Letter from Philadelphia

Empire of Glass

By MARGARET SHAKESPEARE

Monday, February 13, 2017

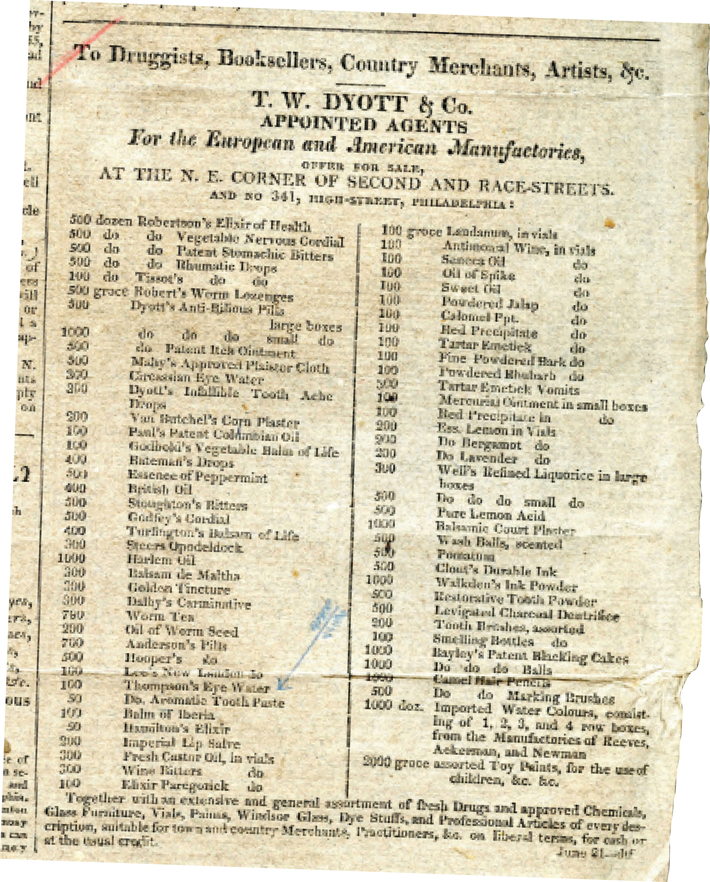

Thomas W. Dyott arrived in Philadelphia from England some time around 1803 with little besides a formula for bootblack and a few shillings in his pocket—and ambitious dreams in his head. He probably lacked the credentials for it, but that didn’t stop him from setting up shop as an apothecary—the nineteenth-century equivalent of a pharmacist—at the corner of Race and Second Streets, referring to himself as “Dr. Dyott,” and assuming all the airs that went with the honorific. “He was into hyperbole for sure,” says Ingrid Wuebber, a historian with the Cultural Resources Department of the engineering firm AECOM. “And he had to have been well-spoken because people believed him and sought his advice.” It wasn’t long before Dyott put his stamp on both the pharmaceutical trade and Philadelphia history. Though he is less well remembered today, he stands alongside William Penn, Benjamin Franklin, Betsy Ross, Rocky Balboa, and the 2008 Phillies—the real, apocryphal, fictitious, and heroic characters of the city’s history.

From his shop, Dyott formulated and produced a range of patent medicines, and eventually set up a distribution network across the United States. Wherever his pharmaceuticals were sold, he advertised. “He was an early ad man,” says Wuebber, who has studied what few records there are of Dyott’s life and found newspaper ads for a variety of his products. “He was an innovator and he saw [business] in an integrated way. His distribution and networking played out beyond pharmaceuticals.” Indeed, Dyott soon added glass manufacturing to his portfolio, which eliminated the need to purchase medicine bottles. Beginning around the turn of the nineteenth century, the area of present-day Kensington-Fishtown, today one of Philadelphia’s hippest neighborhoods, became a center for the glass industry. It was there that Dyott established an empire of glass, which he called Dyottville.

From his shop, Dyott formulated and produced a range of patent medicines, and eventually set up a distribution network across the United States. Wherever his pharmaceuticals were sold, he advertised. “He was an early ad man,” says Wuebber, who has studied what few records there are of Dyott’s life and found newspaper ads for a variety of his products. “He was an innovator and he saw [business] in an integrated way. His distribution and networking played out beyond pharmaceuticals.” Indeed, Dyott soon added glass manufacturing to his portfolio, which eliminated the need to purchase medicine bottles. Beginning around the turn of the nineteenth century, the area of present-day Kensington-Fishtown, today one of Philadelphia’s hippest neighborhoods, became a center for the glass industry. It was there that Dyott established an empire of glass, which he called Dyottville.

For about a decade, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) has been engaged in a massive redevelopment of I-95 along the Delaware River in Philadelphia, including a three-mile stretch directly north of Center City through the neighborhoods of Kensington-Fishtown, Port Richmond, and Northern Liberties. The project came with a multiyear cultural resource effort, led by PennDOT project manager Elaine Elbich and archaeologist Catherine Spohn, along with AECOM archaeologists George Cress and Douglas Mooney. “Digging I-95,” the umbrella name adopted for the excavations, findings, pop-up exhibitions, website, and more, has yielded around a million artifacts that span nearly 6,000 years of human activity, from prehistory through the Industrial Revolution to World War I. In particular, the excavations have uncovered rich nineteenth-century deposits, with an especially massive quantity of early American glass from the Dyottville Glass Works and neighborhoods nearby where many glass factory workers lived.

“The focus on Philly has always been on downtown, but what we’ve found [in these neighborhoods] are extraordinary histories,” says Mooney, who has worked on downtown digs such as the President’s House in Independence National Historical Park. “This area is better preserved, even though there has been more than 300 years of development.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

The First American Revolution

Kings of Cooperation

The Road Almost Taken

Letter from Philadelphia

From the Trenches

Digging up Digital Music

Off the Grid

Revisiting Montezuma Castle

Secret Spaces

Something New for Sutton Hoo

A Surprise City in Thessaly

Zinc Zone

Behind the Curtain

Royal Gams

A Mix of Faiths

Neolithic FaceTime

Bathing, Ancient Roman Style

The Church that Transformed Norway

Siberian William Tell

A Traditional Neanderthal Home

Artifact

Self-expression in the Bronze Age

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Not many specifics of Dyott’s life are known, but experts on the Digging I-95 project have sought out archives and other records to learn more. Research is ongoing, and new information about Dyott and the community he established continues to emerge. In 1830, Dyott set up his newly arrived brother Michael as superintendent of the glassworks, and the “doctor” turned his attention to a grander scheme. He had acquired or leased around 350 acres to make his entire operation self-sufficient agriculturally, domestically—and morally. He began to expand the Dyottville community, with a strong emphasis on creating a proper moral environment for his workers, in particular the factory’s young apprentices. The complex eventually included a 300-acre farm and some 50 buildings, among them a chapel, an infirmary, homes for married employees (often entire families worked in the business), and dormitories for single men and women. Field workers, butchers, bakers, cooks, carpenters, blacksmiths, laundresses, and teachers were all on the payroll. “He encouraged workers to take up a hobby, music, or sports,” says Mooney. Those who signed a contract to live in Dyottville agreed to certain rules, including regular attendance at Methodist services. “And no cussing, no drinking,” Mooney adds. The regulations were spelled out in a 39-page pamphlet published in 1833, “An Exposition of the System of Moral and Mental Labor, Established at the Glass Factory of Dyottville.”

Not many specifics of Dyott’s life are known, but experts on the Digging I-95 project have sought out archives and other records to learn more. Research is ongoing, and new information about Dyott and the community he established continues to emerge. In 1830, Dyott set up his newly arrived brother Michael as superintendent of the glassworks, and the “doctor” turned his attention to a grander scheme. He had acquired or leased around 350 acres to make his entire operation self-sufficient agriculturally, domestically—and morally. He began to expand the Dyottville community, with a strong emphasis on creating a proper moral environment for his workers, in particular the factory’s young apprentices. The complex eventually included a 300-acre farm and some 50 buildings, among them a chapel, an infirmary, homes for married employees (often entire families worked in the business), and dormitories for single men and women. Field workers, butchers, bakers, cooks, carpenters, blacksmiths, laundresses, and teachers were all on the payroll. “He encouraged workers to take up a hobby, music, or sports,” says Mooney. Those who signed a contract to live in Dyottville agreed to certain rules, including regular attendance at Methodist services. “And no cussing, no drinking,” Mooney adds. The regulations were spelled out in a 39-page pamphlet published in 1833, “An Exposition of the System of Moral and Mental Labor, Established at the Glass Factory of Dyottville.”