From the Trenches

Mars Explored

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, October 15, 2018

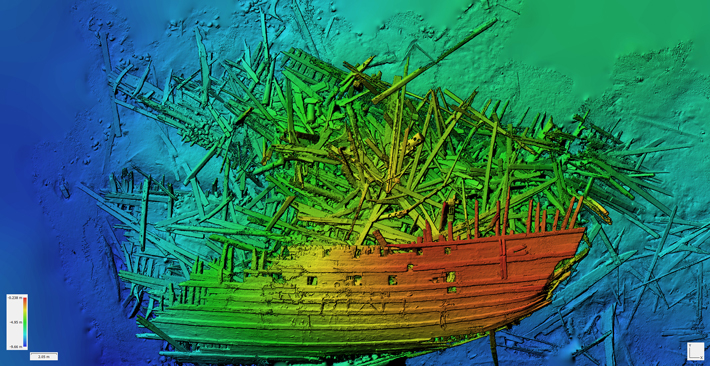

The wreckage of Mars, a sixteenth-century Swedish warship that lies 230 feet under the Baltic Sea near the island of Öland, has yielded evidence of the dramatic events that led to its sinking. History records that in 1564, during the Northern Seven Years’ War, several hundred soldiers from Danish and Lübeckian warships boarded Mars and subdued its crew. Then, according to contemporary sources, Mars’ main gunpowder hold exploded, killing most of those on board. “We can see from the remains we have identified that there was a massive fire and the bow of the ship had just been blown off,” says maritime archaeologist Rolf Fabricius Warming. “We found it about 130 feet away from the rest of the ship.”

The wreckage of Mars, a sixteenth-century Swedish warship that lies 230 feet under the Baltic Sea near the island of Öland, has yielded evidence of the dramatic events that led to its sinking. History records that in 1564, during the Northern Seven Years’ War, several hundred soldiers from Danish and Lübeckian warships boarded Mars and subdued its crew. Then, according to contemporary sources, Mars’ main gunpowder hold exploded, killing most of those on board. “We can see from the remains we have identified that there was a massive fire and the bow of the ship had just been blown off,” says maritime archaeologist Rolf Fabricius Warming. “We found it about 130 feet away from the rest of the ship.”

Amid the wreckage, investigators have uncovered hand grenades and what are likely to be pieces of armor and a sword. They have also found skeletal parts, including a femur that was apparently damaged at the knee by a sharpedged weapon. A large grapnel, which may have been used by one of the attacking ships to grasp Mars before boarding, has turned up as well. The project has been carried out by the Maritime Archaeological Research Institute at Södertörn University in Sweden, Global Underwater Explorers, Västerviks Museum, Ocean Discovery, and the marine surveying firm MMT.

Amid the wreckage, investigators have uncovered hand grenades and what are likely to be pieces of armor and a sword. They have also found skeletal parts, including a femur that was apparently damaged at the knee by a sharpedged weapon. A large grapnel, which may have been used by one of the attacking ships to grasp Mars before boarding, has turned up as well. The project has been carried out by the Maritime Archaeological Research Institute at Södertörn University in Sweden, Global Underwater Explorers, Västerviks Museum, Ocean Discovery, and the marine surveying firm MMT.

Off the Grid

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, October 15, 2018

Thingvellir National Park, just under 30 miles northeast of Reykjavik, may accurately be described as the birthplace of the Icelandic nation. Situated on a boundary of tectonic plates, the 35-square-mile park is a patchwork of highlands, fertile fields, and rifts filled with crystal-clear water. Thingvellir translates to “plains of assembly.” The site was home to the Althing, Iceland’s parliament, which was founded as an open-air assembly in A.D. 930 and met there annually until 1798. The governing body was founded by some of the island’s first Viking settlers and turned into the pop-up capital of Iceland for two weeks every year. In addition to hosting legislative debate, the assembly featured markets, sporting competitions, and feasts. Local chieftains are believed to have sent an emissary to Norway to record laws with which to govern the newly colonized island. Upon his return, the lands of Thingvellir—seized from their owner when he was convicted of murder—were chosen as the place of assembly thanks to their central location and ample natural resources. Researchers have been at work for more than two decades surveying the entire park for sites of archaeological significance. Among these are the remains of the Althing itself, including the ceremonial Lögberg, or “law rock,” a lithic outcrop where speeches and arguments were made, as well as remnants of turf-and-stone booths where high-status attendees set up camp. “Thingvellir was at the heart of all the major developments in Iceland’s history through the eighteenth century,” says archaeologist Margrét Hrönn Hallmundsdóttir, who has directed recent surveys. “While the site features prominently in the Icelandic sagas, especially with regard to feuds that were either resolved or not during the assembly, we continue to find archaeological remains we had no information about.”

Thingvellir National Park, just under 30 miles northeast of Reykjavik, may accurately be described as the birthplace of the Icelandic nation. Situated on a boundary of tectonic plates, the 35-square-mile park is a patchwork of highlands, fertile fields, and rifts filled with crystal-clear water. Thingvellir translates to “plains of assembly.” The site was home to the Althing, Iceland’s parliament, which was founded as an open-air assembly in A.D. 930 and met there annually until 1798. The governing body was founded by some of the island’s first Viking settlers and turned into the pop-up capital of Iceland for two weeks every year. In addition to hosting legislative debate, the assembly featured markets, sporting competitions, and feasts. Local chieftains are believed to have sent an emissary to Norway to record laws with which to govern the newly colonized island. Upon his return, the lands of Thingvellir—seized from their owner when he was convicted of murder—were chosen as the place of assembly thanks to their central location and ample natural resources. Researchers have been at work for more than two decades surveying the entire park for sites of archaeological significance. Among these are the remains of the Althing itself, including the ceremonial Lögberg, or “law rock,” a lithic outcrop where speeches and arguments were made, as well as remnants of turf-and-stone booths where high-status attendees set up camp. “Thingvellir was at the heart of all the major developments in Iceland’s history through the eighteenth century,” says archaeologist Margrét Hrönn Hallmundsdóttir, who has directed recent surveys. “While the site features prominently in the Icelandic sagas, especially with regard to feuds that were either resolved or not during the assembly, we continue to find archaeological remains we had no information about.”

THE SITE

THE SITE

Thingvellir is easily accessible via main roads from Reykjavik. Begin your tour at the visitor’s center, which provides an overview of activities available at the park, and features a new exhibit, just opened in 2018, on the history of the site. Then walk up to a viewing platform to take in the entirety of the main assembly area. Many of the archaeological points of interest in the park, including booth remnants and ancient runes still visible to the naked eye, are well-mapped and connected via footpaths. Agriculture buffs can also learn about the evolution of farming in Iceland from the ninth century through the Industrial Revolution and visit historic farm buildings. For guests who wish to stay overnight at the park, two campsites are maintained, along with a service center and cafeteria.

WHILE YOU’RE THERE

Do as the locals do and embrace all things outdoors. Park guests can hike, arrange horseback rides, snorkel in the park’s famed fissures, or, with luck during colder months, take in the northern lights. Having immersed yourself in the wildness of it all, return to Reykjavik to visit the National Museum of Iceland and the Reykjavik Maritime Museum. Visitors can only come away with newfound perspective on the ingenuity and determination of Iceland’s earliest settlers.

The American Canine Family Tree

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, October 15, 2018

The fate of the indigenous dogs of the New World in the wake of European colonization has long fascinated both scholars and dog lovers. Some modern breeds, such as Catahoulas and Mexican and Peruvian hairless, are popularly thought to trace their roots to ancestors who were present before Columbus’ arrival. In recent years, geneticists have looked into how much ancient DNA these and other breeds actually carry. Now, a widely reported, large-scale study by an international multidisciplinary team suggests that they do not have much—if any—indigenous American ancestry. According to this analysis, modern American dogs are almost entirely descended from European dogs that began arriving 500 years ago. “The indigenous American dogs seem to have been almost completely wiped out,” says Angela Perri, a zooarchaeologist from Durham University in England who participated in the study. This new finding contradicts other genetic studies that suggest some dogs living today still carry some indigenous DNA.

The fate of the indigenous dogs of the New World in the wake of European colonization has long fascinated both scholars and dog lovers. Some modern breeds, such as Catahoulas and Mexican and Peruvian hairless, are popularly thought to trace their roots to ancestors who were present before Columbus’ arrival. In recent years, geneticists have looked into how much ancient DNA these and other breeds actually carry. Now, a widely reported, large-scale study by an international multidisciplinary team suggests that they do not have much—if any—indigenous American ancestry. According to this analysis, modern American dogs are almost entirely descended from European dogs that began arriving 500 years ago. “The indigenous American dogs seem to have been almost completely wiped out,” says Angela Perri, a zooarchaeologist from Durham University in England who participated in the study. This new finding contradicts other genetic studies that suggest some dogs living today still carry some indigenous DNA.

Perri and her colleagues analyzed complete genomes retrieved from the remains of seven ancient dogs that lived in Siberia and North America, and those of more than 5,000 modern dogs. They also studied 71 samples of ancient dog mitochondrial DNA. Mitochondria are the organs that create energy inside living cells. They have their own genomes that are inherited from the mother’s side. The team’s analysis suggests that dogs were brought to the Americas in four migrations. The first dogs would have arrived from Asia 9,900 years ago, several thousand years after the first humans arrived. A second group of dogs may have been brought to the Arctic by the Thule people, the ancestors of the Inuit, about 1,000 years ago. The third migration began with the settlement of European colonies 500 years ago, and the last took place around 1900 when huskies were brought to Alaska from Siberia during the Gold Rush. Those last two migrations, the team believes, led to the almost total disappearance of the Americas’ indigenous dogs.

There may have been many reasons for this, says Perri. “Things like canine distemper or rabies came in with European dogs and may have taken a toll on native dog populations,” she says. Perri also cites historical documents describing Spanish explorers eating native dogs and notes that English colonists killed native dogs freely and prevented them from breeding with European dogs.

There may have been many reasons for this, says Perri. “Things like canine distemper or rabies came in with European dogs and may have taken a toll on native dog populations,” she says. Perri also cites historical documents describing Spanish explorers eating native dogs and notes that English colonists killed native dogs freely and prevented them from breeding with European dogs.

Another recent study of American dog DNA was led by Peter Savolainen, an evolutionary geneticist at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. His team examined mitochondrial DNA in some 2,000 modern dogs, and while they found evidence for large-scale replacement of indigenous dogs, they also detected traces of ancient DNA in the modern samples. “There is still a small percentage of ancient American ancestry in modern American dogs,” says Savolainen. His team’s analysis showed that Chihuahuas are related to Mexico’s indigenous dogs and that a free-ranging breed from the southeastern United States called the Carolina Dog has about 30 percent American ancestry. In Inuit dogs they did not find any European ancestry.

There are several factors that might account for the discrepancy between the teams’ findings. Savolainen acknowledges that his study would only have detected ancestry from female dogs since he did not examine complete genomes, as Perri’s team did. This could have skewed results. Perri, in addition, notes that it’s possible that Savolainen’s team did not distinguish between modern Arctic dog ancestry and precontact dog ancestry, because both carry similar types of mitochondrial DNA. Still, Perri acknowledges that her team’s study couldn’t sample DNA from every dog population in the Americas. “It’s likely,” she says, “that there are isolated populations in South and Central America that are descendants of the precontact group of dogs.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The American Canine Family Tree

Off the Grid

Mars Explored

Aztec Fishing

Iron Age Teenagers

Hand of God

Beauty Endures

Let Them Eat Soup

Another Form of Slavery

Eat More Spore

Well, Well

Nomadic Necropolis

Conan's Storm Cellar

World Roundup

Aztec rain temple, Ötzi’s last meal, Roman whalers, and Germany’s oldest public library

Artifact

A draft of comfort

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement