From the Trenches

Spheres of Influence

By MARLEY BROWN

Tuesday, August 07, 2018

Intricately carved stone balls of unknown purpose, which date to the third millennium B.C. and have been discovered throughout the British Isles—though most frequently in northeast Scotland—continue to beguile scholars. National Museums Scotland houses the greatest number of these objects, and has recently built interactive 3-D models of several using photogrammetry. “In some cases details not apparent to the naked eye are revealed,” explains Hugo Anderson-Whymark, the National Museums Scotland curator who created the models. “For example, on one ball I identified fine concentric circles that have never been observed before.” Several theories have been put forward over the years about what the balls were for, though Anderson-Whymark believes that those postulating use in battle or in ritual contexts are among the most plausible. “For at least some of these artifacts,” Anderson-Whymark observes, “it’s likely they were deployed as symbolic or ceremonial weapons that indicated the status and authority of their holder.” To see 3-D models of many of these artifacts, click here.

Intricately carved stone balls of unknown purpose, which date to the third millennium B.C. and have been discovered throughout the British Isles—though most frequently in northeast Scotland—continue to beguile scholars. National Museums Scotland houses the greatest number of these objects, and has recently built interactive 3-D models of several using photogrammetry. “In some cases details not apparent to the naked eye are revealed,” explains Hugo Anderson-Whymark, the National Museums Scotland curator who created the models. “For example, on one ball I identified fine concentric circles that have never been observed before.” Several theories have been put forward over the years about what the balls were for, though Anderson-Whymark believes that those postulating use in battle or in ritual contexts are among the most plausible. “For at least some of these artifacts,” Anderson-Whymark observes, “it’s likely they were deployed as symbolic or ceremonial weapons that indicated the status and authority of their holder.” To see 3-D models of many of these artifacts, click here.

All Bundled Up

By MARLEY BROWN

Tuesday, August 07, 2018

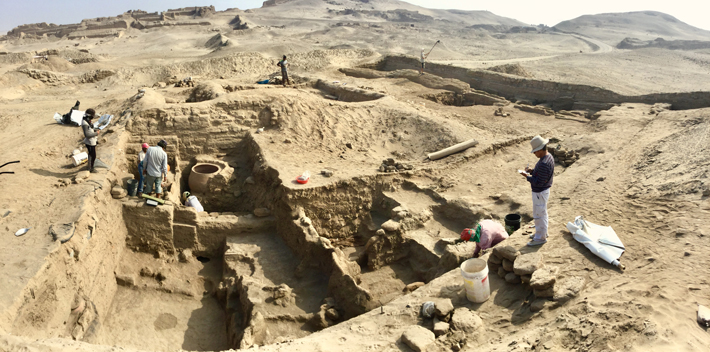

Archaeologists working at Pachacamac, a pre-Columbian pilgrimage site and ceremonial center on the coast of Peru, have uncovered a well-preserved mummy buried sometime between A.D. 1000 and 1200. The team discovered the mummy while excavating remains of a structure once devoted to local ancestors. The building appears to have been transformed into a ritual healing facility when the Inca Empire absorbed Pachacamac in the late fifteenth century. “We knew there was an important cemetery beneath the building, which had been continually looted since the Spanish conquest in 1533,” says Peter Eeckhout of the Université libre de Bruxelles, who has directed excavations at the site since 1999. “Finding the burial in such a perfect state is miraculous.” Researchers will soon examine the mummy using medical imaging and 3-D reconstruction technology to determine the individual’s position within the bundle, detect possible diseases or injuries, and discover any grave goods included with the remains.

Archaeologists working at Pachacamac, a pre-Columbian pilgrimage site and ceremonial center on the coast of Peru, have uncovered a well-preserved mummy buried sometime between A.D. 1000 and 1200. The team discovered the mummy while excavating remains of a structure once devoted to local ancestors. The building appears to have been transformed into a ritual healing facility when the Inca Empire absorbed Pachacamac in the late fifteenth century. “We knew there was an important cemetery beneath the building, which had been continually looted since the Spanish conquest in 1533,” says Peter Eeckhout of the Université libre de Bruxelles, who has directed excavations at the site since 1999. “Finding the burial in such a perfect state is miraculous.” Researchers will soon examine the mummy using medical imaging and 3-D reconstruction technology to determine the individual’s position within the bundle, detect possible diseases or injuries, and discover any grave goods included with the remains.

Off the Grid

By MARLEY BROWN

Tuesday, August 07, 2018

A two-mile-long dirt road through Benin’s coastal town of Ouidah leads to the Door of No Return, a monument to some one million enslaved people forced there onto boats bound for European colonies in North America, South America, and the Caribbean. It runs the short distance from the market square, where slaves were sold, to the Atlantic Ocean, where the Middle Passage began. When Europeans first arrived in the late fifteenth century, Ouidah—then known as Gléwé—was the port of the local Hueda Kingdom, which gives the modern town its name. Early explorers and missionaries were soon joined by traders, who established forts and began purchasing slaves from Hueda rulers. By the end of the seventeenth century, some 10,000 enslaved individuals left Ouidah every year. The town was one of the busiest hubs in the maritime world. Ouidah also became a nexus for goods and cultural practices from Europe all the way to the Indian Ocean. This mélange of influences grew into new traditions, too, such as syncretic forms of Vodun, or Voodoo, of which Ouidah remains a major center. The neighboring Dahomey Kingdom invaded in 1727 and, apart from a period of French colonial rule in the twentieth century, the town has remained part of Dahomey, now the Republic of Benin. Ouidah today is not only a pilgrimage site for devotees of Vodun and a powerful memorial to Africans taken from their homelands, but also a celebration of diaspora communities formed by their descendants around the world.

A two-mile-long dirt road through Benin’s coastal town of Ouidah leads to the Door of No Return, a monument to some one million enslaved people forced there onto boats bound for European colonies in North America, South America, and the Caribbean. It runs the short distance from the market square, where slaves were sold, to the Atlantic Ocean, where the Middle Passage began. When Europeans first arrived in the late fifteenth century, Ouidah—then known as Gléwé—was the port of the local Hueda Kingdom, which gives the modern town its name. Early explorers and missionaries were soon joined by traders, who established forts and began purchasing slaves from Hueda rulers. By the end of the seventeenth century, some 10,000 enslaved individuals left Ouidah every year. The town was one of the busiest hubs in the maritime world. Ouidah also became a nexus for goods and cultural practices from Europe all the way to the Indian Ocean. This mélange of influences grew into new traditions, too, such as syncretic forms of Vodun, or Voodoo, of which Ouidah remains a major center. The neighboring Dahomey Kingdom invaded in 1727 and, apart from a period of French colonial rule in the twentieth century, the town has remained part of Dahomey, now the Republic of Benin. Ouidah today is not only a pilgrimage site for devotees of Vodun and a powerful memorial to Africans taken from their homelands, but also a celebration of diaspora communities formed by their descendants around the world.

THE SITE

THE SITE

Begin at the Ouidah Museum of History, housed in a Portuguese fort built in 1721. Exhibits interpret the lives of Huedans before European arrival, provide an overview of the transatlantic slave trade, and display archaeological artifacts recovered in the area. Visitors should then walk or take a taxi to the Sacred Forest of Kpassè Zoun, a park devoted to Vodun deities said to contain the remains of King Kpassè, founder of Ouidah. End your tour at the Door of No Return on Ouidah Beach, where large middens full of broken clay pipes, wine bottles, and ceramics abandoned by traders can still be seen. “The middens might be the most poignant reminders of the slave trade visible in Ouidah,” says Neil Norman, an archaeologist at the College of William and Mary who has conducted extensive excavations in the area. “They represent just a tiny fraction of material that was imported so human beings could go the other way.”

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

Hire a car to take you 45 minutes down the coast to the region’s big city, Cotonou, which also is a good place to stay. While there, explore the Dantokpa Market, which is said to be the largest open-air market in West Africa. You can then hit the beach or visit the Fondation Zinsou, a museum and cultural foundation established in 2005 that specializes in contemporary African art.

Hellenistic Helmet Safety

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, August 07, 2018

Archaeologists have discovered a bronze Corinthian helmet in the burial of several fifth-century B.C. Greek warriors in southwestern Russia. This type of helmet, which completely covers the head and neck, is depicted on iconic statues of such figures as the Athenian statesman Pericles and the goddess Athena, but is rarely found during modern excavations. The recently unearthed example was uncovered at a necropolis on the Taman Peninsula, which, together with parts of Crimea, formed the territory of the Bosporan Kingdom, a Greek state that was founded around 480 B.C.

Archaeologists have discovered a bronze Corinthian helmet in the burial of several fifth-century B.C. Greek warriors in southwestern Russia. This type of helmet, which completely covers the head and neck, is depicted on iconic statues of such figures as the Athenian statesman Pericles and the goddess Athena, but is rarely found during modern excavations. The recently unearthed example was uncovered at a necropolis on the Taman Peninsula, which, together with parts of Crimea, formed the territory of the Bosporan Kingdom, a Greek state that was founded around 480 B.C.

In addition to the helmet, the burial also included the men’s weapons, as well as an amphora and other ceramics. Bridled horses were interred nearby, suggesting that the warriors may have been cavalrymen. Roman Mimokhod of the Russian Academy of Sciences, who leads the excavations at the site, speculates that the warriors all fell during the same battle, perhaps during a conflict with one of the nearby nomadic tribes. But the men’s lives were evidently not completely consumed by warfare. Mimokhod’s team found that one of the warriors was buried with his harp.

In addition to the helmet, the burial also included the men’s weapons, as well as an amphora and other ceramics. Bridled horses were interred nearby, suggesting that the warriors may have been cavalrymen. Roman Mimokhod of the Russian Academy of Sciences, who leads the excavations at the site, speculates that the warriors all fell during the same battle, perhaps during a conflict with one of the nearby nomadic tribes. But the men’s lives were evidently not completely consumed by warfare. Mimokhod’s team found that one of the warriors was buried with his harp.

Ice Age Necropolis

By LYDIA PYNE

Tuesday, August 07, 2018

In the Upper Paleolithic period, just over 12,000 years ago, Arene Candide in Italy’s northwestern Liguria region was an imposing cave with a massive, nearly 300-foot sand dune next to its entrance. Today, the dune has been quarried away. For archaeologist Vitale Sparacello of the University of Bordeaux, Arene Candide is key to understanding humanity’s legacy in the region. Sparacello grew up in Genoa, just about an hour east of Arene Candide, and has long been fascinated by the deep history the region has to offer. Unlike other caves, which have been studied mostly to see how people lived in them, for Sparacello and his colleagues, the site provides something else altogether—insight into how Paleolithic people buried their dead.

In the Upper Paleolithic period, just over 12,000 years ago, Arene Candide in Italy’s northwestern Liguria region was an imposing cave with a massive, nearly 300-foot sand dune next to its entrance. Today, the dune has been quarried away. For archaeologist Vitale Sparacello of the University of Bordeaux, Arene Candide is key to understanding humanity’s legacy in the region. Sparacello grew up in Genoa, just about an hour east of Arene Candide, and has long been fascinated by the deep history the region has to offer. Unlike other caves, which have been studied mostly to see how people lived in them, for Sparacello and his colleagues, the site provides something else altogether—insight into how Paleolithic people buried their dead.

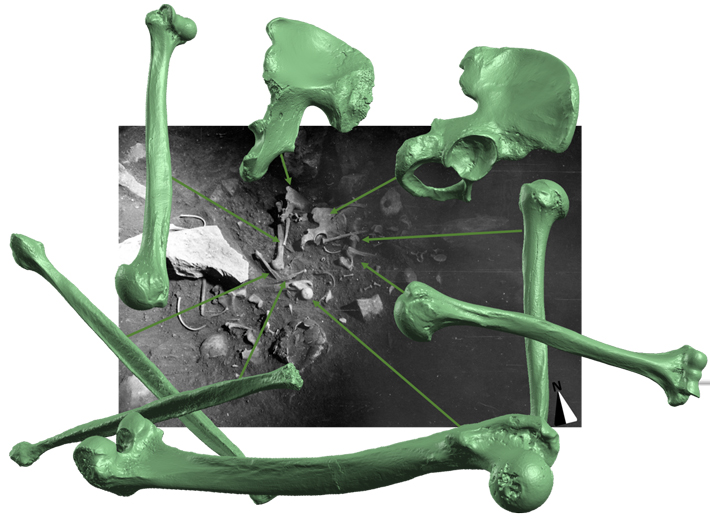

Arene Candide has 10 primary Paleolithic burials, two of which are double burials, and seven clusters of bones, totaling at least 20 individuals. There is a single burial, some 10,000 years older at the site, nicknamed the “young prince.” Piecing together the story of Arene Candide has not been easy. Working with the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage in Liguria, the Ligurian Archaeological Museum, the Archaeological Museum of Finale, and the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Florence, Sparacello combed through both the collections of human remains removed from the cave and the museums’ archives, in addition to participating in fieldwork at the site over several years, to illuminate what happened at the site during the Upper Paleolithic. “You always wish earlier excavations had done more, taken more notes, more photographs,” Sparacello says. “But it is humbling to see how much good work they did, especially when you go back to the field and realize that you are responsible for documenting your own generation’s excavations.”

The upper, most recent, levels of Arene Candide were first excavated in the 1880s and were found to contain several Neolithic burials dating to 5000–4300 B.C. Six decades later, in the 1940s, archaeologists dug through the site’s middle layers and uncovered the Paleolithic individuals, dating to more than 12,000 years ago. They were interred beneath a thick rocky layer in the cave that separated the older from the younger strata. These researchers described Arene Candide as a necropolis, based on the plethora of Neolithic burials. More recently, Sparacello and his colleagues have been able to take that description even further, concluding that Arene Candide was a place that Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers visited time and time again in order to inter their dead. They did this for more than 500 years, nearly 20 generations.

Sparacello’s research suggests that some of Arene Candide’s burials were intentionally moved from their original context. This happened in two distinct phases, separated by only a few centuries (10,820–10,420 B.C. and 10,030–9180 B.C.) But the older burials were not just haphazardly moved aside to make room for new bodies—the bones from the earlier burials were incorporated into the newer ones. Crania and other skeletal elements from the older burials were also integrated into the arrangement of stones that encircled the more recent examples.

Sparacello’s research suggests that some of Arene Candide’s burials were intentionally moved from their original context. This happened in two distinct phases, separated by only a few centuries (10,820–10,420 B.C. and 10,030–9180 B.C.) But the older burials were not just haphazardly moved aside to make room for new bodies—the bones from the earlier burials were incorporated into the newer ones. Crania and other skeletal elements from the older burials were also integrated into the arrangement of stones that encircled the more recent examples.

Moreover, two individuals from different periods share skeletal anomalies, possibly related to congenital rickets. “This does not appear to be a coincidence,” Sparacello says. “People performing this funerary behavior knew whose bones were involved. We suggest that shared pathologies, especially congenital, may have been the focus of Paleolithic funerary behavior, particularly when it involved multiple individuals.” In addition, small, broken stones were found near the burial circles. Attempts to rejoin the halves of the pebbles have not been successful, leading researchers to propose that half a pebble was left with the dead while the other half was carried away as a talisman or souvenir.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Ice Age Necropolis

Off the Grid

Hellenistic Helmet Safety

All Bundled Up

Spheres of Influence

Hand Picked

Ancient Foresters

Indian Warrior Class

Please Wash Your Hands

Can You Dig It, Man?

Breaking the Mold

A Very Long Way to Eat Rhino

Hold Your Horses

Making an Entrance

Do No Harm

World Roundup

Ancient Japanese peach pits, the weight of Maya prestige, kangaroo cookout, early American smokers, and a lost Illyrian city

Artifact

Not just a pretty base

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement