Features

The Archaeology of Gardens

Monday, February 12, 2018

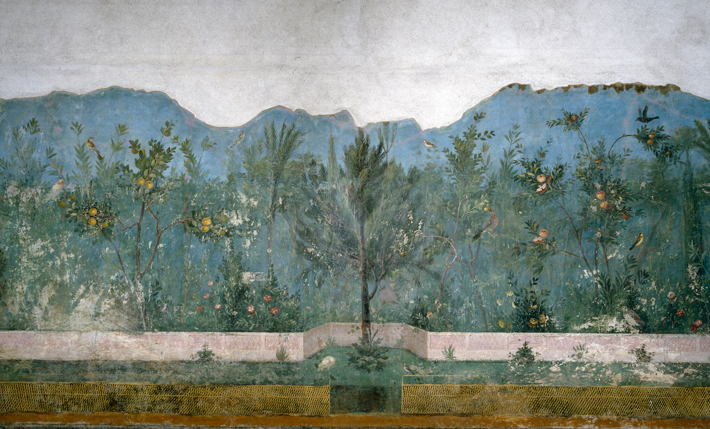

People have created gardens across the world and throughout time, and these spaces have been an essential part of the human experience. Gardens such as Eden, and also Gethsemane, where Jesus prayed and his disciples slept the night before his crucifixion, are, to this day, regarded as sacred. Gardens are also a key element in some of the best-known myths. One of the Labors of Hercules required the hero to steal, from a place on the far edge of the world called the Garden of the Hesperides, the golden apples that the goddess Hera had given to her husband Zeus as a wedding present. The palaces of the ancient Near East are known to have had spectacular gardens, including the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, whose precise location is still unknown.

Beginning in the mid-twentieth century, archaeologists started to apply the full range of methods available to identifying and understanding ancient gardens. As technology has evolved, researchers have not only been able to discover where gardens were located and, generally, what they were used for, but also to determine which individual plants were cultivated and how long they thrived. Along with written sources, this has allowed researchers to see how gardens changed over time and what they can tell us about the people and cultures who nurtured them.

The Viking Great Army

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, February 12, 2018

At first glance, the historic county of Yorkshire in northern England seems as English as can be. It gives its name to Yorkshire pudding, a staple of English cuisine dating back to the eighteenth century. Earlier still, it was home to the royal House of York, whose line included King Richard III. But a closer look reveals a more complicated history. Take Ormesby: Today a suburb of Middlesbrough, its name derives from the Old Norse for “Ormr’s farm.” Or the many streets in the city of York that end in “gate,” from the Old Norse gata, meaning “road” or “way.” Even the city’s name comes from the Old Norse Jorvik.

At first glance, the historic county of Yorkshire in northern England seems as English as can be. It gives its name to Yorkshire pudding, a staple of English cuisine dating back to the eighteenth century. Earlier still, it was home to the royal House of York, whose line included King Richard III. But a closer look reveals a more complicated history. Take Ormesby: Today a suburb of Middlesbrough, its name derives from the Old Norse for “Ormr’s farm.” Or the many streets in the city of York that end in “gate,” from the Old Norse gata, meaning “road” or “way.” Even the city’s name comes from the Old Norse Jorvik.

The source of these Scandinavian-influenced place names and the many more that can be found to this day in northern England dates back more than a thousand years. Starting in the late ninth century, tens of thousands of Vikings arrived in Anglo-Saxon England, first as part of an invading force known as the Viking Great Army, and later as part of a massive wave of settlers. Examining the landscape, history, and archaeology of the region tells us much about what happens when cultures clash but ultimately come to coexist. And it helps explain Anglo-Saxon and Viking interactions.

The Viking Great Army’s arrival in 865 was recounted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: “A great heathen force came into English land, and they took winter-quarters in East Anglia; there they were horsed, and they made peace.” According to the Chronicle, the Vikings spent years campaigning through the territory of the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms—East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, and Wessex. They proved to be masters at keeping the Anglo-Saxons off balance, making peace with a kingdom one year, only to strike a mortal blow the next. By 880, all the kingdoms had fallen to the Vikings except Wessex, with which they made peace. “The Vikings were very quick and they got quite far inland on their boats,” says Jane Kershaw of the University of Oxford. “They had an element of surprise that the Anglo-Saxons weren’t quite able to anticipate and respond to.”

Viking raiders had been targeting wealthy enclaves on England’s coasts with summertime hit-and-run raids since at least 793, when they launched the infamous, terrifying attack on a monastery on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne off the Northumbrian coast of northeast England. Attacks on other monasteries and settlements on England’s east and west coasts followed. Beginning in 850, Viking forces at times spent the winter at coastal sites, allowing them to start their raids earlier in the year. With the arrival of the Viking Great Army, at last, they were able to penetrate deep into England, making their way along rivers and ancient Roman roads, setting up overwintering camps, and wreaking havoc on the Anglo-Saxons. “It seems that the Vikings are after something a little bit different at this stage,” says Kershaw. “They’re still after portable wealth, but they start to have an eye toward acquiring land as well. They start to see England as somewhere they might be able to settle and reestablish themselves as lords with their own families.”

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes the Viking Great Army’s exploits in outsized terms. In a single day’s battle against Wessex, for example, it reports a death toll in the thousands. “The implication is that it’s larger than any previous army seen in England,” says Dawn Hadley of the University of Sheffield. But until recently, there had been little archaeological evidence of its presence. Only one overwintering camp mentioned in the Chronicle had ever been discovered, at Repton, the capital of Mercia, in present-day Derbyshire, where the army spent the winter of 873–874. Excavations conducted there between 1974 and 1993 by Martin Biddle and his late wife, Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle, had revealed a small, heavily defended enclosure covering just an acre or two. Although it was unclear whether the camp extended beyond this fortified area, some experts took these findings to suggest that the Great Army was not actually so great after all, numbering at most in the hundreds—and that the Chronicle’s authors had exaggerated its size to make it appear more fearsome.

Now, however, an archaeological project at another location, Torksey, in Lincolnshire, where the army camped from 872 to 873, has established that it was indeed very large—it was in fact far more than a mere army. According to Hadley, codirector of the Torksey research project along with Julian Richards of the University of York, “We are getting the sense that the force that was at Torksey and that is referred to as an army in the Chronicle actually comprised not just warriors, but people engaged in trade and manufacture, and women and children as well.”

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Mesopotamian Merchant Files

Off the Grid

He’s No Stone Face

Satellites on the Silk Road

Gods of the Galilee

The Venus of Vlakno

Caesar’s English Beachhead

Head in the Sand

Seals of Approval

Early Signs of Empire

Tut’s Mesopotamian Side

Newtonian Whiteboard

Nomadic Chic

Old Woman and the Sea

World Roundup

A rare Neolithic vintage, rock art on the Orinoco, Little Foot the Australopithecus, and medieval bishops’ bachelor pad

Artifact

The early sherd special

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Evidence of the camp at Torksey has been unearthed, for the most part, by avocational metal detectorists. Long active in the United Kingdom, they are strongly encouraged to notify scholars of their finds. When Hadley and Richards learned that a group of detectorists in the Torksey area had discovered ingots, weights, and a concentration of ninth-century coins, including a number of Arabic silver dirhams, all of which appeared to be associated with the Viking Great Army camp, they set out to carefully document the evidence. “We got the detectorists to record their finds more systematically,” says Richards. “We gave them portable global positioning devices to log the coordinates of each discovery so we could plot maps of where everything was coming from.”

Evidence of the camp at Torksey has been unearthed, for the most part, by avocational metal detectorists. Long active in the United Kingdom, they are strongly encouraged to notify scholars of their finds. When Hadley and Richards learned that a group of detectorists in the Torksey area had discovered ingots, weights, and a concentration of ninth-century coins, including a number of Arabic silver dirhams, all of which appeared to be associated with the Viking Great Army camp, they set out to carefully document the evidence. “We got the detectorists to record their finds more systematically,” says Richards. “We gave them portable global positioning devices to log the coordinates of each discovery so we could plot maps of where everything was coming from.”

The camp at Torksey would have been self-sustaining in some respects. “It’s almost like a town on the move,” says Hadley. Life within its confines is becoming clearer for researchers. Members of the army appear to have had leisure time on their hands, as shown by the number of lead gaming pieces that have been found at the site. The presence of metalworkers is indicated by collections of scrap copper and iron, apparently gathered to be melted down. Women seem to have been part of the camp as well, as suggested by the discovery of spindle whorls and other tools used to work textiles. It is unclear, though, whether these were Scandinavian women who had come along with the army as part of families, or captives taken as spoils of war. Added to all this are hints of an aspiring kingdom attempting to establish itself. Three iron plowshares discovered together may have been headed for the scrap heap. But, according to Richards, “The more interesting possibility is that they were already thinking about seizing agricultural estates and acquired the plowshares with that aim in mind.”

The camp at Torksey would have been self-sustaining in some respects. “It’s almost like a town on the move,” says Hadley. Life within its confines is becoming clearer for researchers. Members of the army appear to have had leisure time on their hands, as shown by the number of lead gaming pieces that have been found at the site. The presence of metalworkers is indicated by collections of scrap copper and iron, apparently gathered to be melted down. Women seem to have been part of the camp as well, as suggested by the discovery of spindle whorls and other tools used to work textiles. It is unclear, though, whether these were Scandinavian women who had come along with the army as part of families, or captives taken as spoils of war. Added to all this are hints of an aspiring kingdom attempting to establish itself. Three iron plowshares discovered together may have been headed for the scrap heap. But, according to Richards, “The more interesting possibility is that they were already thinking about seizing agricultural estates and acquired the plowshares with that aim in mind.” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle offers no insights into the nature of the battle for Repton, but evidence shows it was likely a bloody one. Next to a crypt where members of the Mercian royal family were buried, the excavation unearthed a Viking warrior who had suffered grievous injuries and had been laid to rest alongside an iron sword, with a silver Thor’s hammer around his neck. “He died a very violent death indeed,” says Biddle, reflecting back on the discovery. “He looks as though someone stabbed him more or less in the eyes. But the real great wound, which we found immediately upon excavation, was a huge cut into the inner side of his left femur. It could only have been made by someone standing above him, perhaps with a heavy sword or an ax.” A boar’s tusk had been placed between the warrior’s thighs, possibly to replace genitalia damaged or severed in his final battle.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle offers no insights into the nature of the battle for Repton, but evidence shows it was likely a bloody one. Next to a crypt where members of the Mercian royal family were buried, the excavation unearthed a Viking warrior who had suffered grievous injuries and had been laid to rest alongside an iron sword, with a silver Thor’s hammer around his neck. “He died a very violent death indeed,” says Biddle, reflecting back on the discovery. “He looks as though someone stabbed him more or less in the eyes. But the real great wound, which we found immediately upon excavation, was a huge cut into the inner side of his left femur. It could only have been made by someone standing above him, perhaps with a heavy sword or an ax.” A boar’s tusk had been placed between the warrior’s thighs, possibly to replace genitalia damaged or severed in his final battle.

After overwintering at Repton from 873 to 874, the Viking Great Army split in two. One part, under the leadership of Guthrum, headed south and was ultimately defeated in 878 by Wessex and its king, Alfred the Great. To make peace, Guthrum was baptized along with 30 of his warriors, and ended up reigning as an Anglo-Saxon-style king over a swath of territory allocated to him by Alfred. The other part of the army headed north and went on to “share out the land,” as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle puts it, in Northumbria in 876, Mercia in 877, and East Anglia in 880. This seems to suggest that the Vikings took over vast stretches of England, but how did it work exactly? “We don’t really know,” says Kershaw. “The consensus is that they do take over the Anglo-Saxon estates, but I think you probably have Anglo-Saxon communities left in place alongside the new Scandinavian ones.”

After overwintering at Repton from 873 to 874, the Viking Great Army split in two. One part, under the leadership of Guthrum, headed south and was ultimately defeated in 878 by Wessex and its king, Alfred the Great. To make peace, Guthrum was baptized along with 30 of his warriors, and ended up reigning as an Anglo-Saxon-style king over a swath of territory allocated to him by Alfred. The other part of the army headed north and went on to “share out the land,” as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle puts it, in Northumbria in 876, Mercia in 877, and East Anglia in 880. This seems to suggest that the Vikings took over vast stretches of England, but how did it work exactly? “We don’t really know,” says Kershaw. “The consensus is that they do take over the Anglo-Saxon estates, but I think you probably have Anglo-Saxon communities left in place alongside the new Scandinavian ones.”

The area of northern and eastern England inhabited by the Vikings ultimately came to be known as the Danelaw, after the Anglo-Saxons’ belief that most of the invaders had come from Denmark. New evidence suggests that once the army members settled there, large numbers of Viking women came over to join them. Kershaw has analyzed metal-detected finds from rural parts of the Danelaw and identified 125 women’s brooches of types that have turned up nowhere else in England, but have been found in Scandinavia, particularly in Denmark, and date to the Viking Age. “It’s clear that these items are coming in on the clothing of women arriving from southern Scandinavia to settle in rural England,” she says. “So I think there is a second wave of migration following the settlement of the Danelaw that includes women and children.” The discovery of brooches that mix Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian elements indicates that the two communities intermingled to a great degree. “These styles are seen as somehow fashionable by the locals,” says Kershaw. “There is a desire to emulate these styles, which suggests that Scandinavians are either in political control or they’re seen as exotic.”

The area of northern and eastern England inhabited by the Vikings ultimately came to be known as the Danelaw, after the Anglo-Saxons’ belief that most of the invaders had come from Denmark. New evidence suggests that once the army members settled there, large numbers of Viking women came over to join them. Kershaw has analyzed metal-detected finds from rural parts of the Danelaw and identified 125 women’s brooches of types that have turned up nowhere else in England, but have been found in Scandinavia, particularly in Denmark, and date to the Viking Age. “It’s clear that these items are coming in on the clothing of women arriving from southern Scandinavia to settle in rural England,” she says. “So I think there is a second wave of migration following the settlement of the Danelaw that includes women and children.” The discovery of brooches that mix Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian elements indicates that the two communities intermingled to a great degree. “These styles are seen as somehow fashionable by the locals,” says Kershaw. “There is a desire to emulate these styles, which suggests that Scandinavians are either in political control or they’re seen as exotic.”