From the Trenches

Not So Pearly Whites

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, June 12, 2017

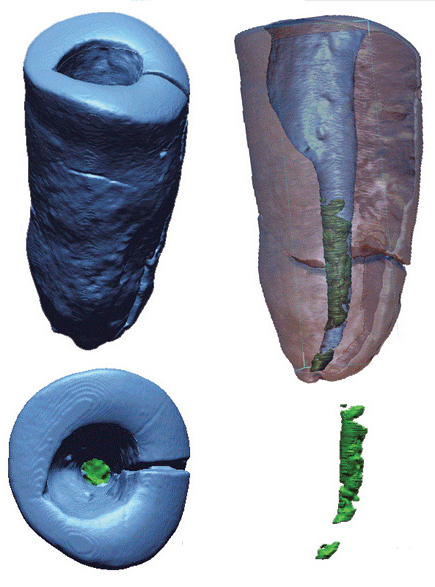

Researchers working near Lucca in northern Italy have found the oldest example of the practice of filling dental cavities, according to Stefano Benazzi of the University of Bologna. Using microscopic techniques, Benazzi and his team determined that two 13,000-year-old front teeth that belonged to a late Pleistocene hunter-gatherer were manipulated with a handheld tool. The Ice Age dentist drilled to remove decaying material within the pulp chambers of the teeth and replaced it with a natural antiseptic paste containing bitumen, vegetal fibers, and hair. This new evidence suggests a more sophisticated technology than previous markings that Benazzi and his colleagues found in teeth from another site in Italy, dated a thousand years earlier. Those teeth are believed to be the first known evidence of human dentistry.

Researchers working near Lucca in northern Italy have found the oldest example of the practice of filling dental cavities, according to Stefano Benazzi of the University of Bologna. Using microscopic techniques, Benazzi and his team determined that two 13,000-year-old front teeth that belonged to a late Pleistocene hunter-gatherer were manipulated with a handheld tool. The Ice Age dentist drilled to remove decaying material within the pulp chambers of the teeth and replaced it with a natural antiseptic paste containing bitumen, vegetal fibers, and hair. This new evidence suggests a more sophisticated technology than previous markings that Benazzi and his colleagues found in teeth from another site in Italy, dated a thousand years earlier. Those teeth are believed to be the first known evidence of human dentistry.

Tomb Couture

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, June 12, 2017

Archaeologists in the northern Chinese city of Datong have completed excavations of a circular tomb dating to the Liao Dynasty (A.D. 907–1125) believed to belong to a husband and wife. An urn with cremated human remains was found in the middle of the tomb. The tomb’s walls feature four vividly colored mural panels that depict cranes, servants, and many articles of dress. The degree of preservation has impressed researchers. In the mural on the west wall, garments colored sky-blue, beige, bluish-gray, yellowish-brown, and pink hang from two clothing stands. One item has a green diamond pattern, with a small red flower that can still be made out at the middle of each diamond.

Renaissance Melody

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, June 12, 2017

Seldom, if ever, do artifacts allow us to experience what people heard in the distant past. But a team excavating at the medieval Convent of the Jacobins in Rennes, France, recently made a discovery that brings to life a short snatch of a song that was last sung by monks in the sixteenth century. Beneath the convent’s refectory, the team found a number of schist plaques inscribed with casual etchings, including caricatures of people, medieval versions of the game of hopscotch, and personal names. Among them was an etching of four lines of diamond shapes that the archaeologists quickly recognized were musical notes representing a short melody of a plainchant, or an unaccompanied sacred song. “It’s very difficult to know just what kind of song the notes record,” says Gaëtan Le Cloirec of the National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research, who led the excavation. “It’s probably a short religious song that was engraved by a Dominican monk as an exercise.” Click below to hear ancient music specialist and soprano Dominique Fontaine sing the melody.

