The Hidden Stories of the York Gospel

November/December 2017

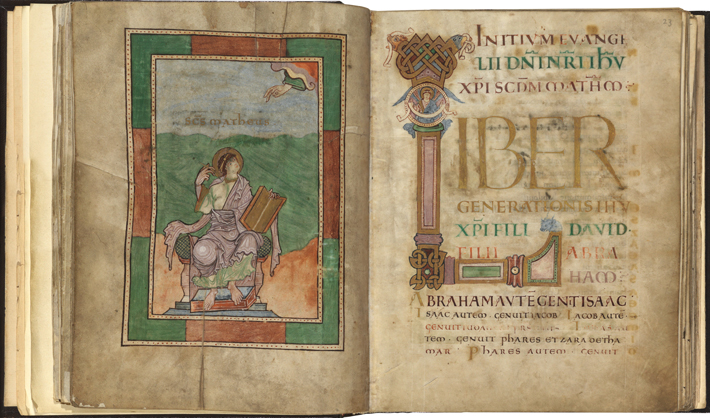

Around A.D. 990, the monks at Saint Augustine’s monastery in Canterbury, England, made an illuminated copy of the four gospels of the New Testament. This parchment manuscript is one of the oldest books in Europe and is still used in ceremonies at the Cathedral and Metropolitan Church of Saint Peter in York, better known as York Minster, where it has been kept since about A.D. 1020. All of that history has left its traces on the book’s pages. Now, researchers have found a way to use erasers to recover DNA from the book’s parchment pages without harming them. DNA sampling typically requires destroying a small piece of whatever is being studied. “There was no way they were going to let us cut the York Gospel,” says Sarah Fiddyment of the University of York, “so being able to do it noninvasively is incredible because we get access to these books that otherwise we’d never get to see.”

The technique that Fiddyment has helped pioneer requires only a white plastic eraser of the kind typically used in drawing classes. She rubs the eraser on the parchment page, creating a triboelectric effect—essentially static electricity—which allows tiny amounts of the parchment and whatever else might be on the page to stick to the bits that come off of the eraser. The eraser waste is then collected and treated with chemicals to recover proteins and DNA. The technique can be used on any protein-based material such as bone or ivory, according to Fiddyment.

The research team’s analysis has been able to show that the book is primarily made of calfskin and that four of the five calves whose gender could be identified were female—not male as might be expected for people who raised cattle for dairying. This finding has led the researchers to speculate that the parchment may have come from cattle that died during an outbreak of a disease called murrain that swept through cattle herds in Great Britain and Ireland during the late 900s.

The research team’s analysis has been able to show that the book is primarily made of calfskin and that four of the five calves whose gender could be identified were female—not male as might be expected for people who raised cattle for dairying. This finding has led the researchers to speculate that the parchment may have come from cattle that died during an outbreak of a disease called murrain that swept through cattle herds in Great Britain and Ireland during the late 900s.

One document that was added to the book in the fourteenth century was made of sheepskin. It records property that was owned by the church in York. In some cases sheepskin was preferred for legal documents because it is not as durable as calfskin. It will come apart if you try to erase what’s written on it, and therefore it is easier to detect whether the writing has been altered.

Human DNA recovered from the book also revealed which pages had been handled most frequently. Aside from a page that had been restored in the mid-twentieth century, which had an anomalously large amount of DNA, those that show the most use were in folio 6, a bundle of calfskin parchment that makes up pages 23–30 in the book. Those pages contain the oaths that the clergy use to swear themselves to the church. “Every canon of York has sworn their oath on this book since the thirteenth century,” says Victoria Harrison, assistant director of collections and learning at York Minster.

The study also revealed a hidden danger to the future preservation of the York Gospel. The DNA of bacteria from the genus Saccharopolyspora, which can cause a measles-like spotting of the pages, was found throughout the book. Conservators will now have a chance to stop the bacteria before it can damage the manuscript.

This work opens up a new area of DNA research—examining parchment documents to study changes in livestock over hundreds of years. “Parchment is this incredible untapped resource,” says Fiddyment. “Basically what you’ve got all over the world is millions of animals that are dated and located.”