Features

Expanding the Story

By SARA TOTH STUB

Tuesday, November 01, 2016

In 1935, Dmitri Baramki, a young archaeologist working for the British administration in his native Palestine, began excavating three dirt mounds outside the ancient city of Jericho 25 miles east of Jerusalem. Baramki was concerned that important evidence of a Byzantine church or monastery inside the mounds was being destroyed by the locals’ habit of pilfering and reusing the ancient stones for building material. However, he soon realized that what he had found was not a Christian religious building at all, but instead, the remains of an eighth-century Islamic palace.

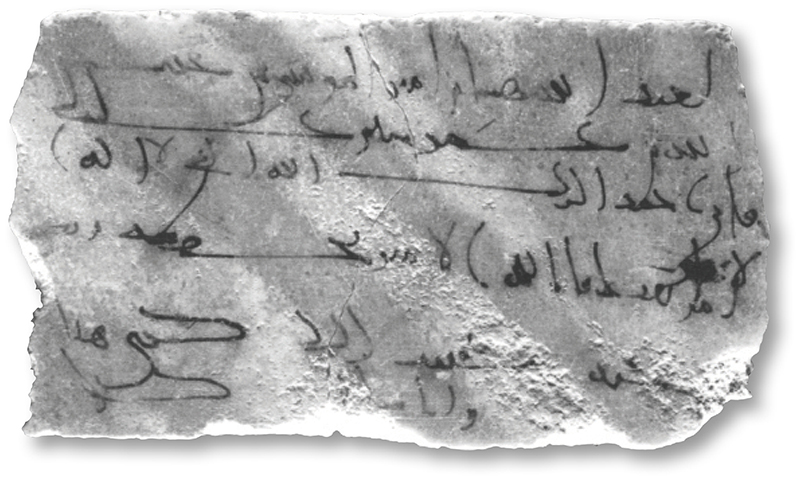

Though much of the palace complex was in shambles, likely destroyed by an earthquake in A.D. 747, Baramki’s team nevertheless unearthed detailed mosaics and stuccowork of the highest quality that once had decorated the palace’s walls and floors. Baramki also discovered a white marble ostracon inscribed in ink in Arabic reading “Hisham, commander of the faithful.” The phrase is probably the opening of a letter, and is the only writing found at the site. Local residents, who had previously called the mounds Khirbet al-Mafjar, “Ruins of Flowing Water,” for their location near an aqueduct, began referring to them as “Hisham’s Palace.” Soon archaeologists concluded that the palace had been built during the reign of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, the tenth Umayyad caliph (r. A.D. 724-743), Islam’s chief religious and political leader.

The Umayyads were a merchant family from Syria who converted to Islam in 627. Islam’s founder, Muhammad, died in 632 without leaving a clear system of succession, ushering in a period of strife. By 661 the Umayyads had ascended to the caliphate, having won the first of many wars fought for leadership of the religion and its growing sphere of influence. The first Umayyad caliph, Muawiyah ibn Abi Sufyan, moved the caliphate’s capital from Medina, in what is now Saudi Arabia, to Damascus, in modern-day Syria, where the family already had high standing, thereby boosting the power and legitimacy of the new leader. For 89 years the Umayyads reigned over an empire stretching from India to Spain. Their fragile hold on power was constantly threatened by various groups claiming rights to the caliphate, and they ultimately lost several key military battles to the Abbasid Dynasty, who finally wrested away control in 750.

Robert W. Hamilton was the head of the British Mandate for Palestine’s Department of Antiquities who oversaw Baramki’s excavations at Khirbet al-Mafjar and eventually joined him at the dig in the later 1940s. The sumptuous nature of the palace, much more extensively decorated than other Umayyad desert compounds found across the Middle East, could, thought Hamilton, only be fully explained by linking it to one particular short-lived caliph—a nephew of Hisham named Walid ibn Yazid, known from later Islamic writers for his love of music, wine, and women. “It existed for reasons which must be sought not in the realm of public affairs but in that of personal pleasure,” Hamilton wrote in his 1959 book, Khirbat al-Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordan Valley. In another book, Walid and His Friends, Hamilton relates a story from the tenth-century text of Islamic historian Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani about Walid bathing in a tub of wine, and then emerging intoxicated with the level of wine in the tub significantly lowered. Al-Isfahani does not mention where this episode took place, but Hamilton writes that it occurred in the palace’s bathhouse.

|

Sidebar:

|

The Palace’s Other Lives

|

Samhain Revival

By ERIN MULLALLY

Monday, October 17, 2016

It is the night of October 31, and hundreds of people have gathered at the Hill of Ward, once known as Tlachtga, in County Meath, Ireland. Some wear robes and masks and carry torches and banners emblazoned with spiritual symbols. It is all part of a revival of the ancient Celtic festival called Samhain (pronounced “SAH-win”) that includes processions, chanting, and storytelling. “Let’s raise our voices together and call back Tlachtga from the mist of time,” proclaims Deborah Snowwolf Conlon, one of the festival’s organizers. It is a contemporary celebration repeated annually, of a piece with countless other seasonal celebrations across the world that have roots both modern and ancient. In this case, neither the choice of site nor date is incidental: The Hill of Ward was one of the main spiritual centers for the ancient Celts, and Samhain was first celebrated at the same time of year millennia ago. New archaeological work is looking closely at the history of the Hill of Ward, which until recently had been overlooked in Ireland’s archaeologically rich Boyne Valley. Researchers are hoping to discover how its use and value evolved over the centuries—along with the traditional rites and celebrations that eventually led to the modern festival of Halloween.

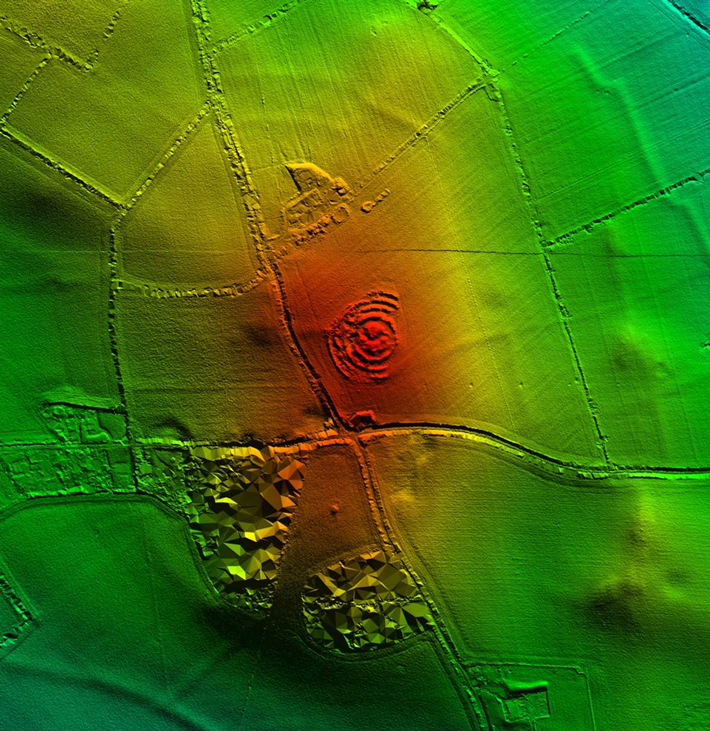

Only 30 miles north of Dublin, the Boyne Valley is the location of one of the world’s most important arrays of prehistoric sites. It includes the well-known “passage tombs” of Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth, which at around 5,500 years old predate even the pyramids of Egypt. The Hill of Tara, the traditional seat of the ancient High Kings of Ireland, is also nearby. Among them sits the relatively modest Hill of Ward, on privately owned farmland, with striking views across the valley. The site today consists of four concentric earthworks that enclose an area roughly 500 feet in diameter, with some of the banks either partially or completely destroyed. Though some archaeological survey work was done at the Hill of Ward in the 1930s, the site was virtually untouched until summer 2014, when a team led by Stephen Davis of University College Dublin began excavations.

Using lidar and geophysical tools, Davis and his team have determined that the Hill of Ward was built in three distinct phases over many centuries. The first phase was constructed during the Bronze Age (1200–800 B.C.), while the last dates to the late Iron Age, around the time of Ireland’s conversion to Christianity (A.D. 400–520). “The middle phase, or physical center, of the monument, which itself was built in multiple stages,” explains Davis, “is proving the most mysterious.” Much of the excavation work done to date at the Hill of Ward has focused on this middle phase, which is providing tantalizing clues into the ritual roles it may have played throughout the centuries.

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Piltdown’s Lone Forger

Off the Grid

Codex Subtext

The Rabbit Farms of Teotihuacán

Murder on the Mountain?

Breaking Cahokia’s Glass Ceiling

Evolve and Catch Fire

Coast over Corridor

Ötzi’s Sartorial Splendor

And They’re Off!

The Blood of the King

China’s Legendary Flood

Shifting Sands

Man Meets Dog, Both Meet Death

World Roundup

Maya victory monument, Neanderthal cannibals, Paleolithic smorgasbord, King Tut’s meteor dagger, and Melanesian tattooing

Artifact

A Cambridge don’s magic shoe

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Scholars today are quick to point out Hamilton’s colonial motivations, saying he, like many Europeans at the time, viewed Islamic culture as a mix of the backward and the exotic. Aside from a few late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century explorers, European powers had only entered the Middle East recently, at the end of World War I, establishing colonial mandates that lasted through World War II in what are now Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and other countries. The same scholars also note that the Islamic historians Hamilton relies on are widely viewed as biased against the Umayyads because they were writing under the Abbasid Caliphate, and had an interest in portraying its predecessors as corrupt and impious in order to promote Abbasid legitimacy. “Hamilton’s writings have cast this particular monument in a very superficial role in Islamic architecture,” says Donald Whitcomb, a University of Chicago archaeologist who, along with the Palestinian Authority’s Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, is now leading the Jericho Mafjar Project. “I don’t deny that the Umayyads had some good parties, but I don’t think it was the purpose of the site.”

Scholars today are quick to point out Hamilton’s colonial motivations, saying he, like many Europeans at the time, viewed Islamic culture as a mix of the backward and the exotic. Aside from a few late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century explorers, European powers had only entered the Middle East recently, at the end of World War I, establishing colonial mandates that lasted through World War II in what are now Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and other countries. The same scholars also note that the Islamic historians Hamilton relies on are widely viewed as biased against the Umayyads because they were writing under the Abbasid Caliphate, and had an interest in portraying its predecessors as corrupt and impious in order to promote Abbasid legitimacy. “Hamilton’s writings have cast this particular monument in a very superficial role in Islamic architecture,” says Donald Whitcomb, a University of Chicago archaeologist who, along with the Palestinian Authority’s Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, is now leading the Jericho Mafjar Project. “I don’t deny that the Umayyads had some good parties, but I don’t think it was the purpose of the site.” During Baramki’s and Hamilton’s original excavations, which covered more than 3.5 acres, they unearthed the remains of an impressive complex composed of a palace, bathhouse, courtyard, and mosque, all surrounded by defensive walls. The palace’s interior walls and ceilings are covered in extravagantly carved stucco in whimsical patterns, along with human and animal figures. Much of the imagery is derived from both the Greek and pre-Islamic Persian Sasanian Empires. Brick vaulting echoes building techniques from ancient Iraq. The floor plan of the palace, consisting of rooms arranged around a central courtyard, is reminiscent of those of the Romans. “There is no doubt there is something about this architecture that is an inheritance from pre-Islamic tradition,” says Katia Cytryn-Silverman, a Hebrew University of Jerusalem expert in Islamic archaeology.

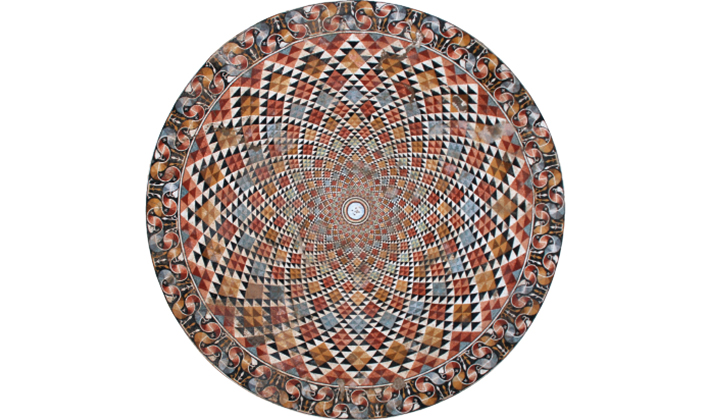

During Baramki’s and Hamilton’s original excavations, which covered more than 3.5 acres, they unearthed the remains of an impressive complex composed of a palace, bathhouse, courtyard, and mosque, all surrounded by defensive walls. The palace’s interior walls and ceilings are covered in extravagantly carved stucco in whimsical patterns, along with human and animal figures. Much of the imagery is derived from both the Greek and pre-Islamic Persian Sasanian Empires. Brick vaulting echoes building techniques from ancient Iraq. The floor plan of the palace, consisting of rooms arranged around a central courtyard, is reminiscent of those of the Romans. “There is no doubt there is something about this architecture that is an inheritance from pre-Islamic tradition,” says Katia Cytryn-Silverman, a Hebrew University of Jerusalem expert in Islamic archaeology. Baramki and Hamilton also uncovered an expansive polychrome mosaic floor measuring nearly 9,000 square feet, making it one of the largest intact mosaics found in this part of the world. The geometric patterns and borders on the mosaic lend it the look of a carpet lining the floor, and, in fact, some tesserae are laid out to look like tassels at the edges of a rug. One alcove in the bathhouse contains a mosaic known as the “Tree of Life,” which depicts two peaceful gazelles separated by a tree from a lion attacking another gazelle. The arrangement has been widely interpreted by Islamic art historians as an Umayyad expression of their desire for political and cultural power, using imagery dating back to ancient Persia and Mesopotamia, where the lion represented royalty. Depictions of lions attacking other animals dating from the Byzantine age have also been uncovered in Jordan and Syria, and the Umayyads would have been familiar with these as well. “The lion often represents power, and this scene is inspired by illustrations from other sites,” says Mahmoud Hawari, an archaeologist and research associate at Oxford’s Khalili Research Centre for the Art and Material Culture of the Middle East, who has studied Khirbet al-Mafjar and other desert castles. Hawari believes that the scene also symbolizes the battle of good versus evil. “The composition of the scene is quite unusual, reflecting how the Umayyads were a hybrid of several civilizations, and we see this in their culture, their art, their way of life.”

Baramki and Hamilton also uncovered an expansive polychrome mosaic floor measuring nearly 9,000 square feet, making it one of the largest intact mosaics found in this part of the world. The geometric patterns and borders on the mosaic lend it the look of a carpet lining the floor, and, in fact, some tesserae are laid out to look like tassels at the edges of a rug. One alcove in the bathhouse contains a mosaic known as the “Tree of Life,” which depicts two peaceful gazelles separated by a tree from a lion attacking another gazelle. The arrangement has been widely interpreted by Islamic art historians as an Umayyad expression of their desire for political and cultural power, using imagery dating back to ancient Persia and Mesopotamia, where the lion represented royalty. Depictions of lions attacking other animals dating from the Byzantine age have also been uncovered in Jordan and Syria, and the Umayyads would have been familiar with these as well. “The lion often represents power, and this scene is inspired by illustrations from other sites,” says Mahmoud Hawari, an archaeologist and research associate at Oxford’s Khalili Research Centre for the Art and Material Culture of the Middle East, who has studied Khirbet al-Mafjar and other desert castles. Hawari believes that the scene also symbolizes the battle of good versus evil. “The composition of the scene is quite unusual, reflecting how the Umayyads were a hybrid of several civilizations, and we see this in their culture, their art, their way of life.”

Work at Khirbet al-Mafjar also has much to say about the impression that customs and mores change immediately upon the introduction of a new culture through conquest. The wine press challenges that idea. Jennings calls the press the most elaborate and well-constructed example in the entire region. It had a brick roof, white mosaic floor, and crushing machinery, and was housed in a building made from the same local ashlar sandstone masonry as the palace and bathhouse. He acknowledges that the site, with its wine press and nude statuary, doesn’t always square with ideas people have about the history of Islam. Instead, scholars have demonstrated that Islam’s ban on alcohol and human imagery only gained traction later and has varied in its stringency by place and time. “It just shows that cultural change doesn’t happen the same moment political change does,” Hawari says. “Wine was part and parcel of Umayyad culture and we even see this reflected in their poetry and songs. People don’t switch their habits overnight.” Hamdan Taha, a former director of the Palestinian Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, concurs, explaining that the wine press, along with the art from the site, is further evidence of how the Umayyads, even while introducing a new religion into the region, still clung to existing cultural practices. “The material at Khirbet al-Mafjar shows that the Umayyads didn’t see any contradiction between their art and their religion,” Taha says, “and understood how they could coexist.”

Work at Khirbet al-Mafjar also has much to say about the impression that customs and mores change immediately upon the introduction of a new culture through conquest. The wine press challenges that idea. Jennings calls the press the most elaborate and well-constructed example in the entire region. It had a brick roof, white mosaic floor, and crushing machinery, and was housed in a building made from the same local ashlar sandstone masonry as the palace and bathhouse. He acknowledges that the site, with its wine press and nude statuary, doesn’t always square with ideas people have about the history of Islam. Instead, scholars have demonstrated that Islam’s ban on alcohol and human imagery only gained traction later and has varied in its stringency by place and time. “It just shows that cultural change doesn’t happen the same moment political change does,” Hawari says. “Wine was part and parcel of Umayyad culture and we even see this reflected in their poetry and songs. People don’t switch their habits overnight.” Hamdan Taha, a former director of the Palestinian Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, concurs, explaining that the wine press, along with the art from the site, is further evidence of how the Umayyads, even while introducing a new religion into the region, still clung to existing cultural practices. “The material at Khirbet al-Mafjar shows that the Umayyads didn’t see any contradiction between their art and their religion,” Taha says, “and understood how they could coexist.”

Davis and his team began their excavation work at the Hill of Ward in 2014, supported by the Meath County Council, the Irish Office of Public Works, and the Royal Irish Academy. They nearly immediately unearthed evidence of large-scale burning activity—but Davis cautions against connecting the find to Samhain celebrations without further scrutiny.

Davis and his team began their excavation work at the Hill of Ward in 2014, supported by the Meath County Council, the Irish Office of Public Works, and the Royal Irish Academy. They nearly immediately unearthed evidence of large-scale burning activity—but Davis cautions against connecting the find to Samhain celebrations without further scrutiny. Davis and his team suspect that other people may have been buried at the site, and that it might in fact once have been the location of a passage tomb, or a narrow gallery with one or more burial chambers around it. The Boyne Valley has more than 40 such tombs and the Hill of Ward is within sight of several of them, each of which would have required knowledge of architecture, engineering, and even astronomy. All of the passage tombs were built in the Neolithic (4000–2500 B.C.) and represent early examples of ceremonial burials. The earliest phases of the Hill of Ward site date to the later Bronze Age, but Neolithic finds there, including two stone axes, two small pieces of pottery, and a javelin head, suggest that deeper, stony layers could contain an even older phase of use. “It is easy to imagine that an early passage tomb is indeed here,” says Davis, “and that the location continued to be a focus for ceremonies after the tomb was either abandoned or collapsed, or was simply incorporated into a later phase.”

Davis and his team suspect that other people may have been buried at the site, and that it might in fact once have been the location of a passage tomb, or a narrow gallery with one or more burial chambers around it. The Boyne Valley has more than 40 such tombs and the Hill of Ward is within sight of several of them, each of which would have required knowledge of architecture, engineering, and even astronomy. All of the passage tombs were built in the Neolithic (4000–2500 B.C.) and represent early examples of ceremonial burials. The earliest phases of the Hill of Ward site date to the later Bronze Age, but Neolithic finds there, including two stone axes, two small pieces of pottery, and a javelin head, suggest that deeper, stony layers could contain an even older phase of use. “It is easy to imagine that an early passage tomb is indeed here,” says Davis, “and that the location continued to be a focus for ceremonies after the tomb was either abandoned or collapsed, or was simply incorporated into a later phase.”