From the Trenches

By the Light of the Moon

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, October 16, 2017

A site in Cornwall known as Hendraburnick Quoit appears to have been host to nighttime rituals starting around 2500 B.C. and continuing for several hundred years. In a recent excavation, researchers led by Andy Jones of the Cornwall Archaeological Unit discovered that a stone at the site contained dozens of circular carvings called cup marks, along with an extensive network of radial lines, all so faint that they are only visible in moonlight or low sunlight, “when the sun casts shadows across the surface of the stone,” says Jones. Previously, just 17 cup marks had been observed on the stone. “We already knew about the most deeply carved cup marks,” he says, “but we only started to be able to see other elements during the excavations later in the day.” Further evidence of activity after dark was provided by the discovery of nearly 2,000 pieces of fragmented quartz, apparently smashed at the site, which would have produced luminescent effects.

A site in Cornwall known as Hendraburnick Quoit appears to have been host to nighttime rituals starting around 2500 B.C. and continuing for several hundred years. In a recent excavation, researchers led by Andy Jones of the Cornwall Archaeological Unit discovered that a stone at the site contained dozens of circular carvings called cup marks, along with an extensive network of radial lines, all so faint that they are only visible in moonlight or low sunlight, “when the sun casts shadows across the surface of the stone,” says Jones. Previously, just 17 cup marks had been observed on the stone. “We already knew about the most deeply carved cup marks,” he says, “but we only started to be able to see other elements during the excavations later in the day.” Further evidence of activity after dark was provided by the discovery of nearly 2,000 pieces of fragmented quartz, apparently smashed at the site, which would have produced luminescent effects.

Tablet Time

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, October 16, 2017

To discover an artifact with writing on it is unusual—but retrieving more than two dozen in one day is exceptional. “When we found the first tablet, we were very excited,” says Andrew Birley, excavation director at the Roman fort of Vindolanda in northern England. “After the second and third one, we suspected we were in for a very special day.” While digging a cobbled surface outside Vindolanda’s first fort (of a total of nine), Birley uncovered 25 wooden tablets inscribed in ink dating to the end of the first century A.D. “Based on the scatter pattern, we’re dealing with someone walking in a line and the tablets dropping, possibly being blown away from the person holding them,” says Birley. “Perhaps they were being carried to be dumped. Or not—there’s no way to tell.”

To discover an artifact with writing on it is unusual—but retrieving more than two dozen in one day is exceptional. “When we found the first tablet, we were very excited,” says Andrew Birley, excavation director at the Roman fort of Vindolanda in northern England. “After the second and third one, we suspected we were in for a very special day.” While digging a cobbled surface outside Vindolanda’s first fort (of a total of nine), Birley uncovered 25 wooden tablets inscribed in ink dating to the end of the first century A.D. “Based on the scatter pattern, we’re dealing with someone walking in a line and the tablets dropping, possibly being blown away from the person holding them,” says Birley. “Perhaps they were being carried to be dumped. Or not—there’s no way to tell.”

More than 2,000 tablets have thus far been unearthed at Vindolanda (“The Wall at the End of the Empire,” May/June 2017). These most recent examples are now undergoing conservation, but one tablet has already started to reveal its secrets. “It’s a request for a leave or holiday by a man called Masclus,” says Birley. “The writing is beautifully clear and in a stunning script. If only I could write like that.”

Spain’s Silver Boom

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, October 16, 2017

After defeating Hannibal and Carthage in the Second Punic War (218–201 B.C.), Rome found itself the dominant power in the western Mediterranean. While it may seem obvious that Rome’s prospects would rise, having vanquished its chief military, economic, and political rival, a new study led by Katrin Westner of Goethe University suggests that it was the massive influx of Iberian-mined silver into the Roman economy that fueled its unprecedented expansion. Researchers analyzed the elemental composition and lead isotope signature of 70 Roman coins issued between 310 and 101 B.C. in order to determine the source of the silver ore. The results show that in the decades before the Second Punic War, Roman silver originated mostly from Aegean sources and Greek colonies in Magna Graecia. However, coins issued after the war had a different isotope signature, one that closely matched known metal sources from the Iberian Peninsula.

After defeating Hannibal and Carthage in the Second Punic War (218–201 B.C.), Rome found itself the dominant power in the western Mediterranean. While it may seem obvious that Rome’s prospects would rise, having vanquished its chief military, economic, and political rival, a new study led by Katrin Westner of Goethe University suggests that it was the massive influx of Iberian-mined silver into the Roman economy that fueled its unprecedented expansion. Researchers analyzed the elemental composition and lead isotope signature of 70 Roman coins issued between 310 and 101 B.C. in order to determine the source of the silver ore. The results show that in the decades before the Second Punic War, Roman silver originated mostly from Aegean sources and Greek colonies in Magna Graecia. However, coins issued after the war had a different isotope signature, one that closely matched known metal sources from the Iberian Peninsula.

The silver mines of southern Spain were an enormous economic resource once exclusively controlled by Carthage, but which Rome appropriated following its victory. This newly acquired reserve, combined with Carthaginian silver acquired as war booty and indemnities paid by Carthage, brought an extraordinary amount of capital into Rome’s coffers.

Conspicuous Consumption

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, October 16, 2017

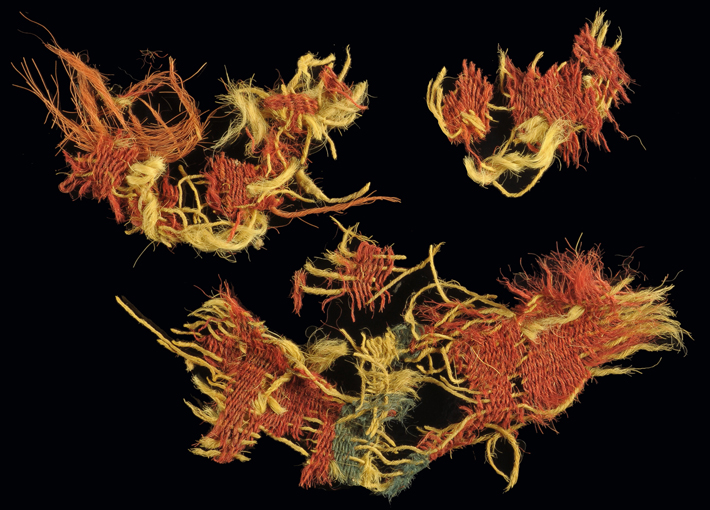

Vividly colored red and blue fragments of wool discovered at a copper mining site in southern Israel’s Timna Valley are offering new insights into the social standing of metalworkers who lived in the remote area. The fragments, which have been radiocarbon dated to 3,000 years ago, are the earliest known examples of textiles treated with plant-based dyes in the Levant. But the plants used to make the dyes—the madder plant for red and most likely the woad plant for blue—could not have been grown in the arid Timna Valley. Nor was there enough water available locally to raise the livestock necessary to provide wool or to dye the fabric. The textiles must, therefore, have been produced elsewhere. According to Naama Sukinek of the Israel Antiquities Authority, the discovery suggests that at least some of the metalworkers at Timna had the resources to purchase this imported cloth. Says Sukinek, “Our finding indicates that the society in Timna included an upper class that had access to expensive and prestigious textiles.”

Itinerant Etruscan Beekeepers

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, October 16, 2017

In northern Italy 2,500 years ago, Etruscans developed a unique system of beekeeping to manufacture honey, beeswax, and other products. Archaeologists working at the site of Forcello recently gained rare insight into ancient beekeeping when they uncovered the charred and melted remains of honey, honeycombs, and honeybees in a workshop that had burned down between 510 and 495 B.C. Researchers conducted chemical and palynological (pollen) analyses of the material to determine not only the composition of Etruscan honey, but also what types of plants bees were collecting pollen from two and half millennia ago. While bees in northern Italy today feed abundantly on nonnative plants that have been introduced to the region, during the Etruscan period, bees were foraging from aquatic sources such as water lilies and the flowers of wild grapevines found along shorelines. This produced a kind of grapevine honey that is completely unknown today. Since these plants were not particularly abundant around Forcello, experts believe that Etruscan beekeepers maintained beehives on boats that moved along river courses and took the harvested honeycombs back to their workshops to extract the honey. “We have tried to study the finds and their context from all possible angles and, surprisingly, we ended up having very strong indications of a nomadic form of beekeeping,” says New York University researcher Lorenzo Castellano. In fact, a passage from the first-century A.D. writer Pliny the Elder’s Natural History mentions a town only about 12 miles from Forcello, and the historian discusses the movements of the beehives by boats. Says Castellano, “Our finds, which are more than five centuries older, appear to confirm Pliny’s narrative.”

In northern Italy 2,500 years ago, Etruscans developed a unique system of beekeeping to manufacture honey, beeswax, and other products. Archaeologists working at the site of Forcello recently gained rare insight into ancient beekeeping when they uncovered the charred and melted remains of honey, honeycombs, and honeybees in a workshop that had burned down between 510 and 495 B.C. Researchers conducted chemical and palynological (pollen) analyses of the material to determine not only the composition of Etruscan honey, but also what types of plants bees were collecting pollen from two and half millennia ago. While bees in northern Italy today feed abundantly on nonnative plants that have been introduced to the region, during the Etruscan period, bees were foraging from aquatic sources such as water lilies and the flowers of wild grapevines found along shorelines. This produced a kind of grapevine honey that is completely unknown today. Since these plants were not particularly abundant around Forcello, experts believe that Etruscan beekeepers maintained beehives on boats that moved along river courses and took the harvested honeycombs back to their workshops to extract the honey. “We have tried to study the finds and their context from all possible angles and, surprisingly, we ended up having very strong indications of a nomadic form of beekeeping,” says New York University researcher Lorenzo Castellano. In fact, a passage from the first-century A.D. writer Pliny the Elder’s Natural History mentions a town only about 12 miles from Forcello, and the historian discusses the movements of the beehives by boats. Says Castellano, “Our finds, which are more than five centuries older, appear to confirm Pliny’s narrative.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Hidden Stories of the York Gospel

Off the Grid

Iconic Discovery

Arctic Ice Maiden

Desert Life

Living Evidence

Putting on a New Face

Fit for a Saint

The Glass Economy

Henry VIII’s Favorite Palace

Itinerant Etruscan Beekeepers

Spain’s Silver Boom

Conspicuous Consumption

Tablet Time

By the Light of the Moon

World Roundup

Viking cod exports, Bronze Age cereal box, Commodore Perry’s Revenge, Easter Island ecology, and Zanzibar’s colonial past

Artifact

A face from the past

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement