From the Trenches

Mask Metamorphosis

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, August 15, 2016

Just as the details of a spectacular first- to third-century A.D. bronze mask have emerged after more than a year of conservation, so has the true nature of a newly excavated area of the important ancient city of Hippos-Sussita in Israel begun to take shape. The mask is almost 12 inches tall and 11 inches wide, and weighs more than 11 pounds. Because the artifact is unique—it is the only large bronze mask depicting the wild, rustic demigod Pan to have been found in Israel—conservators decided to clean half by hand, then assess it before continuing with the rest.

More recently, the Hippos-Sussita team, led by Michael Eisenberg of the University of Haifa, has uncovered a large basalt propylaeum, or gateway, which he can now connect with the tower in which the mask was found. “At first the mask seemed like it was almost a random find, having been discovered some 60 feet away from the complex we were digging in,” says Eisenberg, “but now I am starting to realize that it’s connected to that area and supports one of the leading assumptions we have—that we are actually excavating a sanctuary dedicated to the god Dionysus or to Pan, who was part of his retinue.”

More recently, the Hippos-Sussita team, led by Michael Eisenberg of the University of Haifa, has uncovered a large basalt propylaeum, or gateway, which he can now connect with the tower in which the mask was found. “At first the mask seemed like it was almost a random find, having been discovered some 60 feet away from the complex we were digging in,” says Eisenberg, “but now I am starting to realize that it’s connected to that area and supports one of the leading assumptions we have—that we are actually excavating a sanctuary dedicated to the god Dionysus or to Pan, who was part of his retinue.”

The City That Wasn’t

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, August 15, 2016

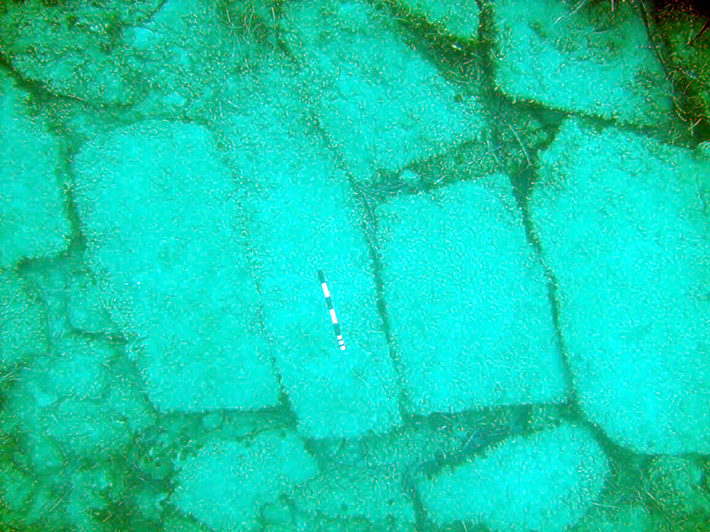

Formations discovered in shallow water off the coast of the island of Zakynthos in the Ionian Sea were initially thought to be the remains of an ancient Greek city. However, there is a puzzling absence of artifacts such as ceramic sherds among what appear to be columns and paving stones to indicate that people had ever actually lived there. Now researchers have subjected these “structures” to a range of tests, and found that they are indeed extremely old, but they certainly weren’t made by the ancient Greeks.

Formations discovered in shallow water off the coast of the island of Zakynthos in the Ionian Sea were initially thought to be the remains of an ancient Greek city. However, there is a puzzling absence of artifacts such as ceramic sherds among what appear to be columns and paving stones to indicate that people had ever actually lived there. Now researchers have subjected these “structures” to a range of tests, and found that they are indeed extremely old, but they certainly weren’t made by the ancient Greeks.

“The first few photographs I saw really did look as if they might be columns and paving slabs,” says Julian Andrews, an environmental scientist at the University of East Anglia, “but as I saw more images, it was clear they probably weren’t.”

Based on carbon isotope analysis of a sample of the formations, Andrews and his colleagues determined that they were formed by microbes that use hydrocarbons seeping through the seafloor, most likely methane, as nourishment. These bacteria lived around 16 feet below the seafloor at the time, in an oxygen-free environment. Their waste helped transform the sediment around the seeps into a natural cement-like substance known as dolomite. In the years since, the sediment eroded away, exposing the formations.

Analysis of strontium isotopes in the sample helped the researchers determine when they were created. “We can be reasonably confident they’re no older than the Pliocene Epoch,” says Andrews, “so they’re probably no older than four million years.”

Culture Clash

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, August 15, 2016

In northeastern France’s Alsace region, a team from the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research has discovered graphic evidence for a violent Neolithic-era clash of cultures. While digging in a fortified village dating to between 4400 and 4200 B.C., archaeologists unearthed a storage pit that held the mutilated remains of five men and one teenage boy, as well as four severed left arms. Archaeologist Philippe Lefranc suggests the limbs were battlefield trophies, and that the skeletons belonged to members of a captured enemy war party. “I think we are seeing ritualized violence against captives who were initially alive,” says Lefranc. “It probably took place in the middle of the village during a victory celebration. All the remains were eventually thrown in a ritual refuse dump.” Lefranc thinks the enemy warriors were from a new population migrating into the area from the Paris Basin to the west. Despite losing this round, they eventually triumphed. At the end of the fifth millennium, the local pottery style and burial rituals were replaced by those of the newcomers, and all the old villages in Alsace were relocated.

In northeastern France’s Alsace region, a team from the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research has discovered graphic evidence for a violent Neolithic-era clash of cultures. While digging in a fortified village dating to between 4400 and 4200 B.C., archaeologists unearthed a storage pit that held the mutilated remains of five men and one teenage boy, as well as four severed left arms. Archaeologist Philippe Lefranc suggests the limbs were battlefield trophies, and that the skeletons belonged to members of a captured enemy war party. “I think we are seeing ritualized violence against captives who were initially alive,” says Lefranc. “It probably took place in the middle of the village during a victory celebration. All the remains were eventually thrown in a ritual refuse dump.” Lefranc thinks the enemy warriors were from a new population migrating into the area from the Paris Basin to the west. Despite losing this round, they eventually triumphed. At the end of the fifth millennium, the local pottery style and burial rituals were replaced by those of the newcomers, and all the old villages in Alsace were relocated.

Lost and Found (Again)

Monday, August 15, 2016

In 1838, a cache of silver was found at Ley Farm in Aberdeenshire in northeast Scotland. While what came to be known as the Gaulcross Hoard might have originally contained more artifacts, only three pieces are known today from the original discovery. Almost 200 years later, archaeologists have gone back to the site and unearthed no less than 100 new silver artifacts from the hoard, including ingots, a crescent-shaped pendant, and a zoomorphic brooch, along with other jewelry fragments.

Some of the most interesting objects are what is termed hacksilver—plates, spoons, belt fittings, bracelets, and even coins that were deliberately broken, cut, or bent before being used as currency or melted down for reuse. “Our work is the first to acknowledge the existence of hacksilver extending beyond the Roman period and into the fifth and sixth centuries A.D. in Scotland,” says Alice Blackwell, who is studying the hoard as part of the National Museum of Scotland’s Glenmorangie Research Project. “It has long been apparent that silver was the main material used in early medieval Scotland to show wealth and power, but what we have lacked until now is any real understanding of how this most precious resource was managed.”

A True Viking Saga

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, August 15, 2016

A skeleton found at the bottom of an abandoned well in Trondheim, Norway, seems to confirm a tale of defeat and destruction told in an ancient Norse saga. In 1197, a faction of the Norwegian aristocracy known as the Baglers attacked Sverresborg, the castle stronghold of the Viking king Sverre. The story of the siege—including the “killing” of the castle’s well by throwing the dead body of one of the king’s men into it—is well known, but its veracity has been questioned. “Sverre’s saga has very detailed descriptions of the battles between the king and his main enemy, and it’s also rich in references to places and people,” says lead archaeologist Anna Petersén of the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research. “The human remains in the well indicate that the saga is trustworthy. The proven relationship to events described in Norwegian history makes this discovery unique, and a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

A skeleton found at the bottom of an abandoned well in Trondheim, Norway, seems to confirm a tale of defeat and destruction told in an ancient Norse saga. In 1197, a faction of the Norwegian aristocracy known as the Baglers attacked Sverresborg, the castle stronghold of the Viking king Sverre. The story of the siege—including the “killing” of the castle’s well by throwing the dead body of one of the king’s men into it—is well known, but its veracity has been questioned. “Sverre’s saga has very detailed descriptions of the battles between the king and his main enemy, and it’s also rich in references to places and people,” says lead archaeologist Anna Petersén of the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research. “The human remains in the well indicate that the saga is trustworthy. The proven relationship to events described in Norwegian history makes this discovery unique, and a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

A New View of the Birthplace of the Olympics

Romans on the Bay of Naples

Worlds Within Us

Letter from Rotterdam

From the Trenches

Piecing Together a Plan of Ancient Rome

Off the Grid

Gimme Middle Paleolithic Shelter

Zapotec Power Rites

Mystery Buildings at Petra

Sun and Moon

The Great Parallelogram

The Prisoners of Richmond Castle

A True Viking Saga

Culture Clash

Lost and Found (Again)

The City That Wasn’t

Mask Metamorphosis

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement