Features

Set in Stone

By Eric A. Powell

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Around 8,000 years ago, in the woodlands of what is now the eastern United States, hunter-gatherers began to make stone objects with holes drilled in them that have no parallel in any other prehistoric society. Today, archaeologists call these highly polished and sometimes elaborate objects “bannerstones.” The name was coined by early twentieth-century scholars who thought they must have been mounted on shafts and used as emblems or ceremonial weapons. But just why they were made only during the so-called Archaic period, which ended around 3,000 years ago, has been debated by archaeologists for more than a hundred years.

Some have taken the position that they were not strictly ceremonial and were used as weights that imparted force and accuracy to spear-throwers, or atlatls. They were made from a wide variety of stone materials and in different sizes and shapes, though many take a “butterfly” form, so they may not all have been used for the same purposes. “Archaeologists are mystified by bannerstones,” says University of Florida archaeologist Kenneth Sassaman, who has studied the artifacts in detail. “We can’t know for sure what Archaic people were doing with them.”

The latest scholar attracted to the mystery of bannerstones is Fashion Institute of Technology art historian Anna Blume, who is making an intensive study of these artifacts in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. She has spent countless hours studying the objects. “Bannerstones get noisier and noisier the more time I spend with them,” says Blume. “These extraordinary Native American works from deep time still have a lot to tell us.” Her project is one of several that are providing a new vantage point from which to observe these intriguing objects, which Blume calls “still lifes in stone.”

In the 1930s, University of Kentucky physicist-turned-archaeologist William Webb began excavating graves left by a culture known as the Shell Mound Archaic in Kentucky’s Green River Valley. Helped by a team of Works Progress Administration laborers, Webb unearthed a number of the drilled stones, which were by then already known as bannerstones. Because he found them lying between hooks and handles made of antler, he assumed they had once been connected to a wooden atlatl that had since disintegrated.

Atlatls are essentially throwing sticks with a handle on one end and a hook on the other that can hold a spear. By drawing the spear-thrower back and then hurling it forward, a hunter can use the atlatl as a lever to launch a spear, sending it farther and with more power than if launched only by hand. Webb assumed the bannerstones were meant to somehow increase the efficiency of such spear-throwers. Perhaps inspired by his background in physics, Webb made a long study of atlatl mechanics and determined that bannerstones were used as weights that added velocity and power to the spears hurled from the atlatl. Since Webb published his ideas in 1957, at least two generations of archaeologists have tried to replicate his results. Despite the fact that they are often still referred to as atlatl weights, scholars have largely been unable to show that bannerstones improve atlatl efficiency. “Like a lot of my colleagues, I experimented early on with atlatls and bannerstones,” says Alan Harn, curator emeritus at Dickson Mounds State Park in Illinois. “I must have cast hundreds of spears trying to understand them, but I never got a bannerstone to add thrust and power. They slowed me down.” Eventually, Harn gave up.

Egypt’s Final Redoubt in Canaan

By ROGER ATWOOD

Monday, June 12, 2017

For three centuries, Egyptians ruled the land of Canaan. Armies of chariots and 10,000 foot soldiers under the pharaoh Thutmose III thundered through Gaza and defeated a coalition of Canaanite chiefdoms at Megiddo, in what is now northern Israel, in 1458 B.C. The Egyptians then built fortresses, mansions, and agricultural estates from Gaza to Galilee, taking Canaan’s finest products—copper from Dead Sea mines, cedar from Lebanon, olive oil and wine from the Mediterranean coast, along with untold numbers of slaves and concubines—and sending them overland and across the Mediterranean and Red Seas to Egypt to please its elites.

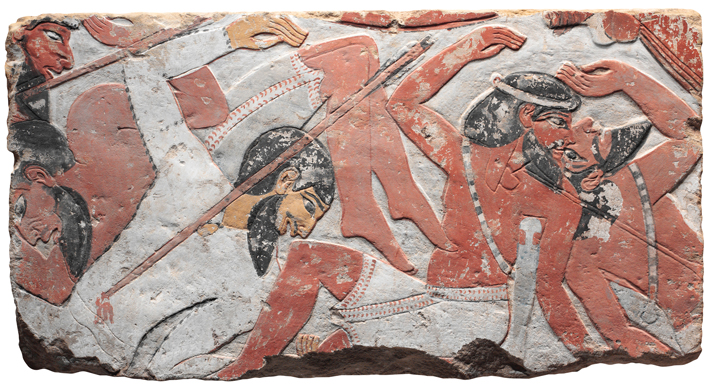

As with many colonial ventures before and since, military conquest led to a new cultural order in the occupied lands. Across Israel, archaeologists have found evidence that Canaanites took to Egyptian customs. They created items worthy of tombs on the Nile, including clay coffins modeled with human faces and burial goods such as faience necklaces and decorated pots. They also adopted Egyptian imagery such as sphinxes and scarabs. For the Egyptians, Canaan was a major trophy. Artists in Egypt carved and painted narratives on the stone walls of temples boasting about vanquished subjects and depicting Canaanite prisoners naked and bound at the wrists.

As with many colonial ventures before and since, military conquest led to a new cultural order in the occupied lands. Across Israel, archaeologists have found evidence that Canaanites took to Egyptian customs. They created items worthy of tombs on the Nile, including clay coffins modeled with human faces and burial goods such as faience necklaces and decorated pots. They also adopted Egyptian imagery such as sphinxes and scarabs. For the Egyptians, Canaan was a major trophy. Artists in Egypt carved and painted narratives on the stone walls of temples boasting about vanquished subjects and depicting Canaanite prisoners naked and bound at the wrists.

Yet Egypt’s presence in Canaan ended sooner than the pharaohs might have expected. With Canaan under assault from seaborne invaders and hit by drought so severe it caused food shortages, Egypt’s colonial rule began to crumble around 1200 B.C., starting in the north and gradually spreading south. Egypt did not fall alone. The eastern Mediterranean’s two other great powers of the day, the Hittites in central Turkey and the Mycenaeans in Greece, saw their capitals sacked and their governments fail. They all toppled in the pan-Mediterranean Late Bronze Age collapse of the twelfth century B.C. Egypt’s 2,000-year-old dynastic system survived, but it lost its trade ties throughout the Mediterranean and its valuable outposts in Canaan.

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Ka-Ching!

Off the Grid

While You Are Waiting

A Dangerous Island

House Rules

Renaissance Melody

Take Me Out to the Ball Game

Tomb Couture

Not So Pearly Whites

Late Paleolithic Masterpieces

Afterlife on the Nile

Knight Watch

The Grand Army Diet

Angry Birds

World Roundup

First World War booze, Russian bear grease, Mediterranean mystery religion, and exploring under Algiers

Artifact

A venerable bead

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

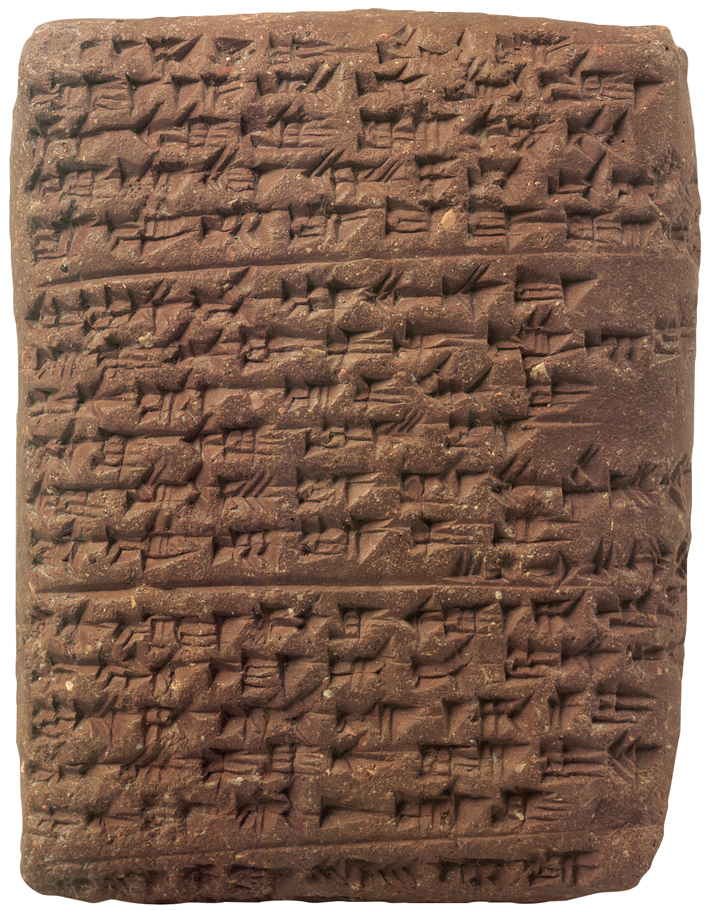

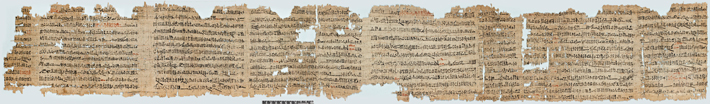

The beginning of Egyptian rule in Canaan, with that smashing victory at Megiddo, is much clearer than its end. Archaeologists digging the remains of Egyptian sites in Israel and combing through ancient texts carved into temple walls and scratched onto clay tablets have never been able to pinpoint exactly when, or even how, Egypt’s occupation of Canaan expired. Did it decline slowly or end suddenly? Was it an orderly withdrawal or a messy rout? Did it fall in the region-wide cataclysm of the Late Bronze Age or were local factors more to blame?

The beginning of Egyptian rule in Canaan, with that smashing victory at Megiddo, is much clearer than its end. Archaeologists digging the remains of Egyptian sites in Israel and combing through ancient texts carved into temple walls and scratched onto clay tablets have never been able to pinpoint exactly when, or even how, Egypt’s occupation of Canaan expired. Did it decline slowly or end suddenly? Was it an orderly withdrawal or a messy rout? Did it fall in the region-wide cataclysm of the Late Bronze Age or were local factors more to blame? Separated by the Sinai, a bleak and sparsely populated land in antiquity as now, Egypt and Canaan were neighbors whose histories of war, trade, and migration intersected and intertwined over millennia. Egypt’s powerful centralized government ruled along the Nile, where pharaohs built the pyramids of Giza and reigned like gods over people who worshipped them. In contrast, Canaan was a land of warring city-states and hill tribes, spread out over what are now Israel, Lebanon, southwestern Syria, and the West Bank. At Canaan’s peak, there were about 20 such city-states in the southern area alone. Their culture was rustic, their power decentralized and weak.

Separated by the Sinai, a bleak and sparsely populated land in antiquity as now, Egypt and Canaan were neighbors whose histories of war, trade, and migration intersected and intertwined over millennia. Egypt’s powerful centralized government ruled along the Nile, where pharaohs built the pyramids of Giza and reigned like gods over people who worshipped them. In contrast, Canaan was a land of warring city-states and hill tribes, spread out over what are now Israel, Lebanon, southwestern Syria, and the West Bank. At Canaan’s peak, there were about 20 such city-states in the southern area alone. Their culture was rustic, their power decentralized and weak. There were other objectives as well. Ruling Canaan allowed Egypt to check the expansion of the Hittite Empire and gave it control over trade routes from central Asia to the Mediterranean. “Egypt’s reason for being in Canaan was, first, strategic,” says archaeologist Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University. “Canaan was important as a bridge to the north and the international routes to ports on the Mediterranean. Egypt could also exploit Canaan’s agricultural output,” he says. “The Egyptians imposed their rule and brought a certain stability while they exploited the land. Look at other empires through history—British, Roman—and you have that same balance of stability with exploitation.” Canaan’s rulers became vassals of the Egyptian state.

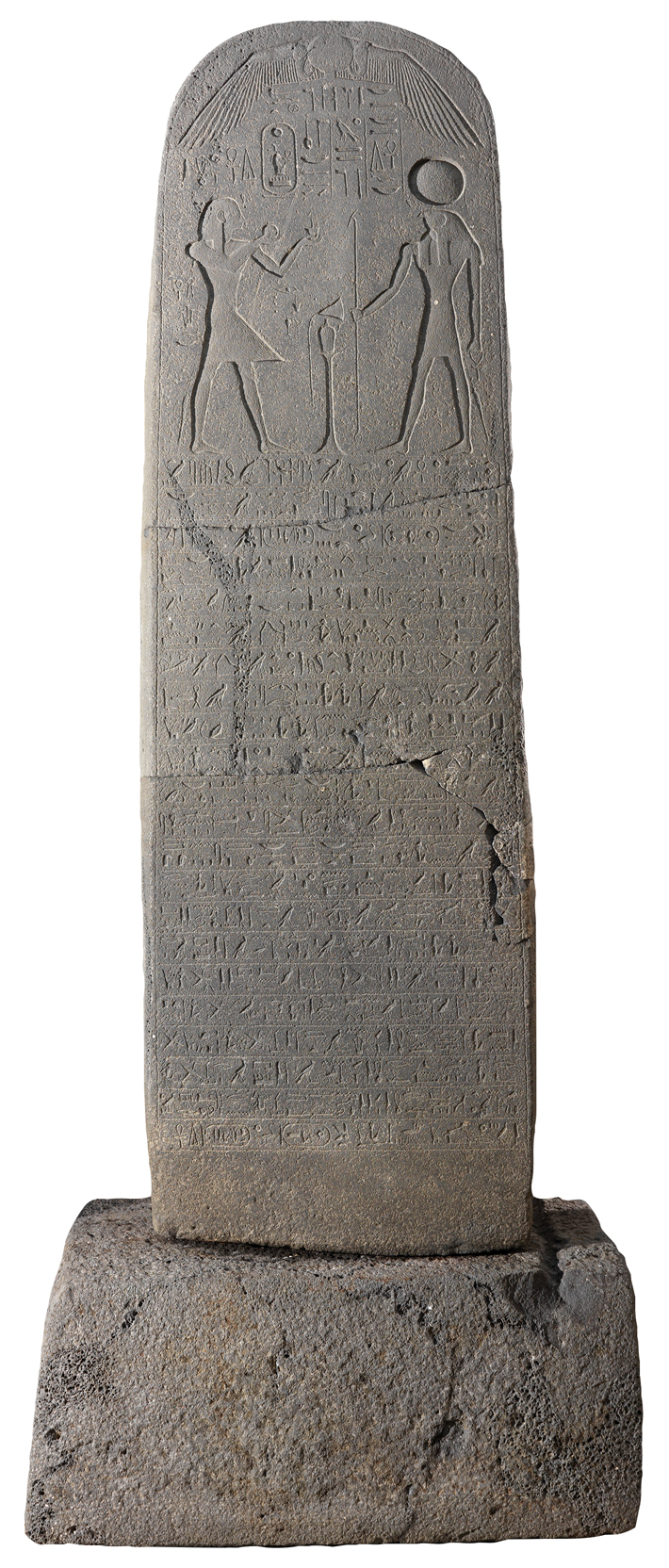

There were other objectives as well. Ruling Canaan allowed Egypt to check the expansion of the Hittite Empire and gave it control over trade routes from central Asia to the Mediterranean. “Egypt’s reason for being in Canaan was, first, strategic,” says archaeologist Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University. “Canaan was important as a bridge to the north and the international routes to ports on the Mediterranean. Egypt could also exploit Canaan’s agricultural output,” he says. “The Egyptians imposed their rule and brought a certain stability while they exploited the land. Look at other empires through history—British, Roman—and you have that same balance of stability with exploitation.” Canaan’s rulers became vassals of the Egyptian state. The Egyptian colonists imported or re-created all the visual propaganda of their power, with objects expressing the permanence of their empire. At the site of Beth Shean, near the Sea of Galilee, a life-size basalt figure of a seated Ramesses III presided over the entrance to one of the main temples. Excavated in the early twentieth century by University of Pennsylvania Museum archaeologists and now in the Israel Museum, the statue was carved from locally quarried stone by imported Egyptian artisans. Beth Shean was occupied mostly by Egyptian soldiers, scribes, and colonial bureaucrats, but, at other sites, ordinary Canaanites would have seen similar political statements. At Hazor, one of ancient Canaan’s largest cities, a team from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem recently found part of a sphinx made of gneiss, a valuable stone used by the Egyptians for statues of gods and rulers. The sphinx bears an inscription to Menkaure (r. 2490–2472 B.C.), a pharaoh who was originally interred in one of Giza’s pyramids. Yet the layer of the excavation in Hazor where the statue was found dates from centuries later in the mid-second millennium B.C. The sphinx had probably been imported from Egypt to lend status to a temple, a relic from the old days meant to lend prestige to Egypt’s new colony.

The Egyptian colonists imported or re-created all the visual propaganda of their power, with objects expressing the permanence of their empire. At the site of Beth Shean, near the Sea of Galilee, a life-size basalt figure of a seated Ramesses III presided over the entrance to one of the main temples. Excavated in the early twentieth century by University of Pennsylvania Museum archaeologists and now in the Israel Museum, the statue was carved from locally quarried stone by imported Egyptian artisans. Beth Shean was occupied mostly by Egyptian soldiers, scribes, and colonial bureaucrats, but, at other sites, ordinary Canaanites would have seen similar political statements. At Hazor, one of ancient Canaan’s largest cities, a team from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem recently found part of a sphinx made of gneiss, a valuable stone used by the Egyptians for statues of gods and rulers. The sphinx bears an inscription to Menkaure (r. 2490–2472 B.C.), a pharaoh who was originally interred in one of Giza’s pyramids. Yet the layer of the excavation in Hazor where the statue was found dates from centuries later in the mid-second millennium B.C. The sphinx had probably been imported from Egypt to lend status to a temple, a relic from the old days meant to lend prestige to Egypt’s new colony.

Along with adopting Egyptian burial practices, or their version of them, the Canaanites also came to worship the Egyptian goddess Hathor. She was associated with love, music, and a kind of feminine grace that Egyptians and Canaanites alike admired, and was the only Egyptian deity absorbed into the Canaanite pantheon. Her distinctive look, with almond-shaped eyes, long curls, and the ears of a cow, appears on objects both plain and fine and in archaeological contexts ranging from houses to palaces.

Along with adopting Egyptian burial practices, or their version of them, the Canaanites also came to worship the Egyptian goddess Hathor. She was associated with love, music, and a kind of feminine grace that Egyptians and Canaanites alike admired, and was the only Egyptian deity absorbed into the Canaanite pantheon. Her distinctive look, with almond-shaped eyes, long curls, and the ears of a cow, appears on objects both plain and fine and in archaeological contexts ranging from houses to palaces.

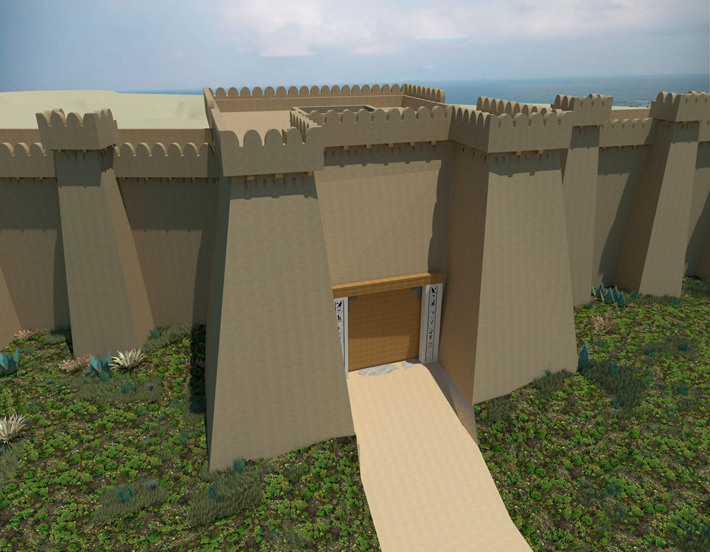

In Egyptian times, anyone entering Jaffa passed under an imposing square gate made of two mudbrick towers joined on top by a wide, two-story wooden bridge that formed a covered passageway. American archaeologist Jacob Kaplan excavated fragments of the gate’s monumental facade around 1960. He found less than half its decorative elements, but enough remained to discern the gate’s carved invocation to Egypt’s—and now Canaan’s—absolute ruler: “Horus-Falcon, Strong Bull, Beloved of Maat, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usermaatre Setepenre, Son of Re, Lord of Crowns, Ramesses.” Burke says, “This gate said to everyone who came, ‘This is Egypt.’”

In Egyptian times, anyone entering Jaffa passed under an imposing square gate made of two mudbrick towers joined on top by a wide, two-story wooden bridge that formed a covered passageway. American archaeologist Jacob Kaplan excavated fragments of the gate’s monumental facade around 1960. He found less than half its decorative elements, but enough remained to discern the gate’s carved invocation to Egypt’s—and now Canaan’s—absolute ruler: “Horus-Falcon, Strong Bull, Beloved of Maat, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usermaatre Setepenre, Son of Re, Lord of Crowns, Ramesses.” Burke says, “This gate said to everyone who came, ‘This is Egypt.’” In the second blaze, mudbricks facing the covered passageway were singed with such heat that they turned a reddish brown, as if fired in a kiln. Ceramics burned to ash. Fragments of antlers belonging to 32 deer that decorated the passageway were partly melted. Passengers aboard ships in the Mediterranean would have seen billows of black smoke as Jaffa’s wood-and-thatch roofs blazed. According to Burke, the circumstantial evidence suggests that Canaanites set the fire themselves. He says, “Could it have been Sea Peoples? Maybe. But the dates we found are 50 years after destructions associated with them.”

In the second blaze, mudbricks facing the covered passageway were singed with such heat that they turned a reddish brown, as if fired in a kiln. Ceramics burned to ash. Fragments of antlers belonging to 32 deer that decorated the passageway were partly melted. Passengers aboard ships in the Mediterranean would have seen billows of black smoke as Jaffa’s wood-and-thatch roofs blazed. According to Burke, the circumstantial evidence suggests that Canaanites set the fire themselves. He says, “Could it have been Sea Peoples? Maybe. But the dates we found are 50 years after destructions associated with them.” Into the beginning of the next century, there would be an Egyptian presence in Beth Shean, says Ben-Tor. “Jaffa wasn’t the last Egyptian center,” she says, “although it fell around the same time as the others.” In any case, nearby Egyptian outposts also experienced fiery ends. Twelve miles inland from Jaffa stood the granary estate of Aphek, where today stand the ruins of a sixteenth-century Ottoman fortress. Excavations in the 1970s by archaeologists from Tel Aviv University found the granary buried under six feet of charred timbers and debris. Aphek’s destruction suggests that the torching of Jaffa was not an isolated attack, but rather a component part of a general insurrection. Burke surmises it probably disrupted Jaffa’s grain supplies, making the Egyptians’ position that much more precarious. In 1125 B.C., the sight, from Jaffa, of smoke rising from Aphek would have made clear that Egypt’s rule in Canaan was over.

Into the beginning of the next century, there would be an Egyptian presence in Beth Shean, says Ben-Tor. “Jaffa wasn’t the last Egyptian center,” she says, “although it fell around the same time as the others.” In any case, nearby Egyptian outposts also experienced fiery ends. Twelve miles inland from Jaffa stood the granary estate of Aphek, where today stand the ruins of a sixteenth-century Ottoman fortress. Excavations in the 1970s by archaeologists from Tel Aviv University found the granary buried under six feet of charred timbers and debris. Aphek’s destruction suggests that the torching of Jaffa was not an isolated attack, but rather a component part of a general insurrection. Burke surmises it probably disrupted Jaffa’s grain supplies, making the Egyptians’ position that much more precarious. In 1125 B.C., the sight, from Jaffa, of smoke rising from Aphek would have made clear that Egypt’s rule in Canaan was over.