Seldom, if ever, do artifacts allow us to experience what people heard in the distant past. But a team excavating at the medieval Convent of the Jacobins in Rennes, France, recently made a discovery that brings to life a short snatch of a song that was last sung by monks in the sixteenth century. Beneath the convent’s refectory, the team found a number of schist plaques inscribed with casual etchings, including caricatures of people, medieval versions of the game of hopscotch, and personal names. Among them was an etching of four lines of diamond shapes that the archaeologists quickly recognized were musical notes representing a short melody of a plainchant, or an unaccompanied sacred song. “It’s very difficult to know just what kind of song the notes record,” says Gaëtan Le Cloirec of the National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research, who led the excavation. “It’s probably a short religious song that was engraved by a Dominican monk as an exercise.” Click below to hear ancient music specialist and soprano Dominique Fontaine sing the melody.

Take Me Out to the Ball Game

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, June 12, 2017

Today, urban sports arenas are often surrounded by restaurants, bars, and souvenir shops where crowds of people gather before and after an event. New research outside the amphitheater in the Roman city of Carnuntum suggests that the same was true 2,000 years ago. Located east of Vienna, Carnuntum was once one of the largest cities in the Roman Empire, although much of it is unexcavated and hidden from view. Over the past several years, Austrian archaeologists have been using high-resolution magnetometers and ground-penetrating radar to analyze the ancient city’s topography. A recent investigation detected an entire “entertainment district” surrounding Carnuntum’s suburban amphitheater. The scans revealed that the street leading to the amphitheater from the city was lined with an array of inns, shops, bakeries, and Roman “fast food” restaurants (thermopolia) that would have catered to the large crowds attending gladiatorial contests.

House Rules

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, June 12, 2017

The excavations of a royal palace complex within the site of El Palenque in Mexico’s Oaxaca Valley may provide evidence for one of the earliest central governments in the Americas, according to archaeologists Elsa Redmond and Charles Spencer of the American Museum of Natural History. The complex dates to between 300 and 100 B.C. and contains a multiuse building with a sophisticated water management system, a grand private residence, dining facilities, rooms for official functions, and ritual spaces. Radiocarbon samples and ceramics confirm the dating of the palace to a time when states associated with the Zapotec civilization were emerging in the region. To guide the research, the team studied later colonial descriptions of Aztec royal palaces. “We would not expect all the architectural details of a late Postclassic or early colonial period Aztec palace in the basin of Mexico to be the same in prehistoric Zapotec palaces,” Redmond says. “But there are some common aspects of a centralized, hierarchical, and differentiated state administration that might be present in all royal palaces of different time periods.”

The excavations of a royal palace complex within the site of El Palenque in Mexico’s Oaxaca Valley may provide evidence for one of the earliest central governments in the Americas, according to archaeologists Elsa Redmond and Charles Spencer of the American Museum of Natural History. The complex dates to between 300 and 100 B.C. and contains a multiuse building with a sophisticated water management system, a grand private residence, dining facilities, rooms for official functions, and ritual spaces. Radiocarbon samples and ceramics confirm the dating of the palace to a time when states associated with the Zapotec civilization were emerging in the region. To guide the research, the team studied later colonial descriptions of Aztec royal palaces. “We would not expect all the architectural details of a late Postclassic or early colonial period Aztec palace in the basin of Mexico to be the same in prehistoric Zapotec palaces,” Redmond says. “But there are some common aspects of a centralized, hierarchical, and differentiated state administration that might be present in all royal palaces of different time periods.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Ka-Ching!

Off the Grid

While You Are Waiting

A Dangerous Island

House Rules

Renaissance Melody

Take Me Out to the Ball Game

Tomb Couture

Not So Pearly Whites

Late Paleolithic Masterpieces

Afterlife on the Nile

Knight Watch

The Grand Army Diet

Angry Birds

World Roundup

First World War booze, Russian bear grease, Mediterranean mystery religion, and exploring under Algiers

Artifact

A venerable bead

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement