Features

Franklin’s Last Voyage

By ALLAN WOODS

Monday, June 27, 2016

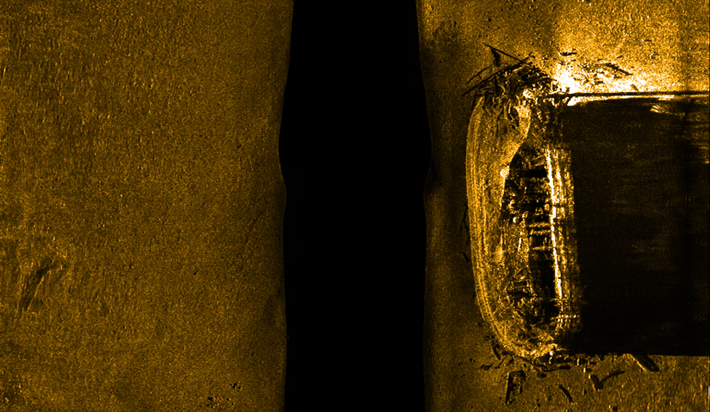

Aboard the Canadian Coast Guard ship Sir Wilfrid Laurier, a team of marine and terrestrial archaeologists, hydrographers, the ship’s captain, and a helicopter pilot gathered to finalize the day’s plan. It was September 1, 2014, and they were in the waters of the Canadian territory of Nunavut, searching the west coast of King William Island and the eastern part of Queen Maud Gulf—some 540 square miles of sea. The team, led by Ryan Harris, a senior underwater archaeologist with Parks Canada, had been looking since 2008 for signs of perhaps the two most famous ships lost in the search for the Northwest Passage: the reinforced British bomb vessels HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, led by Sir John Franklin and missing since the late 1840s.

Scott Youngblut, a Canadian government hydrographer, was heading out from Laurier on a helicopter to a small, uninhabited island off the western edge of Nunavut’s Adelaide Peninsula to set up a GPS station that would help him chart the local waters. The area being searched is near where, in the nineteenth century, an Inuit elder had reported rummaging through an abandoned ship. Alongside Youngblut were Doug Stenton, Nunavut’s director of heritage, and Robert Park, an archaeological anthropologist from the University of Waterloo, who had come along to survey the island. Before landing, Stenton noted two promising signs: the absence of polar bears, and the presence of what appeared to be clear cultural features, including tent rings and small stone mounds indicative of supply caches. After just 20 minutes on the ground, helicopter pilot Andrew Stirling called Stenton over. Before them was a 17-inch, U-shaped iron fitting partially embedded in sand.

Stenton was intrigued by the find. It was different and more substantial than other items thought to have come from Franklin’s ships, such as nails and spikes. Those artifacts had been discovered on or around King William Island, to the northeast. Stenton picked up the 12-pound piece of iron to look for the telltale broad arrow that would identify it as property of the British Royal Navy, which had commissioned and outfitted Franklin’s expedition. “When I opened my hand I saw the number 12—and a broad arrow—stamped into the bottom,” Stenton recalls.

Stenton was intrigued by the find. It was different and more substantial than other items thought to have come from Franklin’s ships, such as nails and spikes. Those artifacts had been discovered on or around King William Island, to the northeast. Stenton picked up the 12-pound piece of iron to look for the telltale broad arrow that would identify it as property of the British Royal Navy, which had commissioned and outfitted Franklin’s expedition. “When I opened my hand I saw the number 12—and a broad arrow—stamped into the bottom,” Stenton recalls.

That evening on Laurier, Stenton, Harris, and the Parks Canada crew examined the find, as well as two wooden disks they had discovered. Because of the iron fitting’s size, they guessed it had come from Erebus or Terror, and not from one of the smaller boats Franklin’s crew is known to have used after their ships had become icebound. Harris concluded that the iron was most likely part of a boat-launching mechanism called a davit pintle, and that the disks were possibly plugs for a deck hawse, an opening through which a ship’s anchor chain passes into a storage space below the deck.

|

Slideshow:

|

Remains of an Arctic Shipwreck

|

Rites of the Scythians

By ANDREW CURRY

Monday, June 13, 2016

Russian archaeologist Andrey Belinski wasn’t sure what to expect when he found himself facing a small mound in a farmer’s field at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains. To the untrained eye, the 12-foot feature looked like little more than a hillock. To Belinski, who was charged with excavating the area to make way for new power lines, it looked like a type of ancient burial mound called a kurgan. He considered the job of excavating and analyzing the kurgan, which might be damaged by the construction work, fairly routine. “Basically, we planned to dig so we could understand how it was built,” Belinski says. As he and his team began to slice into the mound, located 30 miles east of Stavropol, it became apparent that they weren’t the first people to take an interest. In fact, looters had long ago ravaged some sections. “The central part was destroyed, probably in the nineteenth century,” Belinski says. Hopes of finding a burial chamber or artifacts inside began to fade.

It took nearly a month of digging to reach the bottom. There, Belinski ran into a layer of thick clay that, at first glance, looked like a natural feature of the landscape, not the result of human activity. He uncovered a stone box, a foot or so deep, containing a few finger and rib bones from a teenager. But that wasn’t all. Nested one inside the other in the box were two gold vessels of unsurpassed workmanship. Beneath these lay three gold armbands, a heavy ring, and three smaller bell-shaped gold cups. “It was a huge surprise for us,” Belinski says. “Somehow, the people who plundered the rest didn’t locate these artifacts.”

As he continued to excavate the area surrounding the kurgan, he spotted postholes near the stone box, as though tree trunks had once been sunk in the earth to support a pavilion or roof. Belinski and Anton Gass of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in Berlin, whom Belinski had invited to participate in the excavation, realized that they had found something far beyond a simple burial mound. In fact, some scholars think the site may have been the location of an intense ritual and subsequent burial rite performed by some of the ancient world’s most fearsome warriors.

From about 900 to 100 B.C., nomadic tribes dominated the steppes and grasslands of Eurasia, from what is today western China all the way east to the Danube. All across this vast expanse, archaeological evidence shows that people shared core cultural practices. “They were all nomads, they were heavily socially stratified, they had monumental burial structures and rich grave goods,” says Hermann Parzinger, head of Berlin’s Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation and former head of the German Archaeological Institute. Today, archaeologists refer to the members of this interconnected world as Scythians, a name used by the Greek historian Herodotus.

|

Slideshow:

|

Inside a Scythian Burial Mound

|

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Is it Esmeralda?

Off the Grid

New Dates for the Oldest Cave Paintings

Fact-Checking Lawrence of Arabia

Etruscan Code Uncracked

Naval Mystery Solved

Off with Their Heads

Cursing the Competition

Proof in the Prints

Fit for a War God

A Life Story

A Villa under the Garden

Iceland’s Young Migrant

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

More evidence of the survivors was eventually uncovered, much of it grisly. Later expeditions found buried or mutilated human remains—some alone, some in groups of several dozen. It is not known if starving crew members resorted to cannibalism, or whether the condition of the remains was caused by wild animals. Other traces included iron nails, metal cutlery, tools, knives, and wood fragments that the crew carried with them on their doomed march. But just as important, or more, are the oral histories and eyewitness accounts, collected by later search parties, of the Inuit, who traveled seasonally through the area for centuries.

More evidence of the survivors was eventually uncovered, much of it grisly. Later expeditions found buried or mutilated human remains—some alone, some in groups of several dozen. It is not known if starving crew members resorted to cannibalism, or whether the condition of the remains was caused by wild animals. Other traces included iron nails, metal cutlery, tools, knives, and wood fragments that the crew carried with them on their doomed march. But just as important, or more, are the oral histories and eyewitness accounts, collected by later search parties, of the Inuit, who traveled seasonally through the area for centuries.

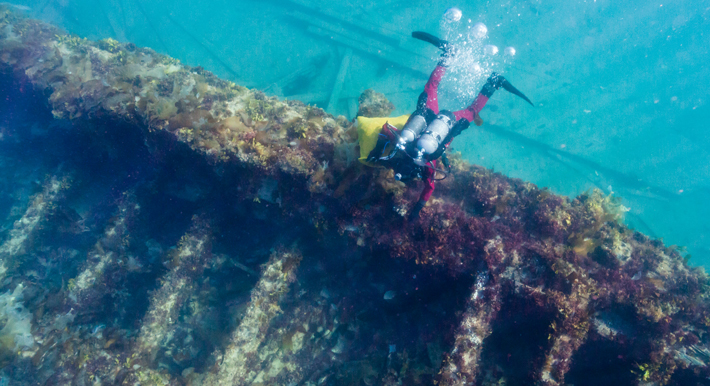

Harris and Moore had to wait through the announcement, a day of rest, and a major storm—a reminder of the dangerous power of the Arctic—before they could don dry suits and investigate their prize, which sits upright in just 30 feet of water. “The visibility was so bad [because of the storm] that we couldn’t see the wreck when we got to the bottom,” Moore says.

Harris and Moore had to wait through the announcement, a day of rest, and a major storm—a reminder of the dangerous power of the Arctic—before they could don dry suits and investigate their prize, which sits upright in just 30 feet of water. “The visibility was so bad [because of the storm] that we couldn’t see the wreck when we got to the bottom,” Moore says.

Although the Scythians were united by their nomadic, horse-centered lifestyle, historians and archaeologists do not think they were ever a single political entity. Based on regional differences in their art, artifacts, and burial practices, scholars posit that they were, rather, a collection of tribes who spoke related languages and had a broadly shared artistic and material culture. They had no written language and their nomadic lifestyle has left relatively little in terms of settlements for archaeologists to uncover. Thus, modern scholars have had to rely heavily on the accounts of ancient historians to interpret the archaeological evidence. “Archaeological finds are, by their nature, mute,” says Askold Ivantchik, director of the Centre for Comparative Studies of Ancient Civilizations at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. “The main source we have is texts from other cultures, primarily the Greeks and Romans.”

Although the Scythians were united by their nomadic, horse-centered lifestyle, historians and archaeologists do not think they were ever a single political entity. Based on regional differences in their art, artifacts, and burial practices, scholars posit that they were, rather, a collection of tribes who spoke related languages and had a broadly shared artistic and material culture. They had no written language and their nomadic lifestyle has left relatively little in terms of settlements for archaeologists to uncover. Thus, modern scholars have had to rely heavily on the accounts of ancient historians to interpret the archaeological evidence. “Archaeological finds are, by their nature, mute,” says Askold Ivantchik, director of the Centre for Comparative Studies of Ancient Civilizations at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. “The main source we have is texts from other cultures, primarily the Greeks and Romans.”

Appealing as the literary and historical parallels might be, according to Ivantchik, the Greek artisans who likely made the vessels were probably thinking in more symbolic terms. “It’s very rare to see representations of historical events in Greek art,” he says. “The imagery on the vessels is very interesting and important, but interpretation is a delicate problem.” Belinski agrees, and considers Gass’ theory a stretch. “Why would this not particularly sacred saga be on sacred vessels?” he asks. Instead, he posits that the old man slaying a younger warrior is more likely a metaphor, or a depiction of an unknown ritual. “Until we find written sources, we can’t say for sure,” he adds.

Appealing as the literary and historical parallels might be, according to Ivantchik, the Greek artisans who likely made the vessels were probably thinking in more symbolic terms. “It’s very rare to see representations of historical events in Greek art,” he says. “The imagery on the vessels is very interesting and important, but interpretation is a delicate problem.” Belinski agrees, and considers Gass’ theory a stretch. “Why would this not particularly sacred saga be on sacred vessels?” he asks. Instead, he posits that the old man slaying a younger warrior is more likely a metaphor, or a depiction of an unknown ritual. “Until we find written sources, we can’t say for sure,” he adds.

The golden vessels, the human remains—which, for now at least, archaeologists are interpreting as a human sacrifice rather than a full burial—and the remains of a substantial construction perched on top of the mound are likely indications that this was some sort of altar or ritual spot, and had once probably been used for an important ceremony, perhaps of the kind Herodotus describes. “There could have been some type of a roof construction, and there may have been hanging banners or standards with flags as well,” says Gass. “We’re not sure, but there was something major there.” After the ritual, the kurgan was built on top. Since most kurgans are clearly tombs, archaeologists say there are few parallels for a construction like this. Parzinger suggests that empty kurgans were rarely reported or written about in the past, and might be more common than once thought. Gass and Belinski think the Sengileevskoe-2 kurgan was a cenotaph, a symbolic burial built to mark some tremendous upheaval in the Scythian world, perhaps the death of a king who was buried elsewhere. “Something important happened,” Gass says. “But what?”

The golden vessels, the human remains—which, for now at least, archaeologists are interpreting as a human sacrifice rather than a full burial—and the remains of a substantial construction perched on top of the mound are likely indications that this was some sort of altar or ritual spot, and had once probably been used for an important ceremony, perhaps of the kind Herodotus describes. “There could have been some type of a roof construction, and there may have been hanging banners or standards with flags as well,” says Gass. “We’re not sure, but there was something major there.” After the ritual, the kurgan was built on top. Since most kurgans are clearly tombs, archaeologists say there are few parallels for a construction like this. Parzinger suggests that empty kurgans were rarely reported or written about in the past, and might be more common than once thought. Gass and Belinski think the Sengileevskoe-2 kurgan was a cenotaph, a symbolic burial built to mark some tremendous upheaval in the Scythian world, perhaps the death of a king who was buried elsewhere. “Something important happened,” Gass says. “But what?”