Features

After the Battle

By DANIEL WEISS

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

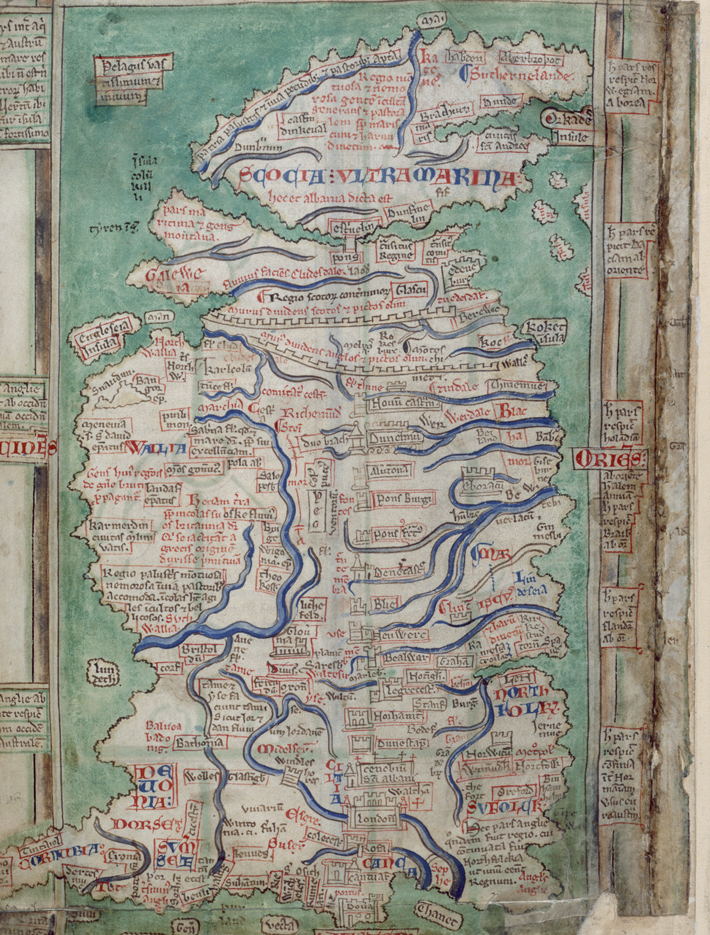

On September 3, 1650, between Doon Hill and the London Road in Dunbar, Scotland, the English Parliamentary army led by Oliver Cromwell battled the Scottish Covenanting army. By this time, the series of conflicts known as the English Civil Wars had raged, off and on, for eight years. At the outset, Cromwell and the Scots had been on the same side, opposed to the royalists who backed King Charles I. The king had been beheaded the previous year, and now the Scots were supporting the royal claim of his son, Charles II.

The Scots are thought to have had as much as a two-to-one advantage in men, and held a superior position on the hill. However, many of the Scots were novices who had been recruited over the summer to replace more experienced soldiers purged from the army for their dissenting political views. When the Scots set out to attack at first light, Cromwell’s forces pounced and made quick work of them. The Battle of Dunbar was over in an hour, with the Scots suffering the overwhelming majority of casualties.

“I imagine it was quite chaotic. Cromwell’s men were trained professionals, and the Scots weren’t in good condition when they went into that battle,” says Chris Gerrard, an archaeologist at the University of Durham. “They had been at war for many years, and the clans were tired of giving up their best to the army. It was just men against boys.”

In the aftermath, several thousand sick and wounded Scottish soldiers were allowed to go home, but some 4,000 others deemed a potential threat were taken prisoner and marched south into England toward Durham, 100 or so miles away. These captives, many still teenagers and away from home for the first time in their lives, were in for a series of horrific travails. Already malnourished, they would suffer extreme privation and languish in unsanitary confines. Those who survived would be dispersed throughout the British Isles and as far afield as North America, where some would go on to lead improbably prosperous lives, with countless descendants living in the United States today. Although generally aware of their Scottish ancestry, many of these descendants knew little of what their seventeenth-century forebears had gone through—until an archaeological excavation produced new evidence of the harrowing events of more than 350 years ago.

As they made their way south toward Durham, the Scottish prisoners were in the charge of Sir Arthur Hesilrige, Cromwell’s governor at Newcastle. He explained what became of them in a letter to the English Council of State for Irish and Scottish Affairs dated October 31, 1650. The captives hadn’t been given a morsel to eat, and 30 miles into the march a number collapsed, claiming they could not go on. Parliamentary troops shot several dozen protesters, and the rest, resigned, continued on their way. Penned into a walled garden for the night farther along, the famished captives dug up raw cabbages and wolfed them down, muddy roots and all, so that they “poysoned their Bodies,” Hesilrige wrote. Based on his account, it seems that around one in four of the captives died on the march to Durham from starvation, exhaustion, execution, or an intestinal condition that he termed “the Flux.”

There is evidence that the Scots thought men would fight in a more “kingly” fashion if they were hungry, Gerrard says, so they probably hadn’t eaten much even before the battle. “They then were marching for six or seven days, and that is quite a time to go without food if you are walking a hundred miles.”

The Blackener’s Cave

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, May 09, 2017

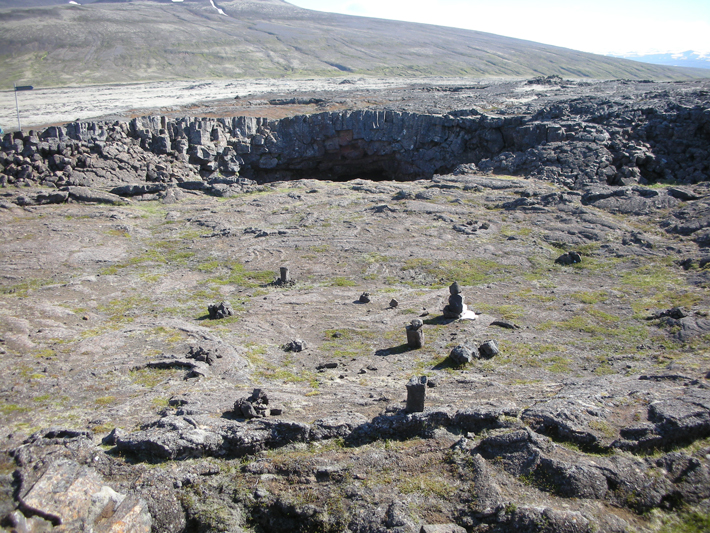

The Hallmundarhraun lava field—basalt dark, with great swells and a froth of white moss—looks like a stormy sea whipped into a frenzy and frozen in place. It begins under the Langjökull glacier in mountains to the east and winds some 30 miles to Hraunfoss—literally, “Lava Falls”—where a crystalline river of meltwater pours directly from its wide, stony face. It’s very Icelandic: fire and ice, water and stone. When the lava flowed at the end of the ninth century, shortly after the Vikings arrived on the island, it was probably the first volcanic activity of its kind that northern Europeans had ever witnessed. Those early residents of western Iceland may have heard eruptions, seen a fiery glow on the horizon, and tracked its spread across the landscape, a spread that ultimately consumed around 90 square miles.

Hallmundarhraun, just a few hours’ drive from Reykjavík, is riven with lava tubes which form when fresh molten rock flows through an existing field of cooled lava. Over time, the ceilings of some of these tunnels partially collapse to form caves. There are some 500 across Iceland, and around 200 hold evidence of human occupation. One of these caves is Surtshellir, part of a lava tube complex that is Iceland’s longest, at more than two miles. It is named for Surtr, the elemental fire giant of Norse mythology, the “scorcher” or “blackener,” ruler of Muspelheim, who will kill all gods and life at the end of time. Inside is one of the more enigmatic archaeological sites on the island.

Until one is almost directly on top of Surtshellir’s entrance, an amphitheater-shaped depression, the arrested turbulence and uniform darkness of Hallmundarhraun conceals it. But the cave is no minor feature. It is giant-scaled, a leviathan’s burrow up to 40 feet in diameter, littered with massive, angular blocks of basalt calved from the ceiling. Around 100 yards into the cave, that ceiling opens to the sky, the result of a collapse centuries ago. Just before reaching this skylight, one encounters, partially buried under boulders from the ceiling, a titanic man-made wall, 15 feet tall and spanning the cave, made up of blocks, each weighing up to four tons. Just past the skylight, two small galleries branch off, one to the left and one to the right. These side caves, Vígishellir (“Fortress Cave”) on the left and Beinahellir (“Bones Cave”) on the right, are the remnants of an older, smaller lava tube bisected by Surtshellir. After one scrambles up a rockfall into Vígishellir, the darkness descends like a shroud. Light is swallowed and incidental sound amplified. Breath hangs in the still, cold, humid air.

A few yards into Vígishellir is a second man-made structure: an anomalous arrangement of stones, piled a few feet high to form an oval enclosure, 22 by 11 feet. Archaeologists believe it could be the oldest standing Viking structure in the world. Next to it is a pile of animal bones, methodically hacked into tiny pieces. Archaeological sites generally have telltale patterns that show scientists how they were used: domestic activity, craft production, ritual. Surtshellir eludes such clarities. The things it contains—and, more importantly, doesn’t contain—fit some patterns and resist others, and show just how difficult it can be to divine behavior, intent, and even emotion from bits of stone and bone.

The Wall at the End of the Empire

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, April 10, 2017

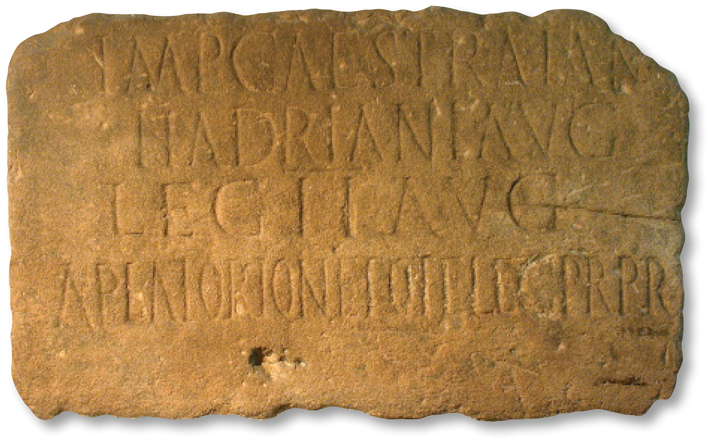

When the emperor Hadrian visited the province of Britannia in A.D. 122, he was in full command of the entire Roman Empire, which stretched some 2,500 miles east from northern Great Britain to modern-day Iraq, and 1,500 miles south to the Sahara Desert. He had become emperor five years earlier, after a controversial postmortem adoption by his predecessor and guardian Trajan, and he ruled until his death in 138, at the age of 62, likely of a heart attack. In just over 20 years, he became, according to an anonymous ancient source, the “most versatile” of the Roman emperors. He was a battle-tested solider who fought with Trajan in Dacia, a skilled politician who masterminded the consolidation of the empire’s territory, a faithful patron and lover of the arts, and a tireless traveler who visited nearly half the empire during his reign.

Hadrian is perhaps best known, however, as one of Rome’s most prodigious builders. In this he followed in the emperor Augustus’ footsteps as a ruler who grasped architecture’s inherent ability to express ideology and power. For most of Hadrian’s reign, the empire was at relative peace—the Pax Romana, or “Roman Peace,” was at its height. Thus he didn’t achieve the notable military victories of some of his predecessors. Instead, he turned to art and architecture as a way of legitimizing his rule, demonstrating Roman dominion, solidifying his legacy, and leaving his enduring stamp on the landscape of the empire.

In Rome itself, the emperor sponsored numerous building projects, both to enrich the lives of its citizens and tie himself to the city’s past. At the site of the Pantheon, the spectacular domed temple in the heart of Rome that Hadrian is credited with completing, he linked his own rule to one of Rome’s most revered men, the first-century B.C. consul Marcus Agrippa—a great builder in his own right. Hadrian chose to retain the facade of Agrippa’s much earlier temple on the front of the Pantheon, while at the same time providing a new venue for the worship of all the gods. Hadrian also designed what is thought to have been the largest temple in ancient Rome, an enormous edifice honoring the goddess Venus Felix, a “bringer of good fortune,” and Roma Aeterna, or “Eternal Rome,” a double dedication whose symbolism, like the immense temple itself, was impossible to miss. Outside Rome, Hadrian displayed his personal love of all things Greek, and he combined it with the clear message that Rome was now in charge. In Athens, for example, he restored the Greek Olympieion, or Temple of Olympian Zeus, and erected a new gold-and-ivory statue to the god, but also placed four statues of himself in front of the main shrine and a large Roman-style arch at the entrance to the temenos, or sanctuary.

In the provinces, as in Rome, architecture served symbolic as well as utilitarian purposes. Hadrian sponsored the renovation of ancient cities such as Smyrna, now Izmir in modern Turkey, founded entirely new ones such as Antinoopolis in Egypt, and commissioned the construction of public architecture—theaters, temples, arches, municipal buildings, and countless statues and inscriptions—everywhere he went. These sites often exhibit a mix of local and imported styles and tastes, and brought what Duke University historian Mary Boatwright calls a “‘Roman’ visual vocabulary” to much of the empire, uniting the vast territory in a way that proclamations and policy often could not. But there was one place where the emperor thought something entirely different was required.

In the provinces, as in Rome, architecture served symbolic as well as utilitarian purposes. Hadrian sponsored the renovation of ancient cities such as Smyrna, now Izmir in modern Turkey, founded entirely new ones such as Antinoopolis in Egypt, and commissioned the construction of public architecture—theaters, temples, arches, municipal buildings, and countless statues and inscriptions—everywhere he went. These sites often exhibit a mix of local and imported styles and tastes, and brought what Duke University historian Mary Boatwright calls a “‘Roman’ visual vocabulary” to much of the empire, uniting the vast territory in a way that proclamations and policy often could not. But there was one place where the emperor thought something entirely different was required.

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

The Wall at the End of the Empire

The Blackener’s Cave

After the Battle

Letter from Greenland

From the Trenches

Scroll Search

Off the Grid

A Cornucopia of Condiments

Bronze Age Bling

Squeezing History from a Turnip

Aurignacian School of Art

Common Ground

Standing Still in Beringia?

The Vikings’ Wide Reach

Close Quarters

The Third Reich’s Arctic Outpost

The Buddha of the Lake

World Roundup

Maya land sharks, exotic libations in Ghana, Viking toy ship, Abu Dhabi’s Neolithic building boom, and the world’s oldest silk

Artifact

How the Maya kings made it rain

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Ultimately, these men were able to obtain their freedom—either by saving up funds equivalent to their sale price or completing a five- to seven-year term of service. Many then settled in southern Maine near the Great Works River sawmill, married, and had children. “They were really on the edge of the frontier,” says Baker. He notes that the area was the target of multiple attacks by Native Americans, in which some of the Scots were taken captive or killed. The McIntire Garrison House, dating to the early eighteenth century and among the oldest private dwellings still standing in Maine today, was built to protect against these raids. “They lived pretty tough lives,” Baker says.

Ultimately, these men were able to obtain their freedom—either by saving up funds equivalent to their sale price or completing a five- to seven-year term of service. Many then settled in southern Maine near the Great Works River sawmill, married, and had children. “They were really on the edge of the frontier,” says Baker. He notes that the area was the target of multiple attacks by Native Americans, in which some of the Scots were taken captive or killed. The McIntire Garrison House, dating to the early eighteenth century and among the oldest private dwellings still standing in Maine today, was built to protect against these raids. “They lived pretty tough lives,” Baker says. In the centuries since the Battle of Dunbar prisoners were held in Durham, human remains were occasionally found near the cathedral, which is still active, and the castle, which now serves as housing for University of Durham students. But they were never analyzed or carefully documented—nor was it clear whether they belonged to some of the 1,600 Scottish soldiers who had died there or to a known burial ground near the cathedral.

In the centuries since the Battle of Dunbar prisoners were held in Durham, human remains were occasionally found near the cathedral, which is still active, and the castle, which now serves as housing for University of Durham students. But they were never analyzed or carefully documented—nor was it clear whether they belonged to some of the 1,600 Scottish soldiers who had died there or to a known burial ground near the cathedral.