From the Trenches

Satellites on the Silk Road

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, February 12, 2018

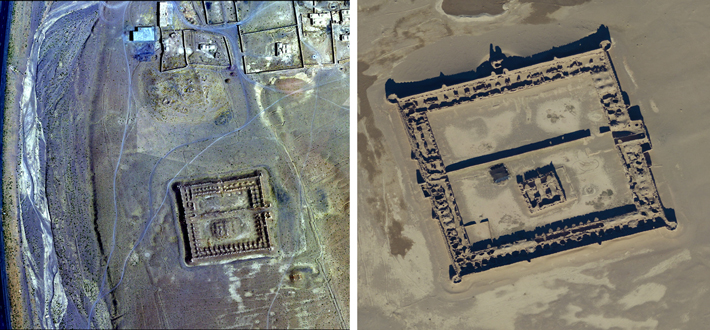

For thousands of years, Afghanistan has provided a passage for conquerors and commerce alike. It has also very often been a place of conflict. For decades, the U.S. Departments of Defense and State have had spy satellites collecting images over the country, some of which they are now sharing with researchers from the University of Chicago’s Afghan Heritage Mapping Project (AHMP). “The imagery is absolutely phenomenal,” says AHMP’s Kathryn Franklin. “Every single day in the lab someone says, ‘Do you see what I’m seeing?’ There’s something a little bit magic in it.”

Working with their Afghan colleagues, the AHMP’s goal is to record all of Afghanistan’s cultural features. One of the most recent stunning successes has been the identification of 160 large early modern caravanserais where travelers and traders would stop for the night as they and their camels made their way along the Silk Road carrying gems, spices, sugar, textiles, ceramics, paper, money, and slaves. Apart from their size and frequency, what makes the caravanserais so amazing, explains Franklin, is that the idea has persisted that as soon as people could use boats, they did so exclusively. “But now we have this overwhelming evidence,” she explains, “that these important routes were preserved and maintained by the Persian and Mughal Empires because trade and travel were important not just economically, but to their ideas of how to be a rich and powerful state.”

He’s No Stone Face

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, February 12, 2018

A recently rediscovered fragment of an abbot’s grave slab from North Wales may offer an unusual glimpse of a medieval personality. University of Chester archaeologist Howard Williams analyzed the two-foot-long stone piece and found that it once lay atop the tomb of an abbot named Howel who led an important Welsh abbey around 1300. Williams notes that the slab depicts Howel in realistic fashion—rare for the period—and wearing a broad smile. “It’s eerie,” says Williams. “The vast majority of these medieval funerary monuments show somber-looking characters who are focused on prayer, not grinning as if for a graduation portrait.” Williams notes that Howel was abbot during the English conquest of Wales in 1283, which left his abbey severely damaged. Records suggest Howel was a power broker during the period and might have been seen as an important source of stability in the community. Williams speculates that the monks who fashioned the slab may have been trying to capture Abbot Howel’s reassuring character. “That smile might have communicated that sense of ‘keep calm and carry on,’” says Williams. In troubled times, perhaps the fond memory of a smiling abbot offered some comfort to the monks he left behind.

The Mesopotamian Merchant Files

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, February 12, 2018

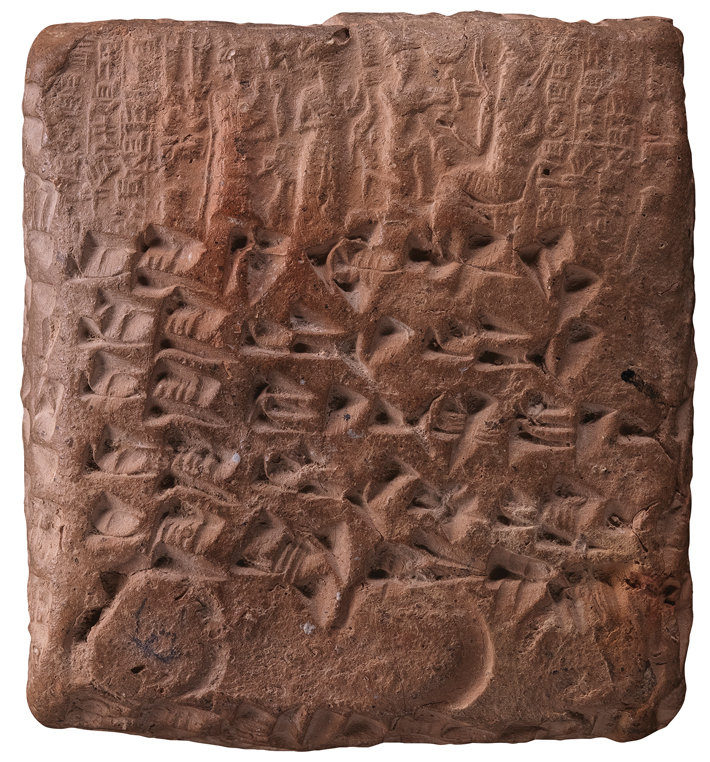

The world’s earliest evidence for a robust long-distance trading network comes in the form of thousands of clay tablets excavated from the Bronze Age site of Kanesh, in central Turkey. From about 2000 to 1750 B.C., this bustling city played host to a number of foreign merchants from Ashur, an Assyrian city some 700 miles to the southeast in modern-day Iraq. At the end of the third millennium B.C., Ashur’s king lifted the government monopoly on trade, opening the way for private merchants to operate donkey caravans that took luxury fabrics and tin north into the Anatolian heartland, where they exchanged their wares for silver and gold bullion in at least 27 city-states. In private archives at Kanesh, these entrepreneurs stored clay tablets inscribed with their business letters and contracts, as well as shipping and accounting records. A massive fire destroyed the merchants’ homes, but also baked and preserved these tablets, leaving a record of intensive trade whose detail wouldn’t be matched until the merchant houses of the Italian Renaissance began to document their activities.

Harvard University Assyriologist Gojko Barjamovic is currently collaborating with a group of economists, including the University of Virginia’s Kerem A. Cosar, to use mathematical models to analyze data from the tablets to reconstruct this vibrant trading system. Such is the fine-grained nature of these documents that the team has been able to use them to estimate the locations of 11 “lost” cities, ancient centers whose names are mentioned in the tablets but whose geographic position is unknown.

Barjamovic has long studied the Kanesh tablets and used traditional historical techniques to examine trade routes and posit the location of these lost cities. “I’ve traveled all over central Turkey to get to know the region,” says Barjamovic. “I’ve even stopped in towns and asked local old-timers where the trade routes were before modern roads were built.” Now, he has teamed up with Cosar and two other economists to analyze the tablets using quantitative techniques based on an economic concept known as the structural gravity model. First developed in the 1960s, the model, surprisingly, is based on Newton’s law of universal gravitation, which states that the mass and distance between two particles determines the gravitational attraction between them. This law was used in the mid-nineteenth century to predict the existence and location of Neptune based on anomalies observed in the orbit of Uranus. In a new application of the concept, modern-day economists use the structural gravity model to posit trade relationships between economic units based on their size and the distance between them. “It’s a very successful model,” says Cosar. “It can predict trade flows between cities or countries with an 80 percent success rate.”

Barjamovic has long studied the Kanesh tablets and used traditional historical techniques to examine trade routes and posit the location of these lost cities. “I’ve traveled all over central Turkey to get to know the region,” says Barjamovic. “I’ve even stopped in towns and asked local old-timers where the trade routes were before modern roads were built.” Now, he has teamed up with Cosar and two other economists to analyze the tablets using quantitative techniques based on an economic concept known as the structural gravity model. First developed in the 1960s, the model, surprisingly, is based on Newton’s law of universal gravitation, which states that the mass and distance between two particles determines the gravitational attraction between them. This law was used in the mid-nineteenth century to predict the existence and location of Neptune based on anomalies observed in the orbit of Uranus. In a new application of the concept, modern-day economists use the structural gravity model to posit trade relationships between economic units based on their size and the distance between them. “It’s a very successful model,” says Cosar. “It can predict trade flows between cities or countries with an 80 percent success rate.”

The team began by isolating 2,806 tablets that mentioned travel itineraries between two or more cities. They then employed equations based on the structural gravity model to predict trade flow between different centers. “We know where Kanesh and the other known cities are located,” says Cosar. “Depending on how much a lost city interacted with known cities, we could estimate the distance between those cities, as well as their economic size.” The model predicted locations of the lost cities within a radius of about 20 miles. In many cases, the team’s estimates lined up with proposals made by historians. In other cases, they supported one historian’s proposal over another. Remarkably, the ancient economic sizes of the cities could also be used to predict the income and population of cities now located in the same regions in modern-day Turkey. The key to a city’s long-term success, it seems, lies in its position on natural trade routes, ones first plied by donkey caravans some 4,000 years ago.

Off the Grid

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, February 12, 2018

El Pilar, an ancient Maya city that straddles the border between modern-day Belize and Guatemala, boasts more than 25 plazas and numerous houses, temples, and grand monumental structures. Archaeologist Anabel Ford, who first recorded the site in 1983, works with local Maya people, in cooperation with both governments, to run El Pilar Archaeological Reserve for Maya Flora and Fauna. Much as it may have been some 2,300 years ago when first settled, the city remains nestled in the forest, one with the natural environment. This distinguishes El Pilar from other, perhaps better-known, Maya sites throughout Mexico and Central America, where trees are often removed and lawns manicured to accommodate tourists.

El Pilar, a major urban center at its height between A.D. 500 and 1000, featured large forest gardens, relying on swidden, or slash-and-burn, agriculture. Ford has worked for decades with the native Maya community to preserve indigenous agricultural and gardening practices. At El Pilar, as a result, visitors can explore the remains of the ancient city by following nature trails leading them through plazas, and can discover Maya ruins as some of the first archaeologists to encounter them did in the nineteenth century. “This is how I would like the site to be viewed,” Ford says, “through the roots and the trees and vines, so you really feel like you’re coming upon it for the first time.”

THE SITE

THE SITE

While the reserve is accessible from Guatemala, most visitors will likely arrive from Belize. El Pilar can be reached from the village of Bullet Tree Falls, just outside the town of San Ignacio. A Belize Institute of Archaeology sign in Bullet Tree Falls marks an all-weather dirt road that leads to the site. Local tour companies offer excursions, and visitors can arrive by taxi, rental car, mountain bike, or horse, or they can hike the roughly seven-mile road. Guests are encouraged to explore on their own, but site caretakers and local tour guides are a helpful resource for any interested traveler.

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

Belize’s Cayo District is home to a wealth of Maya historical sites. Begin your journey at El Pilar in the morning when it is coolest and then travel back to San Ignacio to have lunch and visit the nearby Cahal Pech, believed to have been an acropolis-palace for an elite Maya family during the Classic period, between A.D. 250 and 900.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Mesopotamian Merchant Files

Off the Grid

He’s No Stone Face

Satellites on the Silk Road

Gods of the Galilee

The Venus of Vlakno

Caesar’s English Beachhead

Head in the Sand

Seals of Approval

Early Signs of Empire

Tut’s Mesopotamian Side

Newtonian Whiteboard

Nomadic Chic

Old Woman and the Sea

World Roundup

A rare Neolithic vintage, rock art on the Orinoco, Little Foot the Australopithecus, and medieval bishops’ bachelor pad

Artifact

The early sherd special

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement