Gardens

Scientific Gardens

By MARLEY BROWN

Thursday, March 22, 2018

In colonial America, Philadelphia was home base for a community of ardent plant enthusiasts who came together on the banks of the Schuylkill River. There they competed to cultivate exotic specimens, fostering an Enlightenment-era spirit of inquiry that eventually led to the discipline of botany. At the Woodlands, a private estate built between the 1760s and 1780s, wealthy collector William Hamilton amassed what was possibly the largest collection of flora in the country and constructed a state-of-the-art greenhouse known to have been visited by Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton, with the help of his friend and neighbor, seed dealer William Bartram, created a garden dedicated to aesthetics and to building a scientific collection of plants from around the world.

According to archaeologist Sarah Chesney, who identified and excavated the Woodlands’ greenhouse, the structure is an example of Hamilton’s fervor for this project. “You have to be committed to pour resources and time into what was really a non-essential building,” she says. “Its remains are now valuable physical evidence of this remarkable and transient exchange of plants and ideas.” After Hamilton’s death, the estate was eventually sold and the gardens gave way to a public cemetery in the 1840s. “We have a nineteenth-century cemetery superimposed on an eighteenth-century estate,” explains the Woodlands’ executive director Jessica Baumert. “The company used as much of the infrastructure that was already in place as they could to design the cemetery, and that will provide us with a template as we seek to learn more about the Woodlands’ rich garden history.”

According to archaeologist Sarah Chesney, who identified and excavated the Woodlands’ greenhouse, the structure is an example of Hamilton’s fervor for this project. “You have to be committed to pour resources and time into what was really a non-essential building,” she says. “Its remains are now valuable physical evidence of this remarkable and transient exchange of plants and ideas.” After Hamilton’s death, the estate was eventually sold and the gardens gave way to a public cemetery in the 1840s. “We have a nineteenth-century cemetery superimposed on an eighteenth-century estate,” explains the Woodlands’ executive director Jessica Baumert. “The company used as much of the infrastructure that was already in place as they could to design the cemetery, and that will provide us with a template as we seek to learn more about the Woodlands’ rich garden history.”

Royal Gardens

By HYUNG-EUN KIM

Thursday, March 22, 2018

The front yard of a Korean home was traditionally left empty, while the backyard, which sometimes led to small nearby mountains, was cultivated as a garden. This held true for palace gardens as well. A pond and a pavilion from which to take in the surrounding landscape were considered vital elements. Such is the case at Hyangwonjeong in Gyeongbokgung Palace. Hyangwonjeong, which means “a pavilion from where scent spread,” was created between 1867 and 1873 on a small island constructed in the middle of a pond. Hyangwonjeong is currently being excavated by the Ganghwa National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. Archaeologists have found that the bridge that connects the pavilion to the land, at more than 100 feet, was the longest wooden bridge in its day. This bridge was destroyed during the Korean War and has now been reconstructed. Sadly, this is also near the spot where Queen Min (or Empress Myeongseong) was assassinated by the Japanese in 1895, one of the preludes to Japanese colonial rule of Korea.

Food and Wine Gardens

By JASON URBANUS

Thursday, March 22, 2018

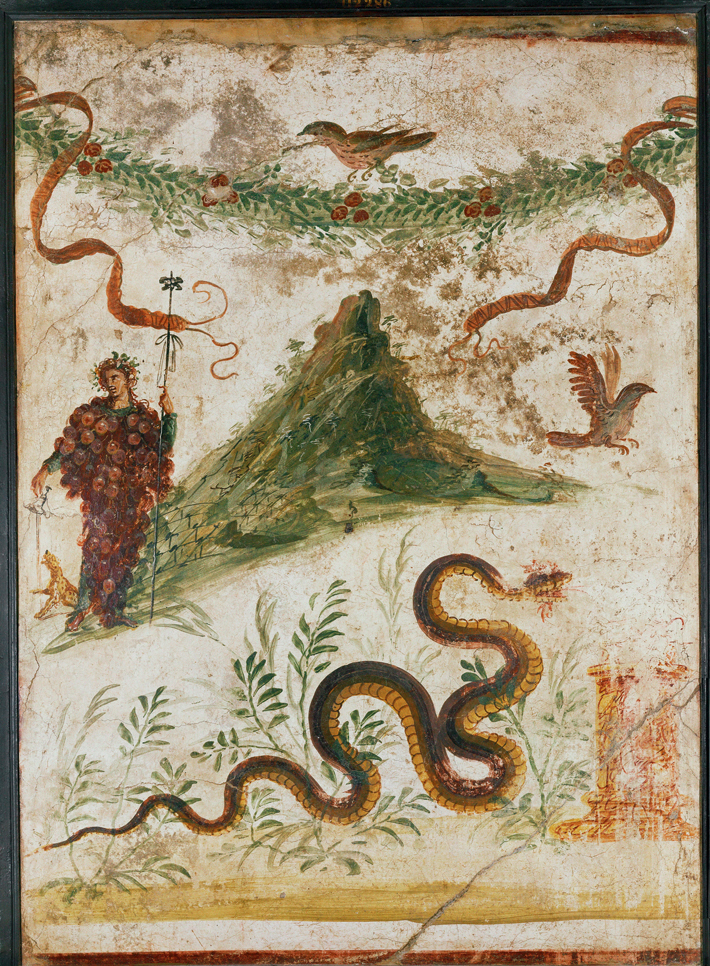

Evidence continues to reveal much about the quality of life of the residents of ancient Pompeii. The city created an intricate and robust system for the local production of food and wine. Researchers have long been aware of frescoes, found in many surviving houses and villas, depicting plants and the pleasure of eating and drinking. Remains of triclinia, or dining rooms, and of food stalls, bakeries, and shops selling the fish sauce garum are abundant.

Evidence continues to reveal much about the quality of life of the residents of ancient Pompeii. The city created an intricate and robust system for the local production of food and wine. Researchers have long been aware of frescoes, found in many surviving houses and villas, depicting plants and the pleasure of eating and drinking. Remains of triclinia, or dining rooms, and of food stalls, bakeries, and shops selling the fish sauce garum are abundant.

Garden archaeology as a discipline was pioneered in Pompeii in the 1950s when archaeologist Wilhelmina Jashemski began to excavate areas between the remaining structures. She discovered that homeowners planted flowers, dietary staples, and even small vineyards. “From the oldest type of domestic vegetable garden, the hortus, to ornate temple gardens,” explains Betty Jo Mayeske, director of the Pompeii Food and Wine Project, “you see evidence of cultivation in nearly every available space in Pompeii.” It appears that both grain and grapes were grown in small, local contexts. “There was a bakery on practically every single corner and the mills were there too, as well as a counter room and large ovens,” she says. “The whole production process took place there, and there are also several similar examples of small-scale vineyards.” One of Jashemski’s innovations was to apply the practice of making molds of the dead, known since the 1860s, to making molds of individual plants. “Casting had been done in cement and plaster on human remains for years,” Mayeske says, “but Jashemski used that technology to cast the plants’ roots, which helped definitively identify all of these gardens and vineyards.”

Garden archaeology as a discipline was pioneered in Pompeii in the 1950s when archaeologist Wilhelmina Jashemski began to excavate areas between the remaining structures. She discovered that homeowners planted flowers, dietary staples, and even small vineyards. “From the oldest type of domestic vegetable garden, the hortus, to ornate temple gardens,” explains Betty Jo Mayeske, director of the Pompeii Food and Wine Project, “you see evidence of cultivation in nearly every available space in Pompeii.” It appears that both grain and grapes were grown in small, local contexts. “There was a bakery on practically every single corner and the mills were there too, as well as a counter room and large ovens,” she says. “The whole production process took place there, and there are also several similar examples of small-scale vineyards.” One of Jashemski’s innovations was to apply the practice of making molds of the dead, known since the 1860s, to making molds of individual plants. “Casting had been done in cement and plaster on human remains for years,” Mayeske says, “but Jashemski used that technology to cast the plants’ roots, which helped definitively identify all of these gardens and vineyards.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement