian family who have taken on the Egyptian religion and produced this shrine in order to gain immortality.”

Medieval River Engineering

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, April 11, 2016

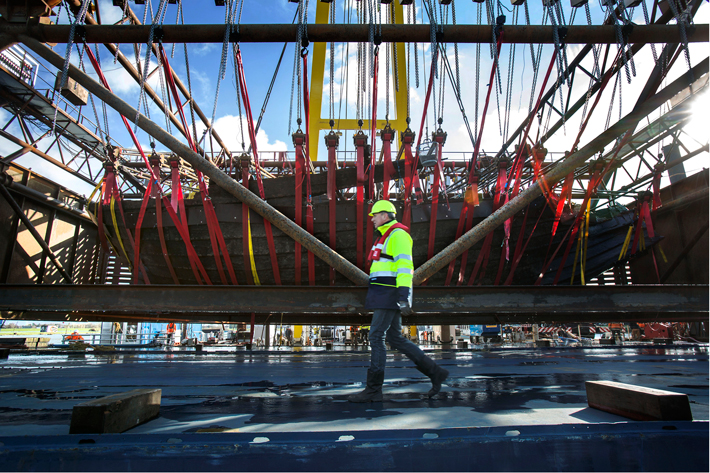

After years of careful planning, archaeologists have raised a well-preserved late medieval ship from the bottom of the IJssel River in the Netherlands. The ship was discovered in a 2012 survey associated with a river-widening project. Archaeologists believe that the ship, an oceangoing trading vessel known as a cog, was intentionally sunk around 600 years ago to help increase water flow on the river. “Today, river works are planned to control the river’s flow,” says Wouter Waldus, the project’s lead maritime archaeologist, “but in the fifteenth century, the problem was too little water flowing.”

After years of careful planning, archaeologists have raised a well-preserved late medieval ship from the bottom of the IJssel River in the Netherlands. The ship was discovered in a 2012 survey associated with a river-widening project. Archaeologists believe that the ship, an oceangoing trading vessel known as a cog, was intentionally sunk around 600 years ago to help increase water flow on the river. “Today, river works are planned to control the river’s flow,” says Wouter Waldus, the project’s lead maritime archaeologist, “but in the fifteenth century, the problem was too little water flowing.”

The 66-foot-long cog rested perpendicular to the river’s flow, along with a barge and a riverboat. Waldus believes engineers of the time would have sunk the boats to block one arm of the river, increasing flow to its other arms. Today, the river’s swift current and heavy boat traffic made raising the boat complicated. The team built a wall to dull the current, used screws to reinforce the ship’s fastening, and constructed an iron cage to protect the ship as it was lifted.

The Death of Joe the Quilter

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, April 11, 2016

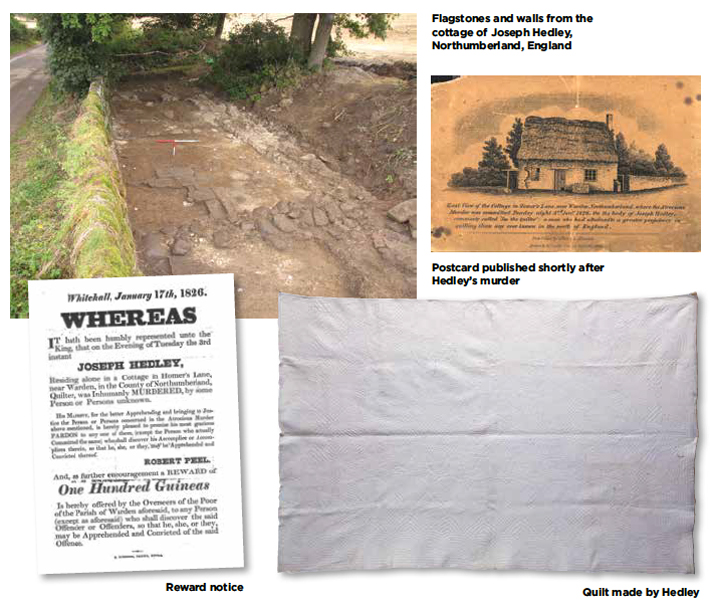

On the evening of January 3, 1826, someone entered the Northumberland home of Joseph Hedley—known locally as “Joe the Quilter” for his great skill with needle and thread—and brutally murdered the lonely old man. Joe’s murder was a sensation that drew even the attention of King George IV, who issued a reward for information leading to the culprit. The reward was never claimed and the crime went unsolved, but Joe was never forgotten. More than 60 years later, a newspaper article was published about his murder, and when archaeologist John Castling of the Living Museum of the North in Beamish began speaking with locals last year, he was surprised to find that people remember the story.

Inspired by an 1826 postcard and using old maps of the area, Castling and his team began to look for Joe’s cottage. On a piece of unfarmed land, they identified pottery dating to Joe’s time and mortar associated with a building. Castling excavated the site for four weeks and uncovered 10 tons of material: stones from walls, flagstones, fireplace bricks, buttons, and pins made of bone—and lead weights possibly associated with quilting. “We were lucky because the house is so isolated, no other buildings were ever built there, and it wasn’t destroyed until 1872,” he says. Plans are now under way to reconstruct Joe’s cottage. “It’s so rare to find anything related to an individual, and especially so because Joe and those who knew him weren’t wealthy or particularly famous,” says Castling. “It’s a real insight into the life and home of a genuinely ordinary man only made famous by his extraordinary death.”

Vikings, Worms, and Emphysema

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, April 11, 2016

The woeful state of Viking bathrooms could be a factor behind smokers’ coughs in Scandinavia. Sometimes in human evolution, populations adapt in ways that aren’t always beneficial in the long run. For example, the sickle-cell trait evolved in humans because it provides some protection against malaria, but people who inherit the trait from both parents develop sickle-cell disease, a serious blood disorder. In this new case, molecular biologists have connected intestinal parasites in the Viking Age to modern lung disease.

The woeful state of Viking bathrooms could be a factor behind smokers’ coughs in Scandinavia. Sometimes in human evolution, populations adapt in ways that aren’t always beneficial in the long run. For example, the sickle-cell trait evolved in humans because it provides some protection against malaria, but people who inherit the trait from both parents develop sickle-cell disease, a serious blood disorder. In this new case, molecular biologists have connected intestinal parasites in the Viking Age to modern lung disease.

Last year, Danish scientists studying the remains of a Viking privy found that the ancient Norse and their domestic animals were infested with a variety of intestinal parasites. These parasites release enzymes called proteases that cause disease. The immune system also creates proteases that can cause inflammation and damage, but the body has natural defenses against those, including a molecule called alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT). Because they were more or less constantly infected, Vikings evolved to produce “deviant” forms of A1AT that were specifically useful against worm-related proteases instead of the body’s own. In the absence of normal A1AT, the immune system’s own proteases are free to damage tissue, including in the lungs and liver. At the time, the benefits of this genetic mutation outweighed the risks. Not so today.

Today, this deficiency of normal A1AT is the only known genetic risk factor for lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema. People also live longer and smoke tobacco, which allows the damage caused by the deficiency to accumulate. “It is only in the last century that modern medicine has allowed human populations to be treated for disease-causing worms,” says Richard J. Pleass of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. “Consequently, these deviant forms of A1AT that once protected people from parasites are now at liberty to cause emphysema and COPD.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Dressing for the Ages

Off the Grid

Let a Turtle Be Your Psychopomp

The Price of Tea in China

What Happened After 1492?

Women in a Temple of Death

Islam North of the Pyrenees

Mesolithic Markings

Vikings, Worms, and Emphysema

Medieval River Engineering

The Death of Joe the Quilter

Egypt’s Immigrant Elite

The First Casus Belli

Artifact

The Wild Man of the medieval world

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement